buy artwork

buy artwork

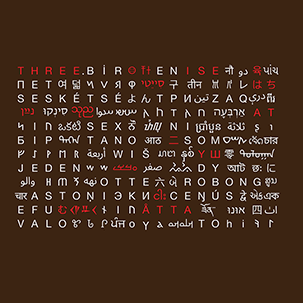

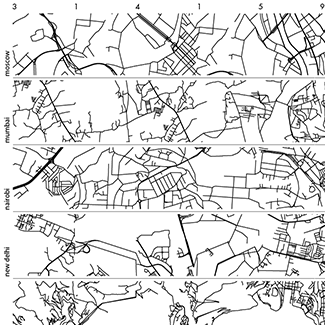

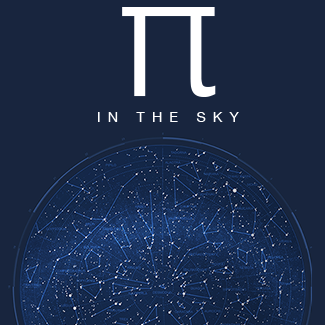

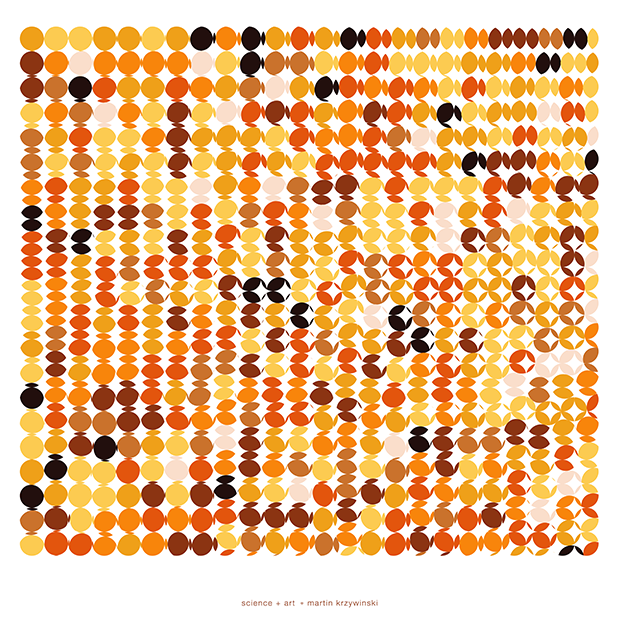

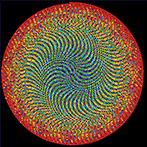

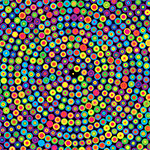

The art of Pi (`\pi`), Phi (`\phi`) and `e`

Numbers are a lot of fun. They can start conversations—the interesting number paradox is a party favourite: every number must be interesting because the first number that wasn't would be very interesting! Of course, in the wrong company they can just as easily end conversations.

The art here is my attempt at transforming famous numbers in mathematics into pretty visual forms, start some of these conversations and awaken emotions for mathematics—other than dislike and confusion

Numerology is bogus, but art based on numbers can be beautiful. Proclus got it right when he said (as quoted by M. Kline in Mathematical Thought from Ancient to Modern Times)

Wherever there is number, there is beauty.

—Proclus Diadochus

buy artwork

buy artwork

the numbers `\pi`, `\phi` and `e`

The consequence of the interesting number paradox is that all numbers are interesting. But some are more interesting than others—how Orwellian!

All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.

—George Orwell (Animal Farm)

Numbers such as `\pi` (or `\tau` if you're a revolutionary), `\phi`, `e`, `i = \sqrt{-1}`, and `0` have captivated imagination. Chances are at least one of them appears in the next physics equation you come across.

`\pi`

`\phi`

`e`

= 3.14159 26535 89793 23846 26433 83279 50288 41971 69399 ... = 1.61803 39887 49894 84820 45868 34365 63811 77203 09179 ... = 2.71828 18284 59045 23536 02874 71352 66249 77572 47093 ...

Of these three transcendental numbers, `\pi` (3.14159265...) is the most well known. It is the ratio of a circle's circumference to its diameter (`d = \pi r`) and appears in the formula for the area of the circle (`a = \pi r^2`).

buy artwork

buy artwork

The Golden Ratio (`\phi`, 1.61803398...) is the attractive proportion of values `a > b` that satisfy `{a+b}/2 = a/b`, which solves to `a/b = {1 + \sqrt{5}}/2`.

The last of the three numbers, `e` (2.71828182...) is Euler's number and also known as the base of the natural logarithm. It, too, can be defined geometrically—it is the unique real number, `e`, for which the function `f(x) = e^x` has a tangent of slope 1 at `x=0`. Like `\pi`, `e` appears throughout mathematics. For example, `e` is central in the expression for the normal distribution as well as the definition of entropy. And if you've ever heard of someone talking about log plots ... well, there's `e` again!

Two of these numbers can be seen together in mathematics' most beautiful equation, the Euler identity: `e^{i\pi} = -1`. The tau-oists would argue that this is even prettier: `e^{i\tau} = 1`.

accidentally similar

Did you notice how the 13th digit of all three numbers is the same (9)? This accidental similarity generates its own number—the Accidental Similarity Number (ASN).

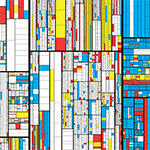

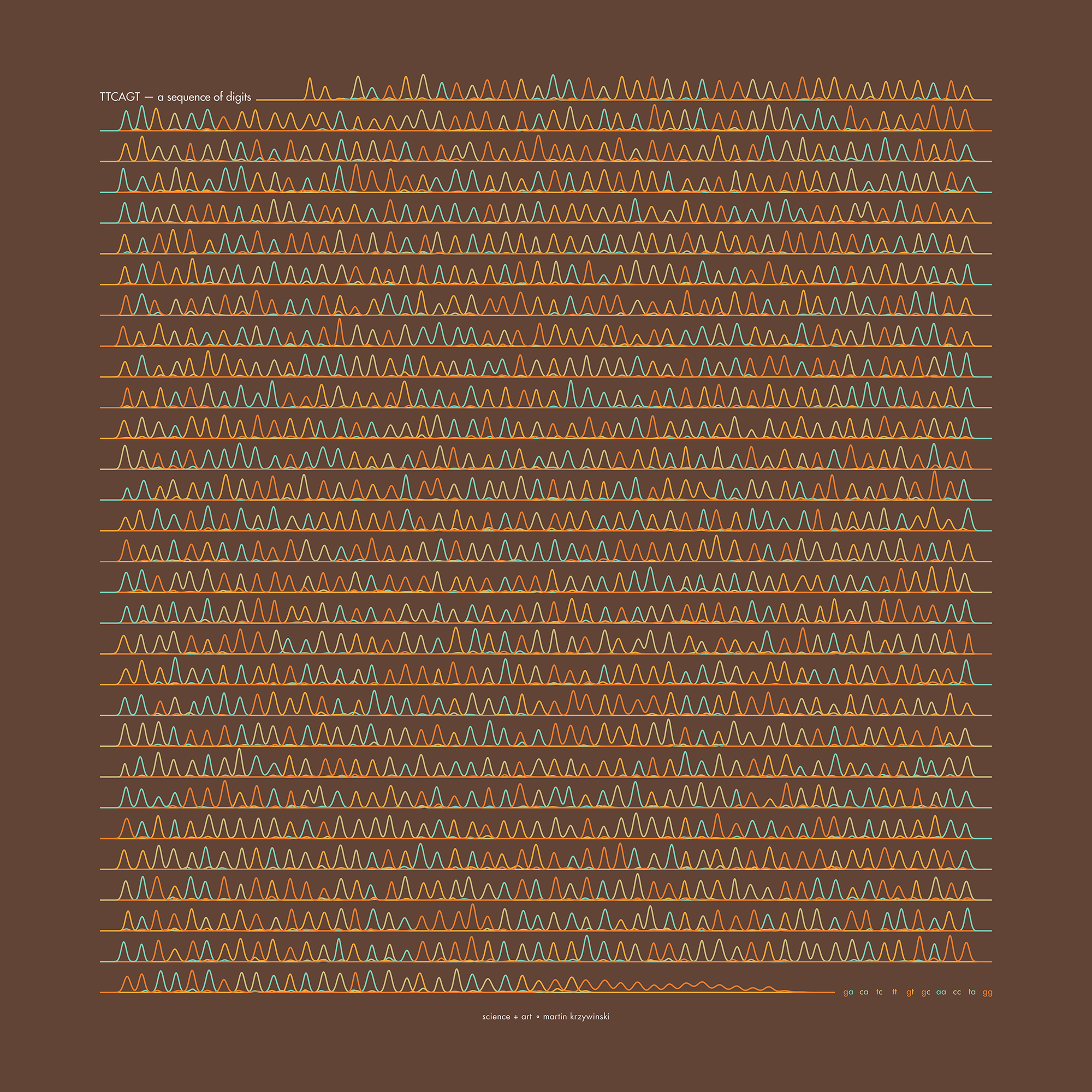

Beyond Belief Campaign BRCA Art

Fuelled by philanthropy, findings into the workings of BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes have led to groundbreaking research and lifesaving innovations to care for families facing cancer.

This set of 100 one-of-a-kind prints explore the structure of these genes. Each artwork is unique — if you put them all together, you get the full sequence of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 proteins.

Propensity score weighting

The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few. —Mr. Spock (Star Trek II)

This month, we explore a related and powerful technique to address bias: propensity score weighting (PSW), which applies weights to each subject instead of matching (or discarding) them.

Kurz, C.F., Krzywinski, M. & Altman, N. (2025) Points of significance: Propensity score weighting. Nat. Methods 22:1–3.

Happy 2025 π Day—

TTCAGT: a sequence of digits

Celebrate π Day (March 14th) and sequence digits like its 1999. Let's call some peaks.

Crafting 10 Years of Statistics Explanations: Points of Significance

I don’t have good luck in the match points. —Rafael Nadal, Spanish tennis player

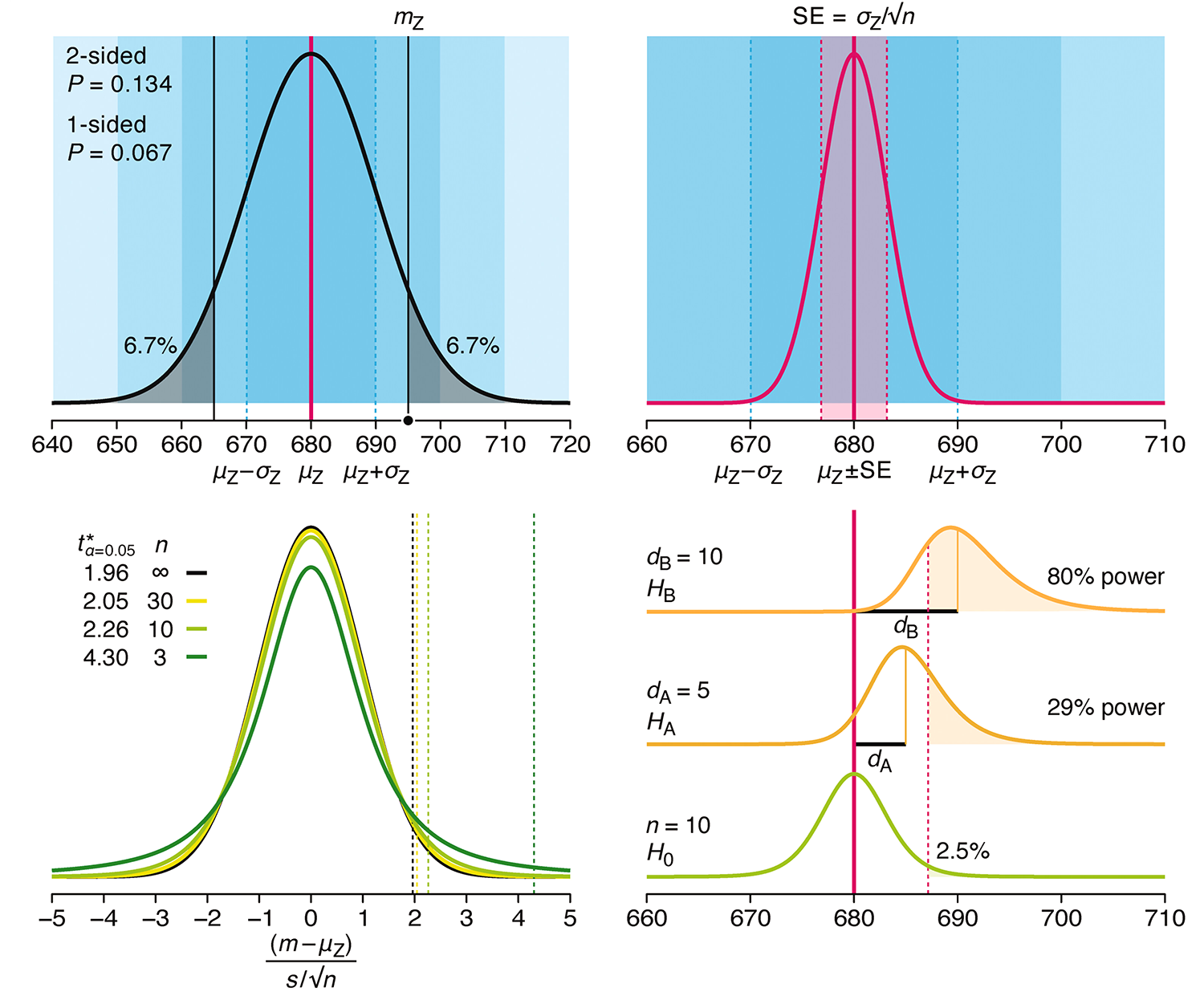

Points of Significance is an ongoing series of short articles about statistics in Nature Methods that started in 2013. Its aim is to provide clear explanations of essential concepts in statistics for a nonspecialist audience. The articles favor heuristic explanations and make extensive use of simulated examples and graphical explanations, while maintaining mathematical rigor.

Topics range from basic, but often misunderstood, such as uncertainty and P-values, to relatively advanced, but often neglected, such as the error-in-variables problem and the curse of dimensionality. More recent articles have focused on timely topics such as modeling of epidemics, machine learning, and neural networks.

In this article, we discuss the evolution of topics and details behind some of the story arcs, our approach to crafting statistical explanations and narratives, and our use of figures and numerical simulations as props for building understanding.

Altman, N. & Krzywinski, M. (2025) Crafting 10 Years of Statistics Explanations: Points of Significance. Annual Review of Statistics and Its Application 12:69–87.

Propensity score matching

I don’t have good luck in the match points. —Rafael Nadal, Spanish tennis player

In many experimental designs, we need to keep in mind the possibility of confounding variables, which may give rise to bias in the estimate of the treatment effect.

If the control and experimental groups aren't matched (or, roughly, similar enough), this bias can arise.

Sometimes this can be dealt with by randomizing, which on average can balance this effect out. When randomization is not possible, propensity score matching is an excellent strategy to match control and experimental groups.

Kurz, C.F., Krzywinski, M. & Altman, N. (2024) Points of significance: Propensity score matching. Nat. Methods 21:1770–1772.

Understanding p-values and significance

P-values combined with estimates of effect size are used to assess the importance of experimental results. However, their interpretation can be invalidated by selection bias when testing multiple hypotheses, fitting multiple models or even informally selecting results that seem interesting after observing the data.

We offer an introduction to principled uses of p-values (targeted at the non-specialist) and identify questionable practices to be avoided.

Altman, N. & Krzywinski, M. (2024) Understanding p-values and significance. Laboratory Animals 58:443–446.