buy artwork

buy artwork

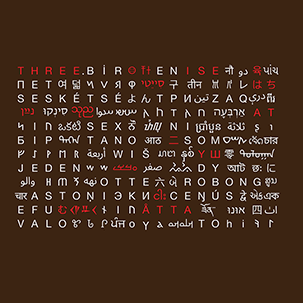

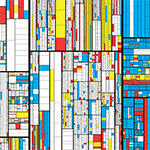

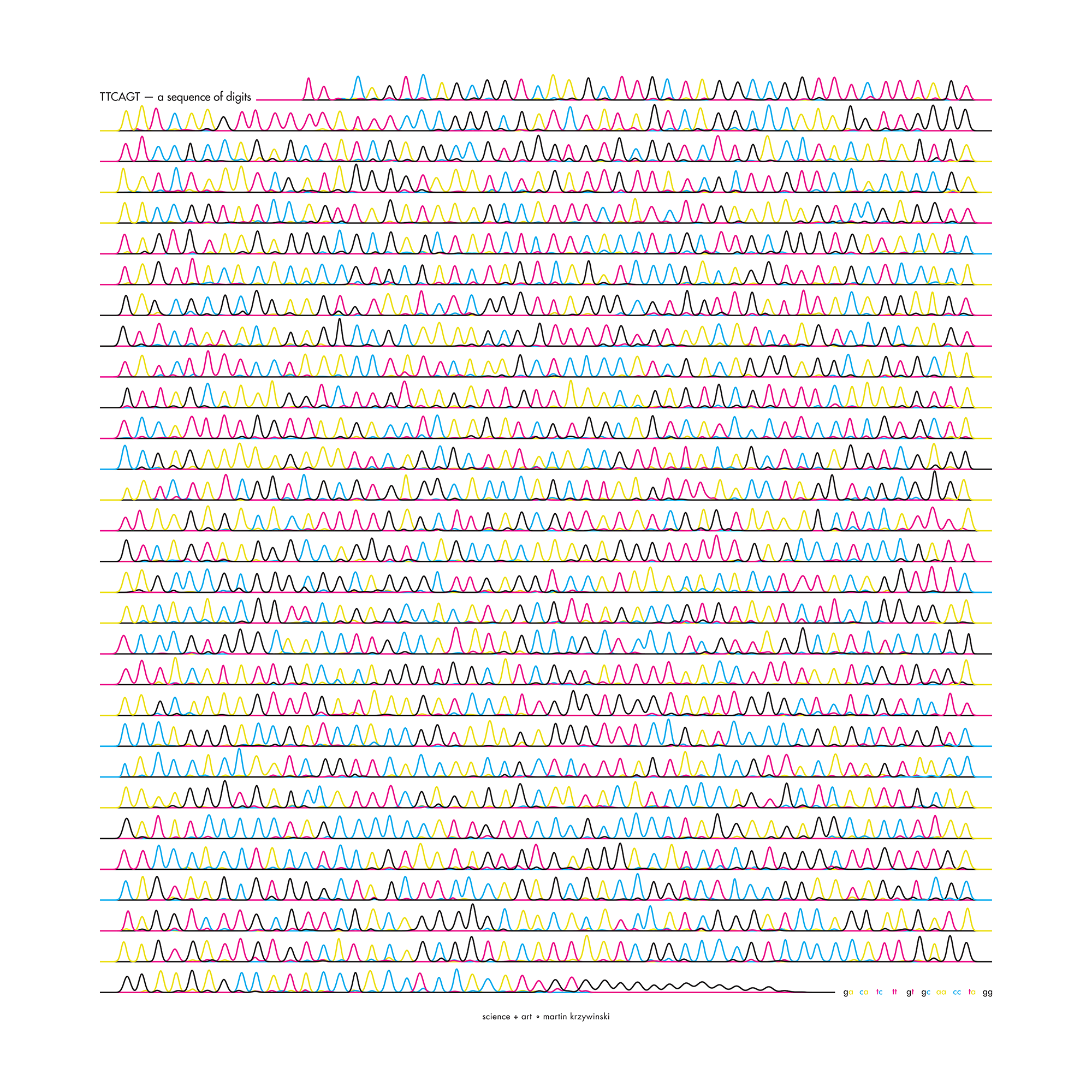

π Day 2025 Art Posters - TTCAGT: a sequence of digits

On March 14th celebrate `\pi` Day. Hug `\pi`—find a way to do it.

For those who favour `\tau=2\pi` will have to postpone celebrations until July 26th. That's what you get for thinking that `\pi` is wrong. I sympathize with this position and have `\tau` day art too!

If you're not into details, you may opt to party on July 22nd, which is `\pi` approximation day (`\pi` ≈ 22/7). It's 20% more accurate that the official `\pi` day!

Finally, if you believe that `\pi = 3`, you should read why `\pi` is not equal to 3.

Well—well; the sad minutes are moving,

Though loaded with trouble and pain;

And some time the loved and the loving

Shall meet on the mountains again!

—Emily Bronte

Welcome to this year's celebration of `\pi` and mathematics.

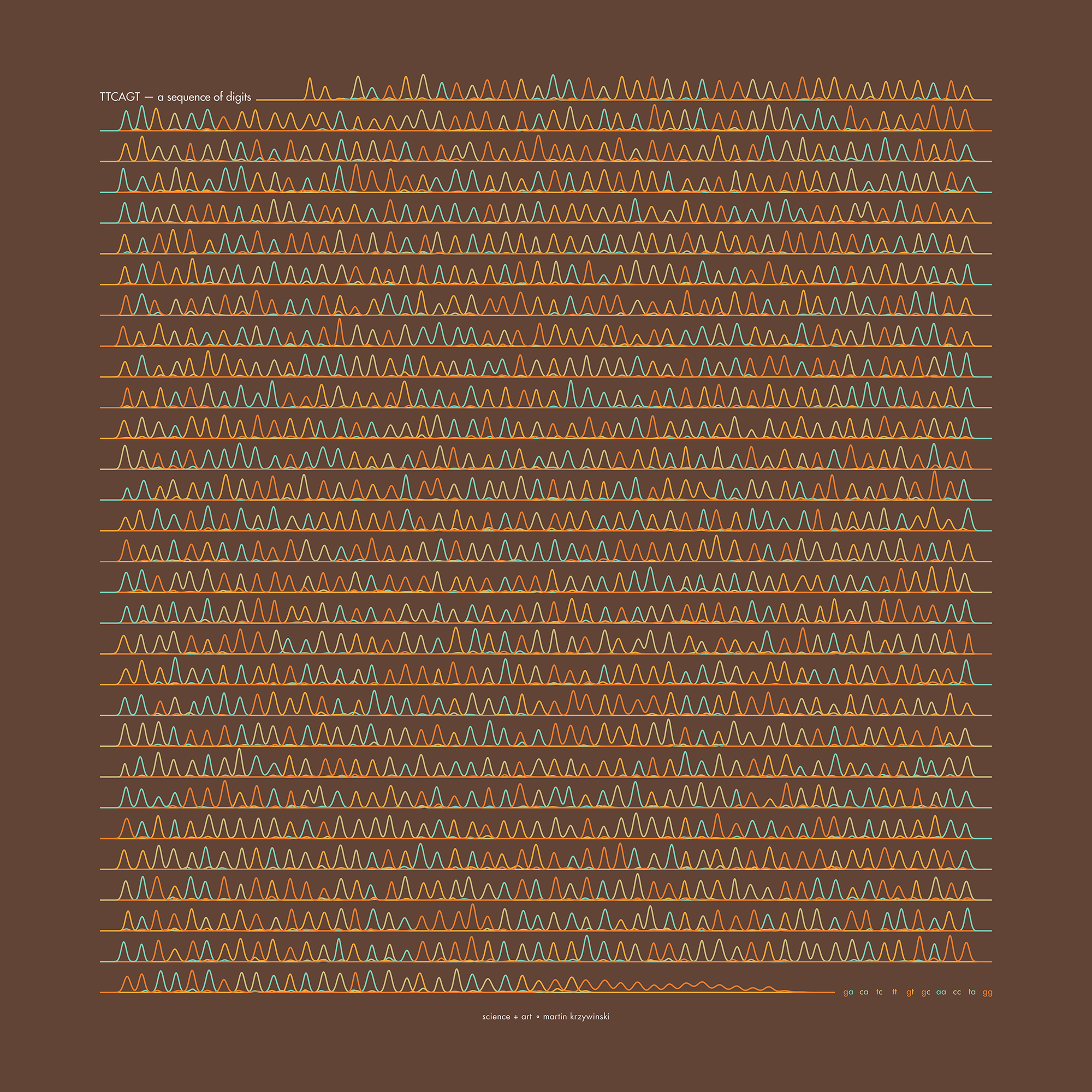

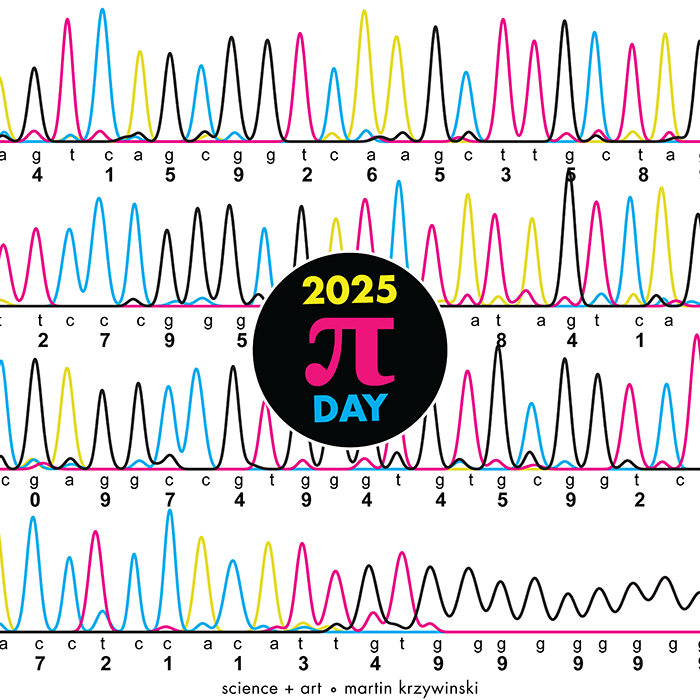

The theme this year is Sanger sequencing — old-school, one base at a time.

This year's `\pi` poem is Loud Without The Wind Was Roaring by Emily Bronte.

This year's `\pi` day song is Movements by Luca Musto.

Also, the tabbed menu above is full. Gasp.

I work in a genome center, so it was just a matter of time before one of the Pi Day celebrations encoded the digits of `\pi` as a sequence of nucleotides (A, T, G and C). It took 12 years.

Our first sequencer was the MegaBACE 1000, which now exists only in old photos).

Unfortunately, there was nothing "mega" about it. You were lucky to sequence 500 contiguous bases of DNA. So, halfakiloBACE?

Under the hood, the sequencing was done with the Sanger method.

Check out the method section to learn how Sanger sequencing works.

But briefly, it's a sequencing method in which bases are identified from a series of fluorescence peaks. This is why the art has peaks!

The posters show `\pi` up to the Feynman Point, which are six 9's at decimal places 762–767.

Each digit is encoded by two bases:

0 GA 1 CA 2 TC 3 TT 4 GT 5 GC 6 AA 7 CC 8 TA 9 GG

With this scheme, 3.14 reads as TTCAGT. Hence, the title of the art “TTCAGT: a sequence of digits.”

Explore the art posters.

buy artwork

buy artwork

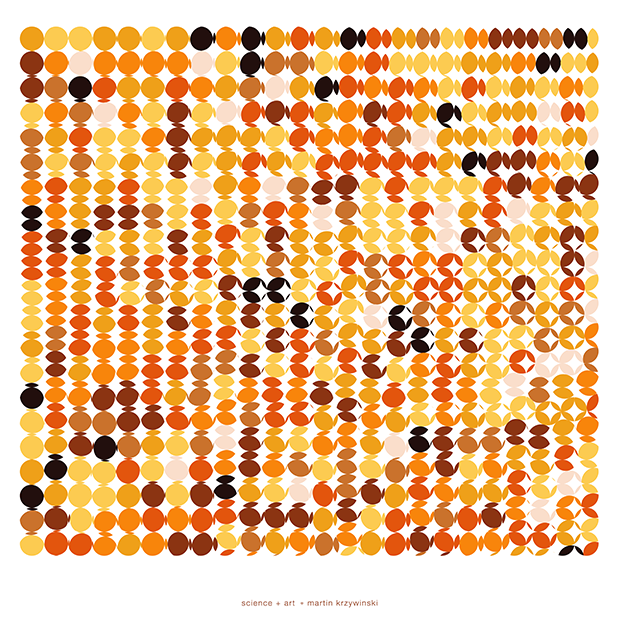

Beyond Belief Campaign BRCA Art

Fuelled by philanthropy, findings into the workings of BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes have led to groundbreaking research and lifesaving innovations to care for families facing cancer.

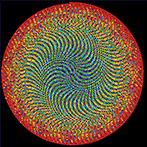

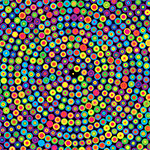

This set of 100 one-of-a-kind prints explore the structure of these genes. Each artwork is unique — if you put them all together, you get the full sequence of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 proteins.

Propensity score weighting

The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few. —Mr. Spock (Star Trek II)

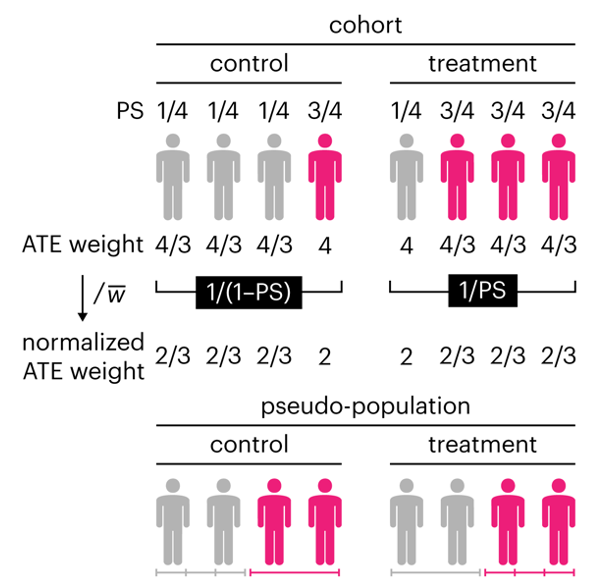

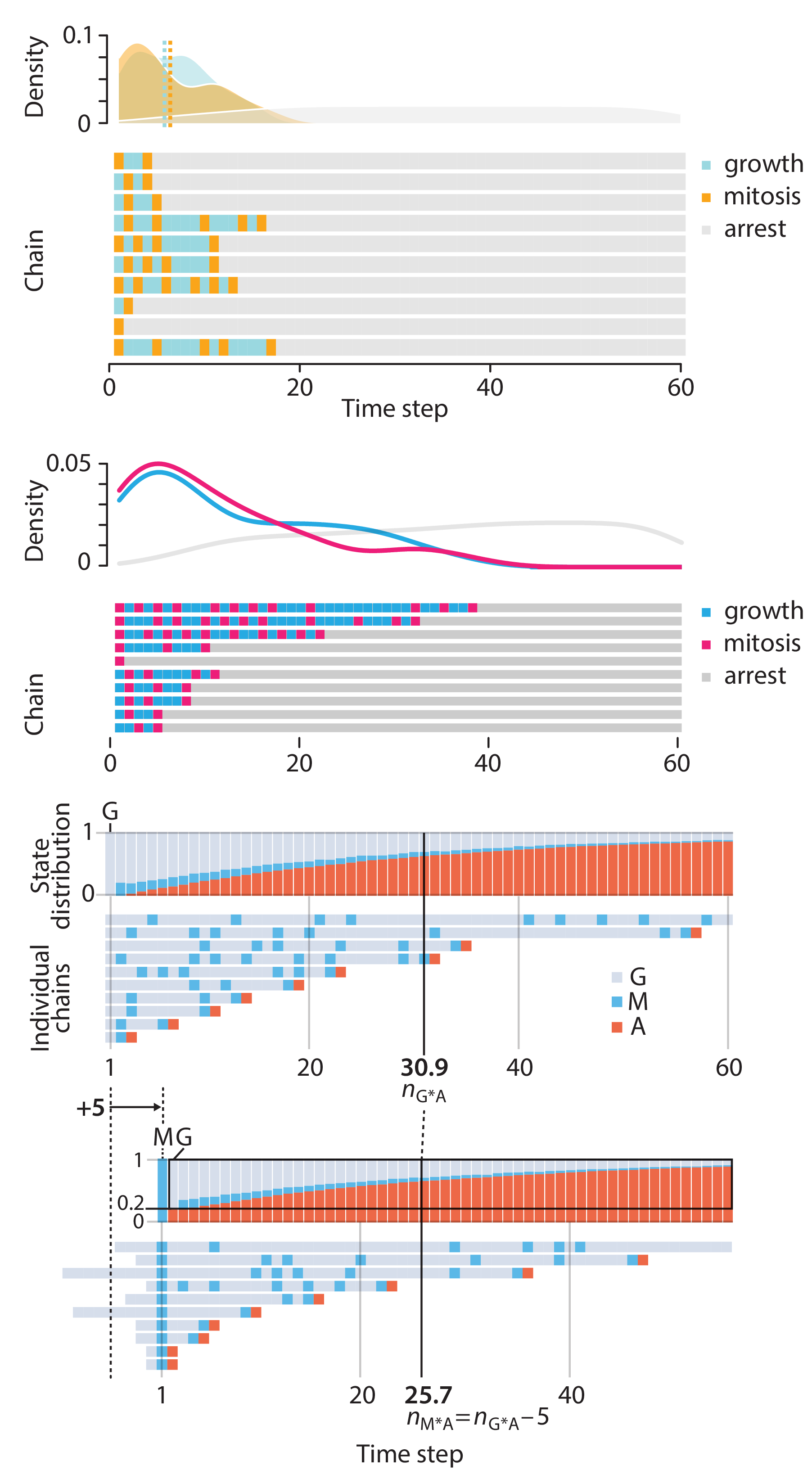

This month, we explore a related and powerful technique to address bias: propensity score weighting (PSW), which applies weights to each subject instead of matching (or discarding) them.

Kurz, C.F., Krzywinski, M. & Altman, N. (2025) Points of significance: Propensity score weighting. Nat. Methods 22:1–3.

Happy 2025 π Day—

TTCAGT: a sequence of digits

Celebrate π Day (March 14th) and sequence digits like its 1999. Let's call some peaks.

Crafting 10 Years of Statistics Explanations: Points of Significance

I don’t have good luck in the match points. —Rafael Nadal, Spanish tennis player

Points of Significance is an ongoing series of short articles about statistics in Nature Methods that started in 2013. Its aim is to provide clear explanations of essential concepts in statistics for a nonspecialist audience. The articles favor heuristic explanations and make extensive use of simulated examples and graphical explanations, while maintaining mathematical rigor.

Topics range from basic, but often misunderstood, such as uncertainty and P-values, to relatively advanced, but often neglected, such as the error-in-variables problem and the curse of dimensionality. More recent articles have focused on timely topics such as modeling of epidemics, machine learning, and neural networks.

In this article, we discuss the evolution of topics and details behind some of the story arcs, our approach to crafting statistical explanations and narratives, and our use of figures and numerical simulations as props for building understanding.

Altman, N. & Krzywinski, M. (2025) Crafting 10 Years of Statistics Explanations: Points of Significance. Annual Review of Statistics and Its Application 12:69–87.

Propensity score matching

I don’t have good luck in the match points. —Rafael Nadal, Spanish tennis player

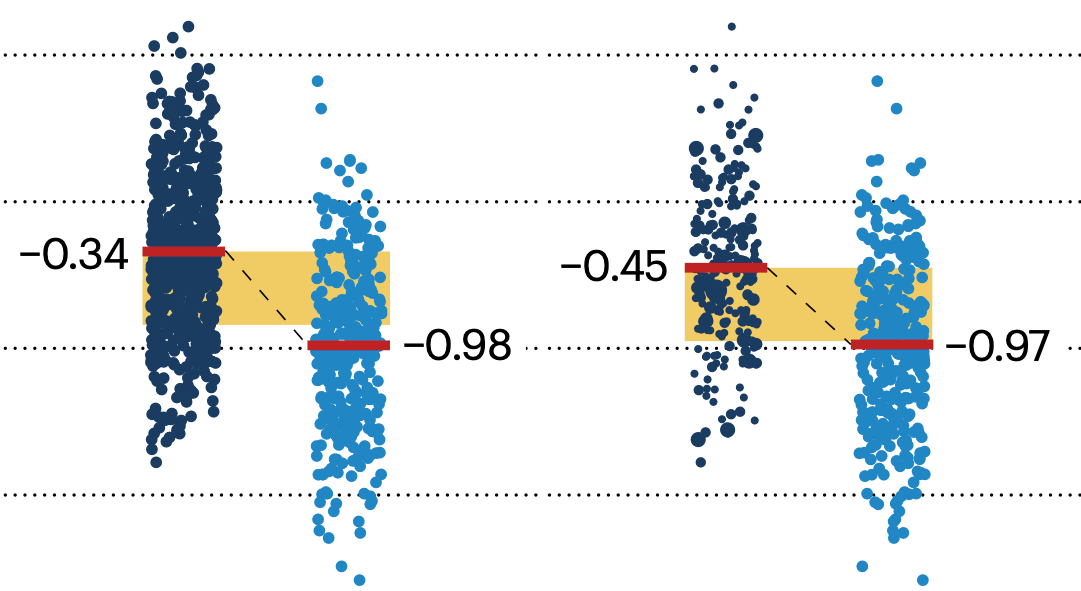

In many experimental designs, we need to keep in mind the possibility of confounding variables, which may give rise to bias in the estimate of the treatment effect.

If the control and experimental groups aren't matched (or, roughly, similar enough), this bias can arise.

Sometimes this can be dealt with by randomizing, which on average can balance this effect out. When randomization is not possible, propensity score matching is an excellent strategy to match control and experimental groups.

Kurz, C.F., Krzywinski, M. & Altman, N. (2024) Points of significance: Propensity score matching. Nat. Methods 21:1770–1772.

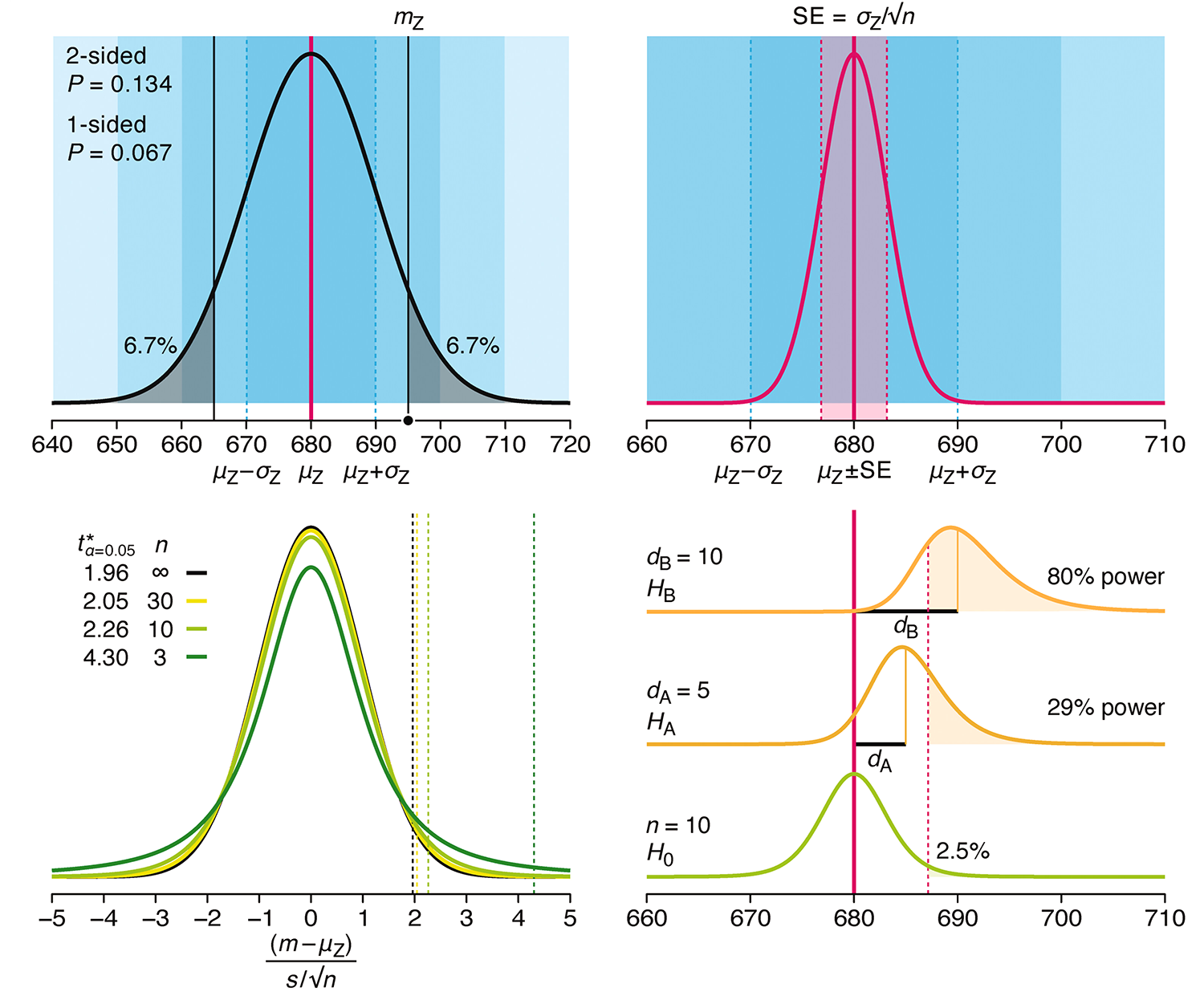

Understanding p-values and significance

P-values combined with estimates of effect size are used to assess the importance of experimental results. However, their interpretation can be invalidated by selection bias when testing multiple hypotheses, fitting multiple models or even informally selecting results that seem interesting after observing the data.

We offer an introduction to principled uses of p-values (targeted at the non-specialist) and identify questionable practices to be avoided.

Altman, N. & Krzywinski, M. (2024) Understanding p-values and significance. Laboratory Animals 58:443–446.