Eggnauts — Engineers Launch Model Rockets at UBC

contents

The contest took place at UBC in 2005. The goal was to launch a rocket at least 150m into the air with a payload of an egg and bottle of maple syrup. And — you guess it — the egg had to be returned back to earth in relative safety.

I was first in line to see the egg carnage, which promised to be the best part of the show.

I mean, who wants to see whole eggs landing in relative safety anyway?

I was well positioned with my camera for the launch. After a few times being told to step even further back — so that I would not get egg on my face, I'm sure — I settled into a position that was both safe and a good lookout.

Unfortunately, from my vantage point I was shooting right into the sun, so the photos are a little bleached out. I also had the 24-70mm f/2.8L on my 20D so I couldn't get good reach. The photos here are 100% crops.

Shooting at 5 fps, I caught the first sign of the plume developing around the rocket as its engines ignited.

After the second frame, the acceleration was rapid and the rocket lifted off to 2-3 m before my next frame.

And it was on its way!

And then it just kept going, and going and going. It finally disappeared travelling west. Nobody heard from the egg again.

After the first launch I repositioned myself to face south, with the sun at my back. After the excitement of the egg launched into orbit, I could hardly anticipate what came next. I was in for a show so exciting that all remaining launches were promptly canceled. Read on.

Before the launch, I caught the engineers looking over their rocket. Handling it lovingly, they were making sure that the eggnaut and maple syrup were snuggly nestled into the payload canister.

The tension was palpable. Would it launch? Would it reach 150m? Would the eggnaut return to tell the tale without cracking?

Once again, the shutter flapped at 5 fps as the rocket took off. This time, I caught the start of the plume at just the right time and captured the rocket take off in the first few frames.

The trip started solidly for our eggnaut. The launch was timely, and more importantly, the rocket was travelling vertically - upwards. Would the egg make a career out of it? Just as our hopes were rising, we realized that something was terribly wrong. Shortly after take off, it became clear that the eggnaut was doomed. We didn't want to believe it at first, but it was obvious that the flight plan was taking a turn for the worse.

The rocket began to spin wildly. To add, it began to turn to traveling the directly of the shocked onlookers and the parking lot. It was not longer just about the egg anymore. Fear gripped me, but I kept shooting. The next four frames reveal the horrible events that sealed the eggnaut's doom. In the second of the frames, an unplanned explosion is clearly seen. The rocket is undeterred by this, and continues to fly in the direction of the spectators.

The travel path became more erratic, and only a few seconds later the last booster cut-off. The eggnaut, perhaps still viable, was in free fall. Falling, accelerating - right into the parking lot.

I started running towards the extrapolated crash site, as I heard a thud. When I got there, a small crowd already formed around the impact site. Someone called for an eggdoctor. In my first shot of the macabre, only the parachute, never deployed, is seen. The true extent of the disaster is covered by the figure of solemn child.

Rapidly, the team of engineers arrived on site. Although the rocket spent about 10 fateful seconds in the air, it only traveled about 30 meters, as the crow flies (which it does much longer).

Of course, all eyes were on the contents. Was the eggnaut safe? Perhaps by some earthly miracle, the impact was not severe enough. Of course, even before the rocket payload canister was opened, we all knew that the sickly thud that placed the rocket less than a meter from a car was a mortal hit to our airborne friend.

The next photo captures the human moment of tragedy. The team lead finally realizes that nothing survived. The man behind him and to the right bites his lip in disappointment and shock.

The next photo reveals the payload - now turned into an ogrish paste of eggnaut and maple syrup.

The third team stood by - their launch canceled. Their hearts were heavy with the tragedy of the previous team's horrible flame-out. One of the team members is seen here so distraught that he kneals and leans on his rocket for support.

Yet they could not help but imagine - how far would their eggnaut have traveled?

Beyond Belief Campaign BRCA Art

Fuelled by philanthropy, findings into the workings of BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes have led to groundbreaking research and lifesaving innovations to care for families facing cancer.

This set of 100 one-of-a-kind prints explore the structure of these genes. Each artwork is unique — if you put them all together, you get the full sequence of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 proteins.

Propensity score weighting

The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few. —Mr. Spock (Star Trek II)

This month, we explore a related and powerful technique to address bias: propensity score weighting (PSW), which applies weights to each subject instead of matching (or discarding) them.

Kurz, C.F., Krzywinski, M. & Altman, N. (2025) Points of significance: Propensity score weighting. Nat. Methods 22:1–3.

Happy 2025 π Day—

TTCAGT: a sequence of digits

Celebrate π Day (March 14th) and sequence digits like its 1999. Let's call some peaks.

Crafting 10 Years of Statistics Explanations: Points of Significance

I don’t have good luck in the match points. —Rafael Nadal, Spanish tennis player

Points of Significance is an ongoing series of short articles about statistics in Nature Methods that started in 2013. Its aim is to provide clear explanations of essential concepts in statistics for a nonspecialist audience. The articles favor heuristic explanations and make extensive use of simulated examples and graphical explanations, while maintaining mathematical rigor.

Topics range from basic, but often misunderstood, such as uncertainty and P-values, to relatively advanced, but often neglected, such as the error-in-variables problem and the curse of dimensionality. More recent articles have focused on timely topics such as modeling of epidemics, machine learning, and neural networks.

In this article, we discuss the evolution of topics and details behind some of the story arcs, our approach to crafting statistical explanations and narratives, and our use of figures and numerical simulations as props for building understanding.

Altman, N. & Krzywinski, M. (2025) Crafting 10 Years of Statistics Explanations: Points of Significance. Annual Review of Statistics and Its Application 12:69–87.

Propensity score matching

I don’t have good luck in the match points. —Rafael Nadal, Spanish tennis player

In many experimental designs, we need to keep in mind the possibility of confounding variables, which may give rise to bias in the estimate of the treatment effect.

If the control and experimental groups aren't matched (or, roughly, similar enough), this bias can arise.

Sometimes this can be dealt with by randomizing, which on average can balance this effect out. When randomization is not possible, propensity score matching is an excellent strategy to match control and experimental groups.

Kurz, C.F., Krzywinski, M. & Altman, N. (2024) Points of significance: Propensity score matching. Nat. Methods 21:1770–1772.

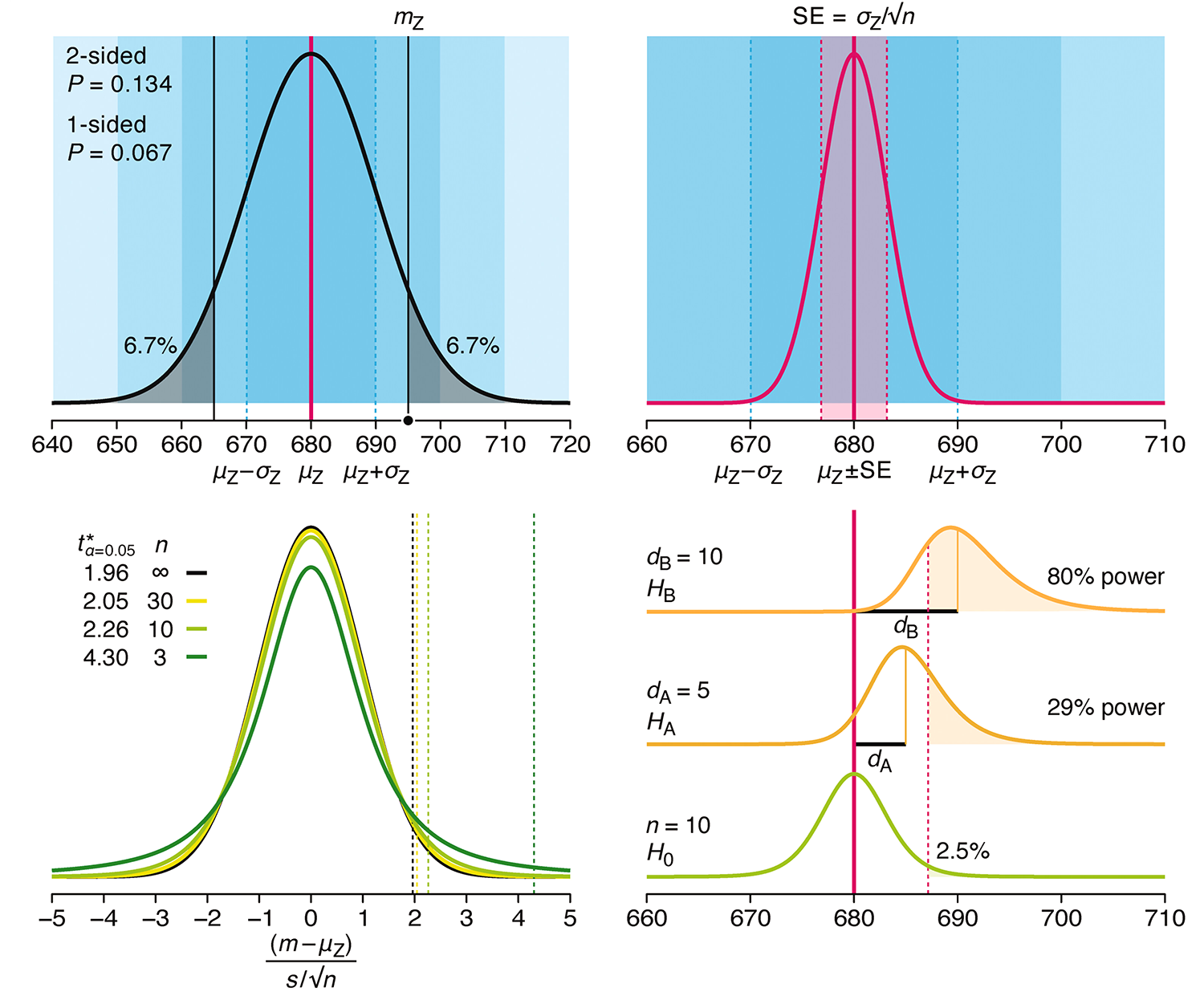

Understanding p-values and significance

P-values combined with estimates of effect size are used to assess the importance of experimental results. However, their interpretation can be invalidated by selection bias when testing multiple hypotheses, fitting multiple models or even informally selecting results that seem interesting after observing the data.

We offer an introduction to principled uses of p-values (targeted at the non-specialist) and identify questionable practices to be avoided.

Altman, N. & Krzywinski, M. (2024) Understanding p-values and significance. Laboratory Animals 58:443–446.