#hitchens

Christopher Hitchens—Out of Letters

contents

The images shown here were created as part of my ASCII Art project, which extends ASCII art to include

- proportionally spaced fonts

- a variety of font weights in a single image

- both tone and structure of the image to select characters

- fixed strings to render an image in legible text

Applying the code to images of Hitchens was motivated by my own deep love of Hitchens and a typographic portrait of Christopher Hitchens, created out of Gill Sans letters by Miles Chic at Capilano University.

Also, what's the reason for reason this season? Why, Hitchmas, of course.

All images are generated using Gotham, with up to 8 weights (Extra Light to Ultra). Each image includes size and characters used for the image. I give the absolute type size, though only useful to know in relative terms to the size of the image and other images drawn with the same method. The color of text in each layer is the same—black— but font weight may vary.

Some images are generated using more than one layer of ASCII. In some cases the characters used in each layer are different.

As the font size is reduced, greater detail and contrast can be achieved.

By setting the image with a fixed string, such as a short quote or longer body of text, detail is lost but the ASCII representation takes on more meaning.

Images take on detail when several rotated layers of text is used. Each of the images below is composed of more than one layer, starting with a 2-layer image which uses the uppercase alphabet at 0 and 90 degrees.

Meaning can be added to the image by using different text in each layer. In the examples below, I set the same image using the pair "Godisnotgreat" (at 0 degrees) and "religionpoisonseverything" (at 90 degrees). In the second example, I use the unlikely combination of "Jesus" and "Mohammad"—inspired by Jesus and Mo.

When rotated layers contain punctuation, very high level of detail can be achieved.

The image below is made out of layers that contain only forward (/) and back (\) slashes.

The image below is made using only the period character in three layers rotated at –45, 0 and 45 degrees. Although the image looks like a pixelated version of the original—it is more than that. It is a typeset representation that uses 8 weights of Gotham. Character spacing between periods is informed by font metrics.

The three images below show the difference between using a variety of punctuation characters and setting an image using a block of text. The first image uses "8 X x" and common punctuation.

I use Hitchslap 9 for the first image below, and all the Hitchslaps for the second image. When setting an image in using a block of text, the choice of character at any position is fixed and only the font weight is allowed to vary. When the text is relatively short (e.g. Hitchslap 9 is 544 characters and is repeated 50 times in the image), rivers of space appear in the image.

In both cases, the image is very recognizable.

When an image of text is set with the text itself, you have recursive ASCII art. Below is Hitchslap 2, set with itself. In the image, the font is Gotham and the text used to asciify the image is also Gotham.

It makes ordinary moral people, compels them, forces them, in some cases orders them do disgusting wicked unforgivable things. There's no expiation for the generations of misery and suffering that religion has inflicted in this way and continues to inflict. And I still haven't heard enough apology for it. — Christopher Hitchens

The quote is 307 characters long and is repeated 391 times in the image.

In principle, the process of asciifying text with text can be repeated, by using the asciified image as input for asciification with progressively smaller text.

Propensity score weighting

The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few. —Mr. Spock (Star Trek II)

This month, we explore a related and powerful technique to address bias: propensity score weighting (PSW), which applies weights to each subject instead of matching (or discarding) them.

Kurz, C.F., Krzywinski, M. & Altman, N. (2025) Points of significance: Propensity score weighting. Nat. Methods 22:1–3.

Happy 2025 π Day—

TTCAGT: a sequence of digits

Celebrate π Day (March 14th) and sequence digits like its 1999. Let's call some peaks.

Crafting 10 Years of Statistics Explanations: Points of Significance

I don’t have good luck in the match points. —Rafael Nadal, Spanish tennis player

Points of Significance is an ongoing series of short articles about statistics in Nature Methods that started in 2013. Its aim is to provide clear explanations of essential concepts in statistics for a nonspecialist audience. The articles favor heuristic explanations and make extensive use of simulated examples and graphical explanations, while maintaining mathematical rigor.

Topics range from basic, but often misunderstood, such as uncertainty and P-values, to relatively advanced, but often neglected, such as the error-in-variables problem and the curse of dimensionality. More recent articles have focused on timely topics such as modeling of epidemics, machine learning, and neural networks.

In this article, we discuss the evolution of topics and details behind some of the story arcs, our approach to crafting statistical explanations and narratives, and our use of figures and numerical simulations as props for building understanding.

Altman, N. & Krzywinski, M. (2025) Crafting 10 Years of Statistics Explanations: Points of Significance. Annual Review of Statistics and Its Application 12:69–87.

Propensity score matching

I don’t have good luck in the match points. —Rafael Nadal, Spanish tennis player

In many experimental designs, we need to keep in mind the possibility of confounding variables, which may give rise to bias in the estimate of the treatment effect.

If the control and experimental groups aren't matched (or, roughly, similar enough), this bias can arise.

Sometimes this can be dealt with by randomizing, which on average can balance this effect out. When randomization is not possible, propensity score matching is an excellent strategy to match control and experimental groups.

Kurz, C.F., Krzywinski, M. & Altman, N. (2024) Points of significance: Propensity score matching. Nat. Methods 21:1770–1772.

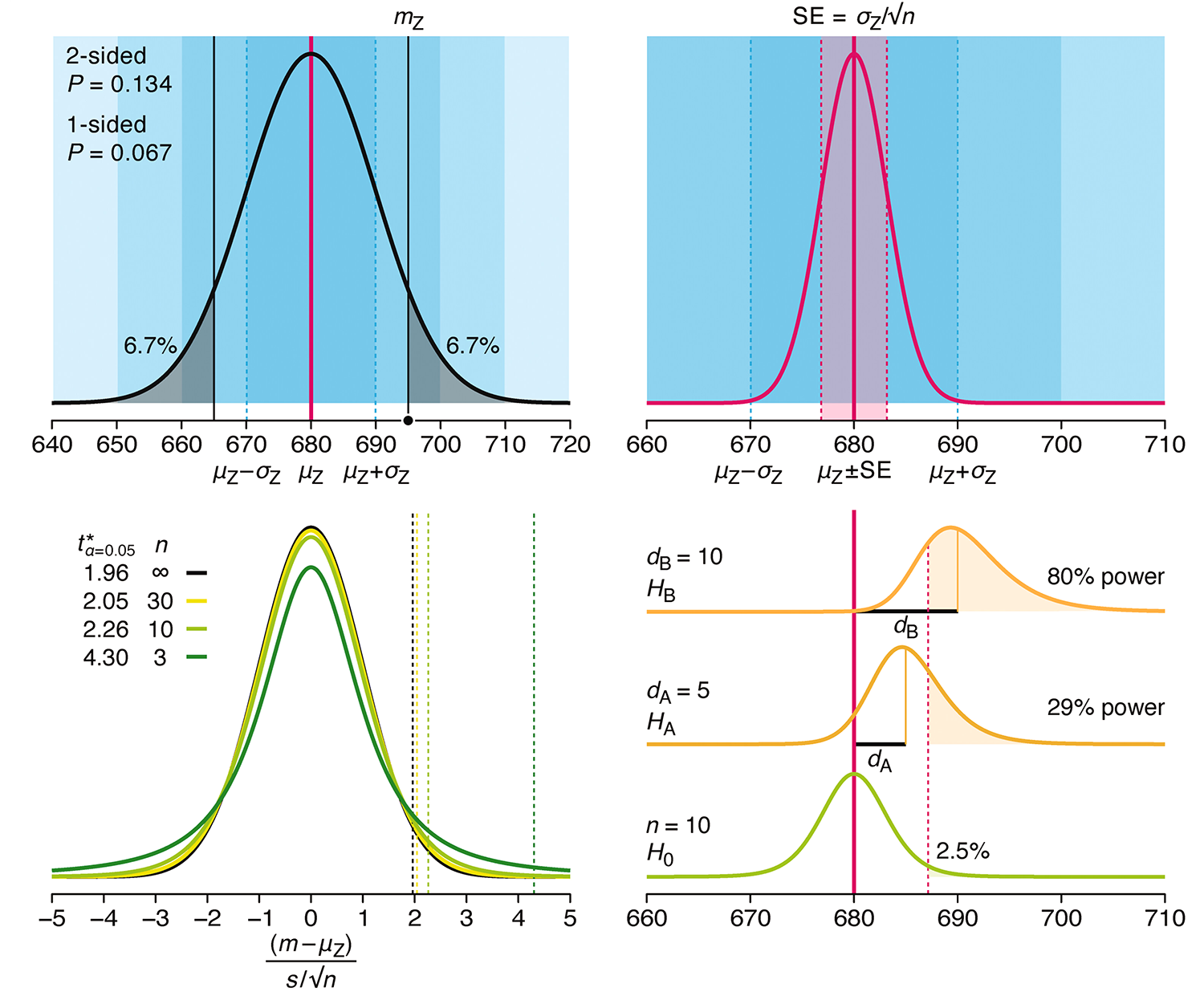

Understanding p-values and significance

P-values combined with estimates of effect size are used to assess the importance of experimental results. However, their interpretation can be invalidated by selection bias when testing multiple hypotheses, fitting multiple models or even informally selecting results that seem interesting after observing the data.

We offer an introduction to principled uses of p-values (targeted at the non-specialist) and identify questionable practices to be avoided.

Altman, N. & Krzywinski, M. (2024) Understanding p-values and significance. Laboratory Animals 58:443–446.

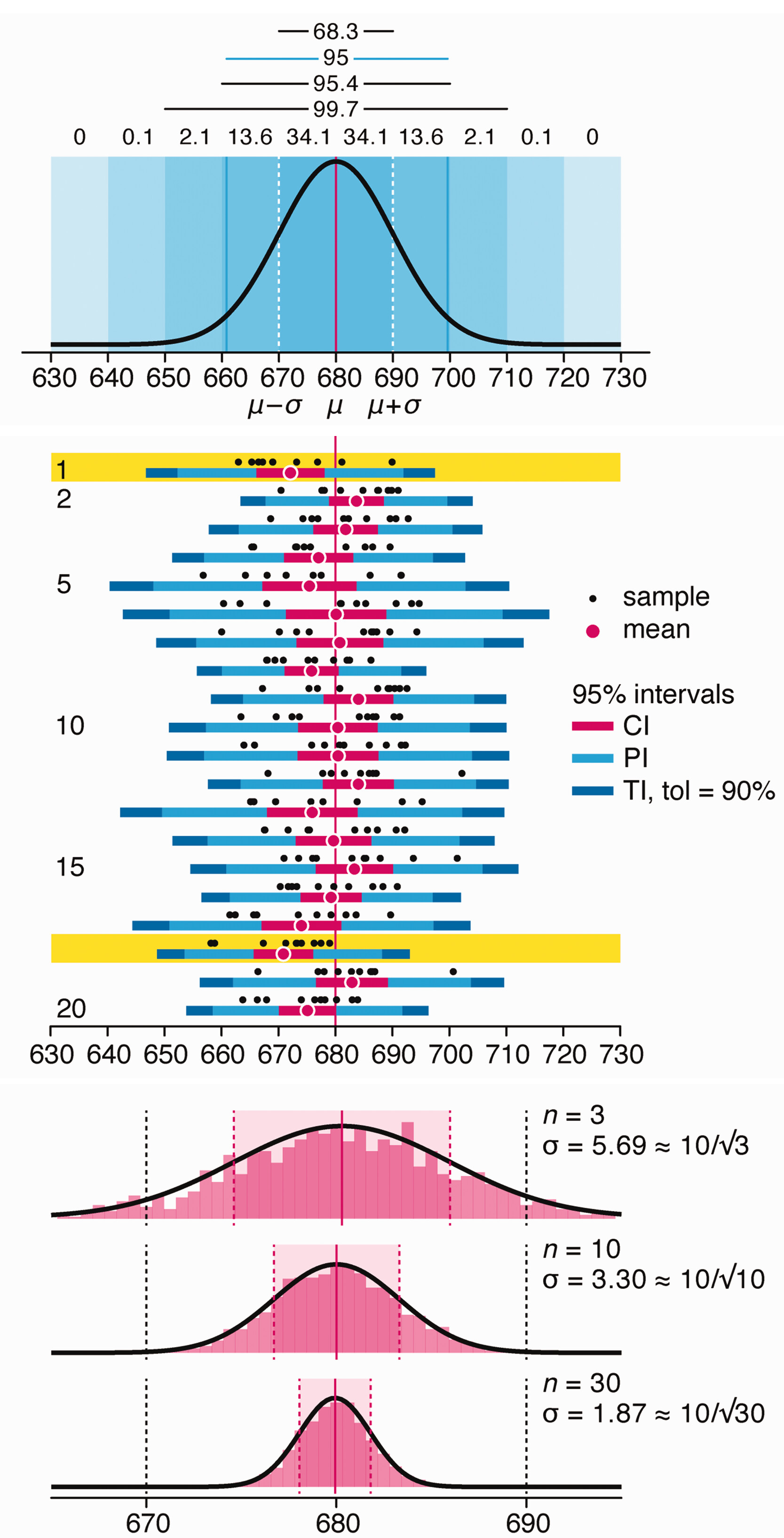

Depicting variability and uncertainty using intervals and error bars

Variability is inherent in most biological systems due to differences among members of the population. Two types of variation are commonly observed in studies: differences among samples and the “error” in estimating a population parameter (e.g. mean) from a sample. While these concepts are fundamentally very different, the associated variation is often expressed using similar notation—an interval that represents a range of values with a lower and upper bound.

In this article we discuss how common intervals are used (and misused).

Altman, N. & Krzywinski, M. (2024) Depicting variability and uncertainty using intervals and error bars. Laboratory Animals 58:453–456.