buy artwork

buy artwork

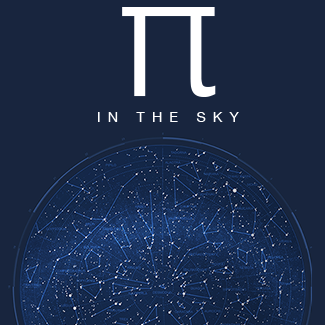

`\pi` Day 2017 Art Posters - Star charts and extinct animals and plants

On March 14th celebrate `\pi` Day. Hug `\pi`—find a way to do it.

For those who favour `\tau=2\pi` will have to postpone celebrations until July 26th. That's what you get for thinking that `\pi` is wrong. I sympathize with this position and have `\tau` day art too!

If you're not into details, you may opt to party on July 22nd, which is `\pi` approximation day (`\pi` ≈ 22/7). It's 20% more accurate that the official `\pi` day!

Finally, if you believe that `\pi = 3`, you should read why `\pi` is not equal to 3.

Caelum non animum mutant qui trans mare currunt.

—Horace

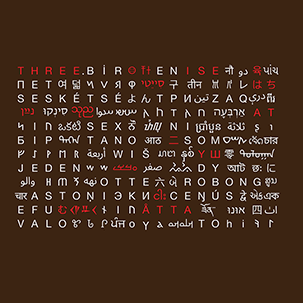

This year: creatures that don't exist, but once did, in the skies.

This year's `\pi` day song is Exploration by Karminsky Experience Inc. Why? Because "you never know what you'll find on an exploration".

create myths and contribute!

Want to contribute to the mythology behind the constellations in the `\pi` in the sky? Many already have a story, but others still need one. Please submit your stories!

This year's `\pi` day art goes to space and there finds creatures that once called Earth home.

Well, I don't know if they called it home—at least a few thought it was a terribly inhospitable. All thought it was unforgivingly Darwinian.

buy artwork

buy artwork

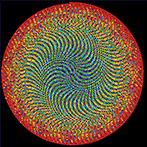

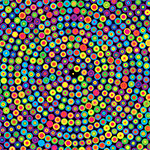

the digits of `\pi` as a star catalogue

I asked the question: what happens if you interpret the digits of `\pi` as a catalogue of stars? What would the patterns in the sky look like? And, would they have stories? A couple of weeks later—and a few adventures down the rabbit holes of topographical projections—I found the answer.

The digits of Pi are interpreted as a star catalogue. Starting from the beginning of `\pi`, each block of 12 digits is taken to be the `(x, y, z)` coordinates of a star and its absolute magnitude, which defines its brightness at a fixed distance. After sampling 12 million digits, which yields 1,000,000 stars, the stars are projected onto the celestial sphere to generate longitude and latitude coordinates from the perspective of an observer who is placed at center of the stars. The distance to the star is used to calculate the apparent magnitude—how bright it will appear on the sky chart.

buy artwork

buy artwork

buy artwork

buy artwork

Of course, a star chart would not be complete without constellations. While the digits of `\pi` are taken to be a universal catalog of stars, it is up to the observer to subjectively interpret the patterns and find stories in the sky. Among the 40,000 stars drawn in the chart, 80 extinct species are honored as constellations—creatures range across time periods and geographical location and play together in the sky. And much like the constellations that you might have seen in the real sky (the hunter Orion and winged-horse Pegasus) the `\pi` in the sky patterns represent creatures that do not exist.

The twist? They all once did!

chart variations

Charts are available in blue, black and white and sepia.

buy artwork

buy artwork

buy artwork

buy artwork

stories in the sky

There are indeed stories in the sky and many of them haven't yet been told. Below are just some of them.

More stories are available in the details about each constellation. There, for each animal you can find the common name, Latin name, when it was extinct and a link to Wikipedia to learn more about the animal. Many have stories which they would love to share with you.

raphus — egg guardian extraordinaire

The Dodo bird (Raphus cucullatus) is vigilantly guarding his eggs—the clusters of stars just north of &alpha Raphus (the first brightest star in the constellation) and south of β Raphus (the second brightest star). He hardly seems to care about the pestering River Mayfly (Acanthometropus pecatonica), who is trying to draw his attention.

desmodus — nightly escape attempt

Desmodus, the giant vampire bat (Desmodus draculae) is said to be trying to escape the dome of the sky each night. You might see his shape fluttering up into the top of the northern hemisphere.

basilosaurus — chasing the light in the deep

The king lizard Basilosaurus (Basilosaurus cetoides) dives deeper and deeper at the bottom of the south hemisphere, as he chases the light of the bright magnitude 1.8 star α Basilosaurus, which sits at the very bottom of the chart.

quagga and aurochs — figuring out the stripes

There is plenty of land mass in teh north, where huge creatures like the mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius), sturdy aurochs (Bos primigenius) and the comical Quagga (Equus quagga quagga) run again. The Quagga cannot figure out his stripes and is seen frequently talking to the Aurochs, seeking his advice about the predicament of his patterns.

megalodon, rodhocetus and tecopa — the terror and the terrorized

At the tip of the southern hemisphere drama unfolds as the monster shark Megalodon (Carcharodon megalodon) gives chase to the Tecopa pupfish (Cyprinodon nevadensis calidae) and Rodhocetus (Rodhocetus kasrani). Rodhocetus was an early whale that possessed land mammal characteristics and the story goes that he escaped Megalodon and lived out his life on the land, never returning to the sea.

camptor, mariana, alaotra and tadorna — I'm not a duck!

The south hemisphere also has plenty of calmer waters, where all manners of floating birds come for a swim and chat. These are represented by the triangular constellations of Camptor (Camptorhynchus labradorius, the Labrador duck), Alaotra grebe (Tachybaptus rufolavatus), Mariana mallard (Anas oustaleti) and the Korean crested shelduck (Tadorna cristata). Rumor has it Tadorna may have snuck into the sky without permission—while not seen since the 1960’s, some say the duck isn't actually extinct! Alaotra is frustrated that Tadorna seems to get all the attention. Often confused for a duck, Alaotra would love you to know that she's in fact a grebe. She's very proud of this fact, despite of being prone to falls due to some biomechanical issues having to do with foot placement.

yersinia — don't come close

Don't let Yersinia's small size fool you. The Black Death (Yersinia pestis) may be the smallest creature in the sky, but she'll liquify your insides before you can memorize the 80 constellations. Perhaps out of all the creatures in the sky, this is the one we're happy to see go. But, because it's small, you can never be quite sure Yersinia isn't extinct but merely hiding. Or waiting.

pipilo — flocking across

Pipilo is a rare flocking constellation and breaks the rule that a constellation should be a single connected component. Its stars are connected a loose pattern of pairs and show a flock of Bermuda towhees (Pipilo naufragus) crossing from the north to south hemispheres.

o'ahu 'akepa — two is such a lonely number

Like Pipilo, the O'ahu 'akepa (Loxops wolstenholmei) is the only other multi-part constellation. Here, a pair of akepas are chatting and spreading rumors that Tadorna isn't actually extinct.

bron and compsognathus — big brothers and little friends

It's hard to be bigger than Bron (Brontosaurus excelsus), who must pay great attention not to step on his frolicking friend Compsognathus (Compsognathus longipes), who seeks to find protection in Bron's shadow. Some believe that if Bron stretches his neck, he can look above the sky!

pinta and cylindraspis — a friend for the end of the earth

Ever since Cylindraspis (Cylindraspis indica) heard that Pinta (Chelonoidis abingdonii) was the last of his kind, he decided to keep him company. They can be seen going for a very slow walk at the bottom of the sky, kept their by their heavy shells. The last Pinta—a turtle named Lonesome George—died in 2012.

xerces and Palaeoaldrovanda — flying flowers and hungry flowers

Xerces (Glaucopsyche xerces) is the only thing that is more brilliant than the blue sky itself. Some say that butterflies are flying flowers and Xerces is never seen far from Palaeoaldrovanda. He must be careful though. Rumor has it Palaeoaldrovanda was related to the carnivorous plant genus Aldrovanda! Nobody wants to take that chance.

araucaria — shelter for flying customers

Xerces (Glaucopsyche xerces) is the only thing that is more brilliant than the blue sky itself. Some say that butterflies are flying flowers and Xerces is never seen far from Palaeoaldrovanda. He must be careful though. Rumor has it Palaeoaldrovanda was related to the carnivorous plant genus Aldrovanda! Nobody wants to take that chance.

araucaria — too large for the sky

Araucaria (Araucaria mirabilis) is truly a marvel and it is too big to fit in the sky! The constellation only shows the canopy and does not include the tree trunk—which was known to reach a height of 100 m. Araucaria offers plenty of protection and has many flying friends all around, including Urania, Moho and WhĒkau. Just a little further are the ducks (and a grebe), Camptor, Mariana, Tadorna and Alaotra. They would love to visit Araucaria but worry that they are too heavy to perch on her branches.

ardea and aepyronis — who can see beyond the sky first?

The story goes that Camelops (Camelops kansansus) played a joke on Ardea (Ardea bennuides) and Aepyronis (Aepyornis maximus). He said "You both have long necks. But who has the longest? The first who can stretch far enough and tell me what is beyond the sky wins." To this day, Both Ardea and Aepyronis are seen straining their necks trying to win the bet.

Beyond Belief Campaign BRCA Art

Fuelled by philanthropy, findings into the workings of BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes have led to groundbreaking research and lifesaving innovations to care for families facing cancer.

This set of 100 one-of-a-kind prints explore the structure of these genes. Each artwork is unique — if you put them all together, you get the full sequence of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 proteins.

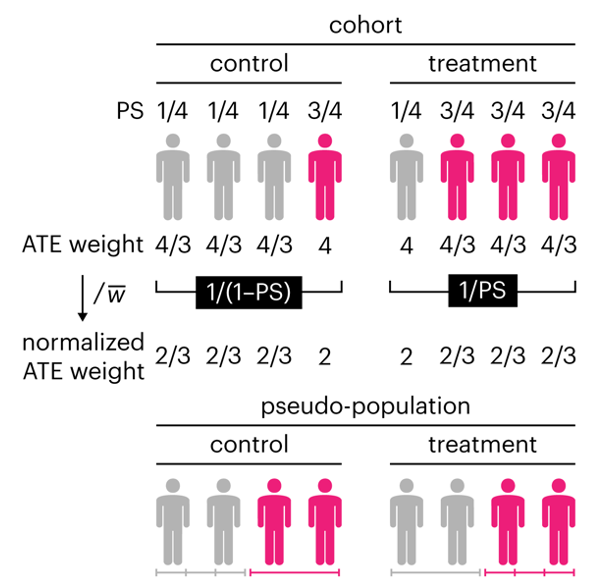

Propensity score weighting

The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few. —Mr. Spock (Star Trek II)

This month, we explore a related and powerful technique to address bias: propensity score weighting (PSW), which applies weights to each subject instead of matching (or discarding) them.

Kurz, C.F., Krzywinski, M. & Altman, N. (2025) Points of significance: Propensity score weighting. Nat. Methods 22:1–3.

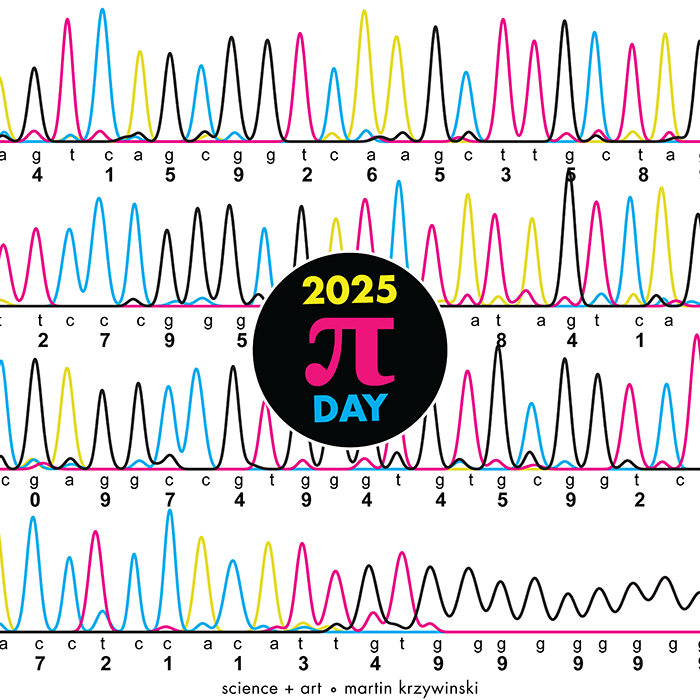

Happy 2025 π Day—

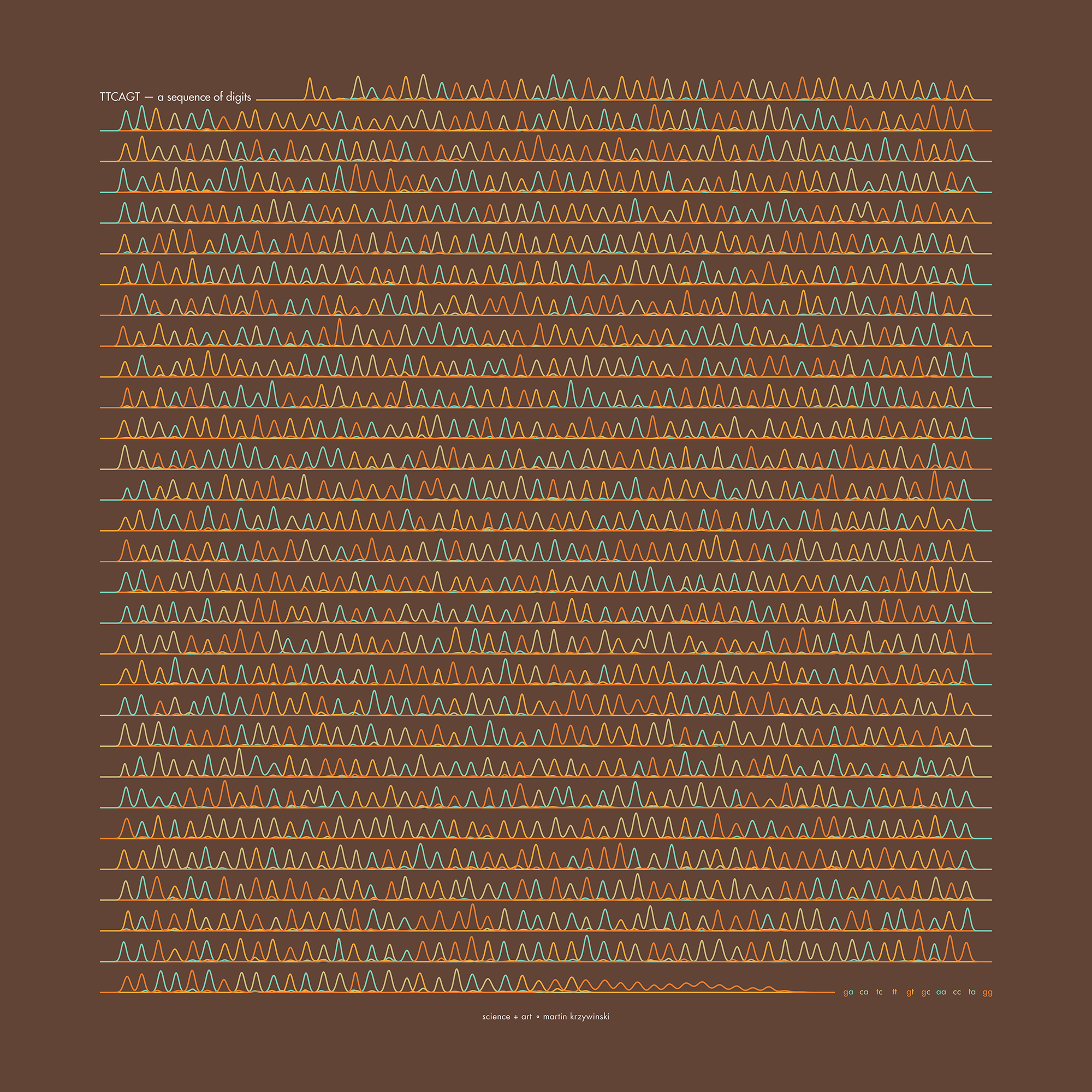

TTCAGT: a sequence of digits

Celebrate π Day (March 14th) and sequence digits like its 1999. Let's call some peaks.

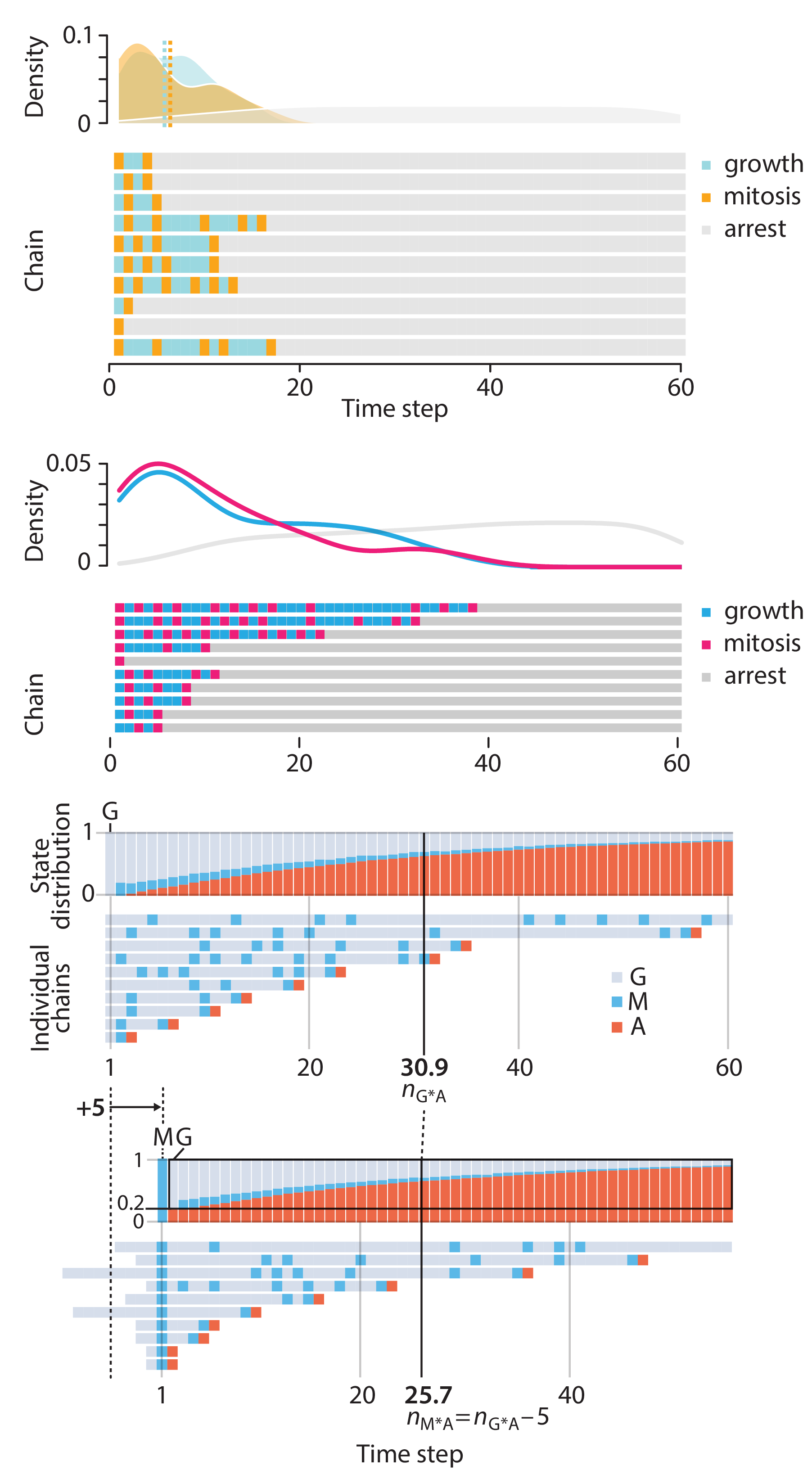

Crafting 10 Years of Statistics Explanations: Points of Significance

I don’t have good luck in the match points. —Rafael Nadal, Spanish tennis player

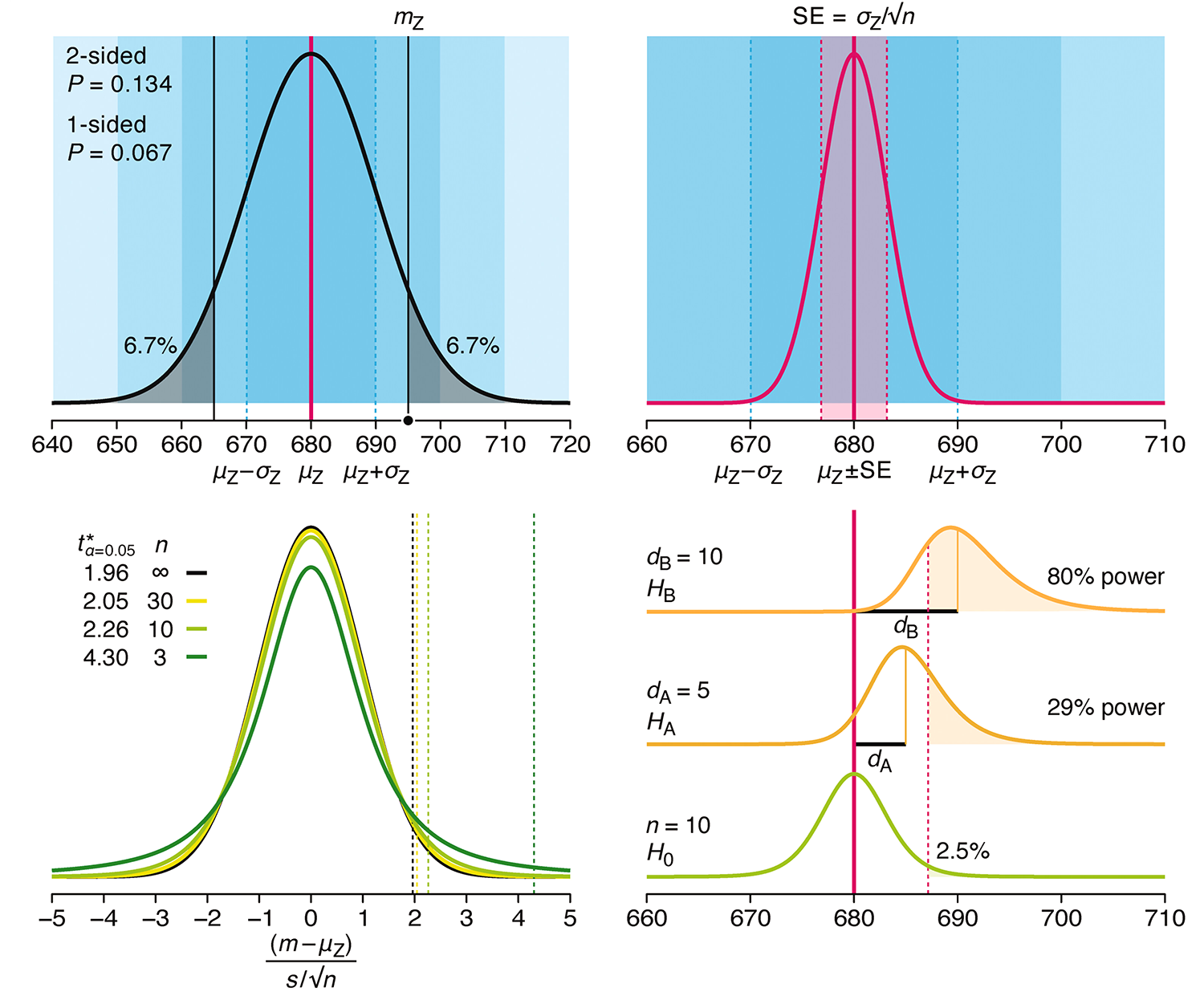

Points of Significance is an ongoing series of short articles about statistics in Nature Methods that started in 2013. Its aim is to provide clear explanations of essential concepts in statistics for a nonspecialist audience. The articles favor heuristic explanations and make extensive use of simulated examples and graphical explanations, while maintaining mathematical rigor.

Topics range from basic, but often misunderstood, such as uncertainty and P-values, to relatively advanced, but often neglected, such as the error-in-variables problem and the curse of dimensionality. More recent articles have focused on timely topics such as modeling of epidemics, machine learning, and neural networks.

In this article, we discuss the evolution of topics and details behind some of the story arcs, our approach to crafting statistical explanations and narratives, and our use of figures and numerical simulations as props for building understanding.

Altman, N. & Krzywinski, M. (2025) Crafting 10 Years of Statistics Explanations: Points of Significance. Annual Review of Statistics and Its Application 12:69–87.

Propensity score matching

I don’t have good luck in the match points. —Rafael Nadal, Spanish tennis player

In many experimental designs, we need to keep in mind the possibility of confounding variables, which may give rise to bias in the estimate of the treatment effect.

If the control and experimental groups aren't matched (or, roughly, similar enough), this bias can arise.

Sometimes this can be dealt with by randomizing, which on average can balance this effect out. When randomization is not possible, propensity score matching is an excellent strategy to match control and experimental groups.

Kurz, C.F., Krzywinski, M. & Altman, N. (2024) Points of significance: Propensity score matching. Nat. Methods 21:1770–1772.

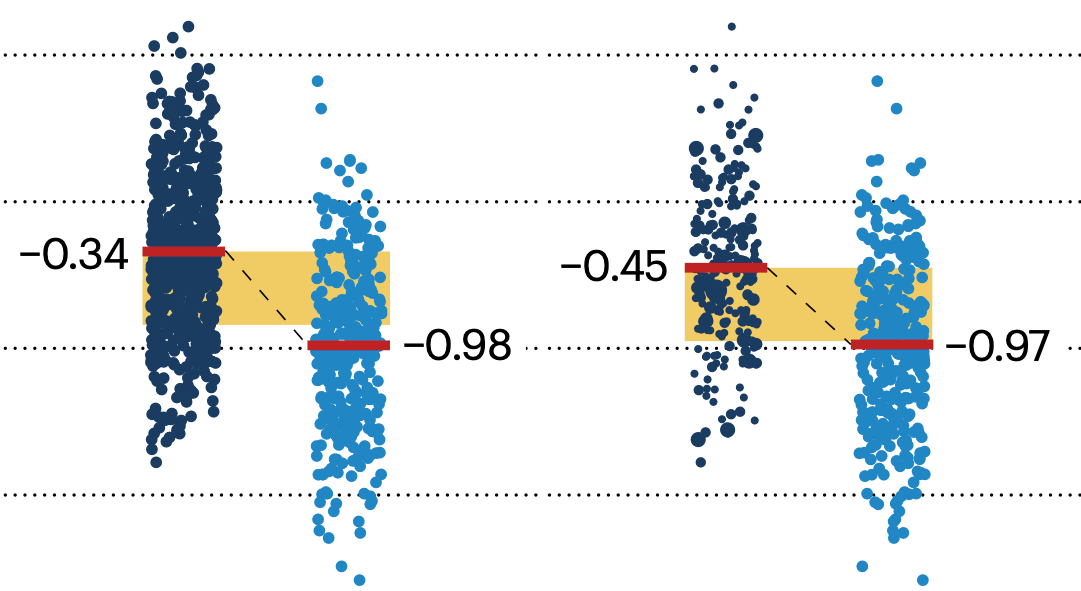

Understanding p-values and significance

P-values combined with estimates of effect size are used to assess the importance of experimental results. However, their interpretation can be invalidated by selection bias when testing multiple hypotheses, fitting multiple models or even informally selecting results that seem interesting after observing the data.

We offer an introduction to principled uses of p-values (targeted at the non-specialist) and identify questionable practices to be avoided.

Altman, N. & Krzywinski, M. (2024) Understanding p-values and significance. Laboratory Animals 58:443–446.