buy artwork

buy artwork

`\pi` Day 2014 Art Posters

On March 14th celebrate `\pi` Day. Hug `\pi`—find a way to do it.

For those who favour `\tau=2\pi` will have to postpone celebrations until July 26th. That's what you get for thinking that `\pi` is wrong. I sympathize with this position and have `\tau` day art too!

If you're not into details, you may opt to party on July 22nd, which is `\pi` approximation day (`\pi` ≈ 22/7). It's 20% more accurate that the official `\pi` day!

Finally, if you believe that `\pi = 3`, you should read why `\pi` is not equal to 3.

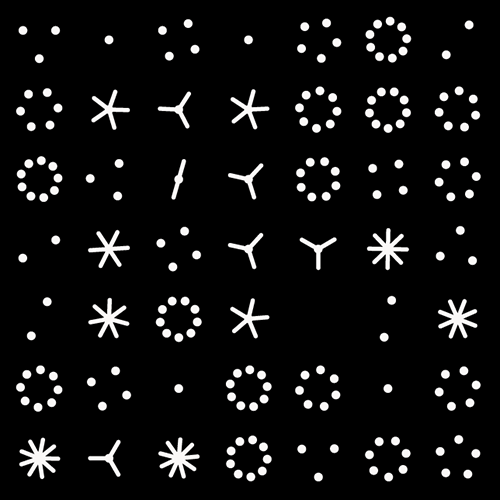

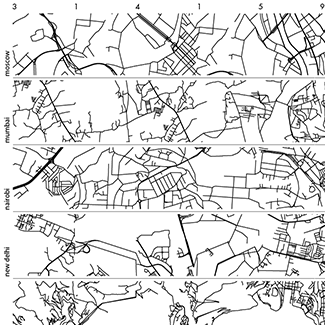

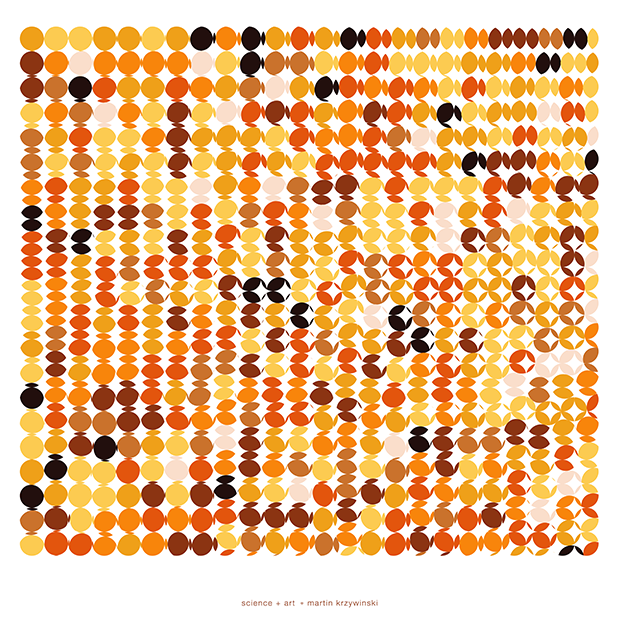

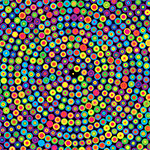

For the 2014 `\pi` day, two styles of posters are available: folded paths and frequency circles.

The folded paths show `\pi` on a path that maximizes adjacent prime digits and were created using a protein-folding algorithm.

The frequency circles colourfully depict the ratio of digits in groupings of 3 or 6. Oh, look, there's the Feynman Point!

Explore the Feynman Point and other such artefacts in `\pi` using René Hansen's interactive version of this year's posters.

The Feynman Point

The Feynman Point is the first place where 6 9s occur in π . This happens at digit 762, which is much sooner than expected. Here is π to 1,000 decimal places showing the location of the Feynman point.

3.1415926535 8979323846 2643383279 5028841971 6939937510 : 50

5820974944 5923078164 0628620899 8628034825 3421170679 : 100

8214808651 3282306647 0938446095 5058223172 5359408128 : 150

4811174502 8410270193 8521105559 6446229489 5493038196 : 200

4428810975 6659334461 2847564823 3786783165 2712019091 : 250

4564856692 3460348610 4543266482 1339360726 0249141273 : 300

7245870066 0631558817 4881520920 9628292540 9171536436 : 350

7892590360 0113305305 4882046652 1384146951 9415116094 : 400

3305727036 5759591953 0921861173 8193261179 3105118548 : 450

0744623799 6274956735 1885752724 8912279381 8301194912 : 500

9833673362 4406566430 8602139494 6395224737 1907021798 : 550

6094370277 0539217176 2931767523 8467481846 7669405132 : 600

0005681271 4526356082 7785771342 7577896091 7363717872 : 650

1468440901 2249534301 4654958537 1050792279 6892589235 : 700

4201995611 2129021960 8640344181 5981362977 4771309960 : 750

5187072113 4999999837 2978049951 0597317328 1609631859 : 800

5024459455 3469083026 4252230825 3344685035 2619311881 : 850

7101000313 7838752886 5875332083 8142061717 7669147303 : 900

5982534904 2875546873 1159562863 8823537875 9375195778 : 950

1857780532 1712268066 1300192787 6611195909 2164201989 : 1000

As the story goes, Feynman said that he'd like to memorize π up to the first 6 9s so that he could finish the recitation with "nine nine nine nine nine nine and so on". To find a scheme that suggests that π is rational is mathematical humor of the highest order.

We can ask a general question — where is the first place where digit d occurs n times? For example, where do we see the first 5555 (d=5,n=4) or 777777 (d=7,n=6) .

I look into these kinds of locations in π below. If you are interested in integer sequences in general, see the on-line encyclopedia of integer sequences (OEIS)

(d,n) points in π — sequences of repeating digits

I call a location at which digit d is seen n times in a row the (d,n) point. The Feynman point is a specific case — it is a (d=9,n=6) point.

One can talk about all the (d,n) points (i.e. (d,n,0) , (d,n,1) , (d,n,2) ...), which is the set of all locations at which d appears n times. It should be clear from the context whether one point is being referenced, or a set of points.

We can add a location index i to refer to a specific instance of the sequence. The ith appearance of the digit sequence is (d,n,i) . If we're talking about a single point and i is not specified then i=0 is assumed, which refers to the first appearance of the sequence for a given d and n. That is, (d,n) = (d,n,i=0) .

The point (d,1) trivially corresponds to the first occurence of digit d.

Below is a list of all (d,n=6,i=0) points.

d n i sequence position .....(n x d) ..... 1 6 0 111111 255945 62417(111111)75895 2 6 0 222222 963024 87437(222222)85444 4 6 0 444444 828499 02846(444444)66922 5 6 0 555555 244453 33233(555555)69581 6 6 0 666666 252499 58934(666666)88391 7 6 0 777777 399579 18074(777777)98344 8 6 0 888888 222299 10985(888888)35254 9 6 0 999999 762 21134(999999)83729 # Feynman Point

examples of (d,n) points in first 1,000,000 digits of π

There are 49 (d,n,i=0) points in the first 1,000,000 digits of π for n>1. For example, the first (d=0,n=4) , which is the first 0000, occurs at digit 13,390 (...93095000090715). The longest sequence of d=0 happens for n=7 — (d=0,n=7,i=0) is at position 710,100 (...73537333333386381).

d n i n x d position ...(n x d)... 0 2 0 00 307 24587(00)66063 1 2 0 11 94 25342(11)70679 2 2 0 22 135 55058(22)31725 3 2 0 33 24 46264(33)83279 4 2 0 44 59 09749(44)59230 5 2 0 55 130 44609(55)05822 6 2 0 66 117 28230(66)47093 7 2 0 77 559 43702(77)05392 8 2 0 88 34 79502(88)41971 9 2 0 99 44 71693(99)37510 0 3 0 000 601 05132(000)56812 1 3 0 111 153 12848(111)74502 2 3 0 222 1735 99219(222)18427 3 3 0 333 1698 39414(333)45477 4 3 0 444 2707 42858(444)79526 5 3 0 555 177 52110(555)96446 6 3 0 666 2440 49954(666)72782 7 3 0 777 4575 94764(777)26224 8 3 0 888 4985 08099(888)68741 9 3 0 999 2949 19217(999)83910 0 4 0 0000 13390 93095(0000)90715 1 4 0 1111 12700 42144(1111)26358 2 4 0 2222 4902 35136(2222)47715 3 4 0 3333 66846 31487(3333)67147 4 4 0 4444 54525 11793(4444)82014 5 4 0 5555 33172 96839(5555)68686 6 4 0 6666 21880 23047(6666)72174 7 4 0 7777 1589 28909(7777)27938 8 4 0 8888 4751 16274(8888)00786 9 4 0 9999 17988 98955(9999)11209 0 5 0 00000 17534 66768(00000)10652 1 5 0 11111 32788 46584(11111)57758 2 5 0 22222 65260 99725(22222)80801 3 5 0 33333 28467 52392(33333)64743 4 5 0 44444 808650 64849(44444)73161 5 5 0 55555 24466 89742(55555)16076 6 5 0 66666 48439 71972(66666)42267 7 5 0 77777 162248 47779(77777)18415 8 5 0 88888 213245 09581(88888)03131 9 5 0 99999 19446 21285(99999)39961 1 6 0 111111 255945 62417(111111)75895 2 6 0 222222 963024 87437(222222)85444 4 6 0 444444 828499 02846(444444)66922 5 6 0 555555 244453 33233(555555)69581 6 6 0 666666 252499 58934(666666)88391 7 6 0 777777 399579 18074(777777)98344 8 6 0 888888 222299 10985(888888)35254 9 6 0 999999 762 21134(999999)83729 3 7 0 3333333 710100 73537(3333333)86381

When we sort this list by position, we can see just how unusual (i.e. early) the Feynman Point is. We also see (d,n=2) , (d,n=3) , (d,n=4) and (d,n=5) points for all digits d) in the first 1,000,000 digits.

3 2 0 33 24 46264(33)83279 # first n=2 8 2 0 88 34 79502(88)41971 9 2 0 99 44 71693(99)37510 4 2 0 44 59 09749(44)59230 1 2 0 11 94 25342(11)70679 6 2 0 66 117 28230(66)47093 5 2 0 55 130 44609(55)05822 2 2 0 22 135 55058(22)31725 1 3 0 111 153 12848(111)74502 # first n=3 5 3 0 555 177 52110(555)96446 0 2 0 00 307 24587(00)66063 7 2 0 77 559 43702(77)05392 # last n=2 0 3 0 000 601 05132(000)56812 9 6 0 999999 762 21134(999999)83729 # first n=6 (Feynman Point) 7 4 0 7777 1589 28909(7777)27938 # first n=4 3 3 0 333 1698 39414(333)45477 2 3 0 222 1735 99219(222)18427 6 3 0 666 2440 49954(666)72782 4 3 0 444 2707 42858(444)79526 9 3 0 999 2949 19217(999)83910 7 3 0 777 4575 94764(777)26224 8 4 0 8888 4751 16274(8888)00786 2 4 0 2222 4902 35136(2222)47715 8 3 0 888 4985 08099(888)68741 # last n=3 1 4 0 1111 12700 42144(1111)26358 0 4 0 0000 13390 93095(0000)90715 0 5 0 00000 17534 66768(00000)10652 # first n=5 9 4 0 9999 17988 98955(9999)11209 9 5 0 99999 19446 21285(99999)39961 6 4 0 6666 21880 23047(6666)72174 5 5 0 55555 24466 89742(55555)16076 3 5 0 33333 28467 52392(33333)64743 1 5 0 11111 32788 46584(11111)57758 5 4 0 5555 33172 96839(5555)68686 6 5 0 66666 48439 71972(66666)42267 4 4 0 4444 54525 11793(4444)82014 2 5 0 22222 65260 99725(22222)80801 3 4 0 3333 66846 31487(3333)67147 # last n=4 7 5 0 77777 162248 47779(77777)18415 8 5 0 88888 213245 09581(88888)03131 8 6 0 888888 222299 10985(888888)35254 5 6 0 555555 244453 33233(555555)69581 6 6 0 666666 252499 58934(666666)88391 1 6 0 111111 255945 62417(111111)75895 7 6 0 777777 399579 18074(777777)98344 3 7 0 3333333 710100 73537(3333333)86381 # first n=7 4 5 0 44444 808650 64849(44444)73161 # last n=5 4 6 0 444444 828499 02846(444444)66922 2 6 0 222222 963024 87437(222222)85444

when do we expect (d,n) points?

Any given position in π , 10n different combinations of n digits can appear. In only one of them are all the digits the same and equal to d. Thus, the chance of seeing (d,n) at any position for any given d is p=10–n.

The probability of not seeing a (d,n) point at a location for a given d is 1-p.

Thus the probability of not seeing a point at k locations and then seeing one at k+1 location is (1-p)kp. This is the definition of the geometric distribution.

For example, the question "how many times must we throw a die until a 1 appears?" can be addressed by this distribution. Here p=1/6, assuming the die is fair. The probability of seeing a 1 for the first time on the k toss is

k P(X=k) 1 16.7% = (1-1/6)0 * 1/6 2 13.8% = (1-1/6)1 * 1/6 3 11.6% = (1-1/6)2 * 1/6 4 9.6% = (1-1/6)3 * 1/6 5 6.7% = (1-1/6)4 * 1/6 6 5.6% = (1-1/6)5 * 1/6 ...

The cumulative probability P(X≤k) gives us the chance of seeing a 1 for the first time on the 1, 2, 3 ... or k toss). 1-P(X≤k) is the chance of not seeing a 1 in the first 1, 2, 3 ... k tosses.

k P(X≤k) 1-P(X≤k) 1 16.7% 83.3% 2 30.6% 69.4% 3 42.1% 57.9% 4 51.8% 48.2% 5 59.8% 40.2% 6 66.5% 33.5% ...

We can apply this calculation to the probability of observing a (d,n) point for the first time. Let's pick (d=9,n=6) . Using p=10–6, let's look at 1-P(X≤k). Values in the table below for P are shown to one significant digit, except for the Feynman Point position k=962.

k P(X≤k) 1-P(X≤k) 1 0.000001 0.999999 10 0.00001 0.99999 100 0.0001 0.9999 962 0.000962 0.999037 1000 0.001 0.999 10000 0.01 0.99 100000 0.1 0.9 693147 0.5 0.5

Now we know just how unlikely the Feynman Point is. The chance of observing 6 9s in the first 962 digits is about 0.000962.

These probabilities are approximate because probability that a sequence of n digits appears at any given position is correlated across a window of n-1 digits. For example if we see (d=9,6) at position j then the probability of seeing (d=9,6) at position j+1 is 1/10, not 10–6, because we are guaranteed the first 5 9s.

all (d,n) points in 268 million digits of π

If you're interested in more (d,n) points, I calculated all for lengths n≥3 for the first ~268 million digits of π — you can download the complete list of the 2.42 million (d,n) points.

Most of these points are (d,n=3) (2.17 million). The count as function of n is

n number of (d,n) points 3 2174839 4 217431 5 21749 6 2153 7 204 8 19 9 3

The Feynman Point is (d=9,n=6,i=0) . With 268 million digits, we can find up to (d=9,n=8,i=0) — the first places in which 8 9's appear in a row. All the (d=9,n,i=9) points in the first 268 million digits of π are

9 3 0 999 2949 19217(999)83910 9 4 0 9999 17988 98955(9999)11209 9 5 0 99999 19446 21285(99999)39961 9 6 0 999999 762 21134(999999)83729 9 7 0 9999999 1722776 09713(9999999)31766 9 8 0 99999999 36356642 15746(99999999)54228

The longest sequences are for n=8 and 9, of which there are 50. We see a (d,n=8,0) point for all d.

0 8 0 00000000 172330850 65581(00000000)12202 0 8 1 00000000 184688988 50614(00000000)27944 1 8 0 11111111 159090113 46225(11111111)09751 1 8 1 11111111 174624972 36529(11111111)76023 1 8 2 11111111 199394968 58734(11111111)25842 2 8 0 22222222 175820910 95134(22222222)07695 3 8 0 33333333 36488176 81791(33333333)25108 3 8 1 33333333 248922246 51334(33333333)47253 4 8 0 44444444 22931745 74369(44444444)36403 4 8 1 44444444 65122865 35213(44444444)82112 4 8 2 44444444 221749424 95631(44444444)79916 5 8 0 55555555 168743355 75041(55555555)01882 6 8 0 66666666 55616210 64263(66666666)81935 6 8 1 66666666 129423072 80429(66666666)81580 6 8 2 66666666 160301327 23994(66666666)89064 7 8 0 77777777 82144203 84454(77777777)83966 8 8 0 88888888 239798471 04446(88888888)16169 9 8 0 99999999 36356642 15746(99999999)54228 9 8 1 99999999 66780105 26137(99999999)31798 6 9 0 666666666 45681781 79094(666666666)71734 7 9 0 777777777 24658601 85304(777777777)24846 8 9 0 888888888 46663520 87842(888888888)07509

subsequences of π in 268 million digits of π

Finally, it's interesting to see where subsequences of π occurs in π . Because π is random and non-terminating, it has infinitely many subsequences of itself in it — this is hard to think about.

In the first 268 million digits of π you see subsequences up to 8 digits, not counting the trivial one that starts at zero.

3 1 0 9 59265(3)58979

31 2 0 137 05822(31)72535

314 3 0 2120 96514(314)29809

3141 4 0 3496 67110(3141)26711

31415 5 0 88008 96265(31415)14138

314159 6 0 176451 24573(314159)78761

3141592 7 0 25198140 60173(3141592)14513

31415926 8 0 50366472 17005(31415926)09521

We can also find e (2.718281828) up to 9 digits in the first 268 digits of π .

2 1 0 6 14159(2)65358

27 2 0 28 43383(27)95028

271 3 0 241 83165(271)20190

2718 4 0 11706 24322(2718)85159

27182 5 0 28024 10077(27182)71874

271828 6 0 33789 50445(271828)92749

2718281 7 0 1526800 07421(2718281)53375

27182818 8 0 73154827 92454(27182818)56113

271828182 9 0 246890641 99305(271828182)91617

as well as φ (1.618033989) up to 8 digits,

1 1 0 1 3(1)41592

16 2 0 40 84197(16)93993

161 3 0 1610 70600(161)45249

1618 4 0 6004 60290(1618)76679

16180 5 0 105857 23121(16180)99462

161803 6 0 144979 54397(161803)03956

1618033 7 0 1205122 51502(1618033)21817

16180339 8 0 19445230 33490(16180339)99933

as well as 1/ φ = 1– φ up to 6 digits.

0 1 0 32 32795(0)28841

06 2 0 71 78164(06)28620

061 3 0 885 38142(061)71776

0618 4 0 14423 26086(0618)72455

06180 5 0 84671 08181(06180)21002

061803 6 0 933127 07779(061803)00371

0618033 7 0 12074179 53993(0618033)75138

06180339 8 0 200380161 62492(06180339)55938

Propensity score weighting

The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few. —Mr. Spock (Star Trek II)

This month, we explore a related and powerful technique to address bias: propensity score weighting (PSW), which applies weights to each subject instead of matching (or discarding) them.

Kurz, C.F., Krzywinski, M. & Altman, N. (2025) Points of significance: Propensity score weighting. Nat. Methods 22:1–3.

Happy 2025 π Day—

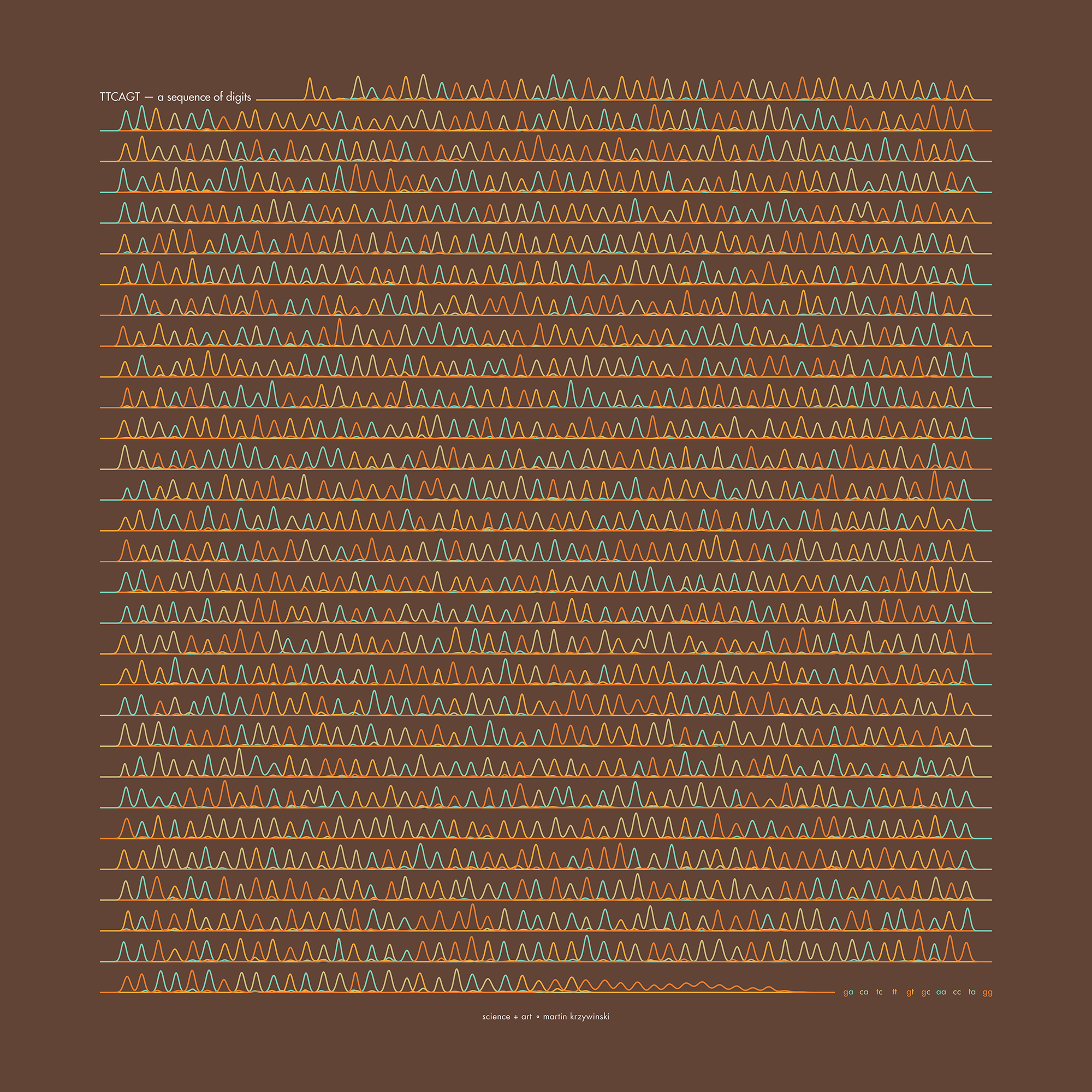

TTCAGT: a sequence of digits

Celebrate π Day (March 14th) and sequence digits like its 1999. Let's call some peaks.

Crafting 10 Years of Statistics Explanations: Points of Significance

I don’t have good luck in the match points. —Rafael Nadal, Spanish tennis player

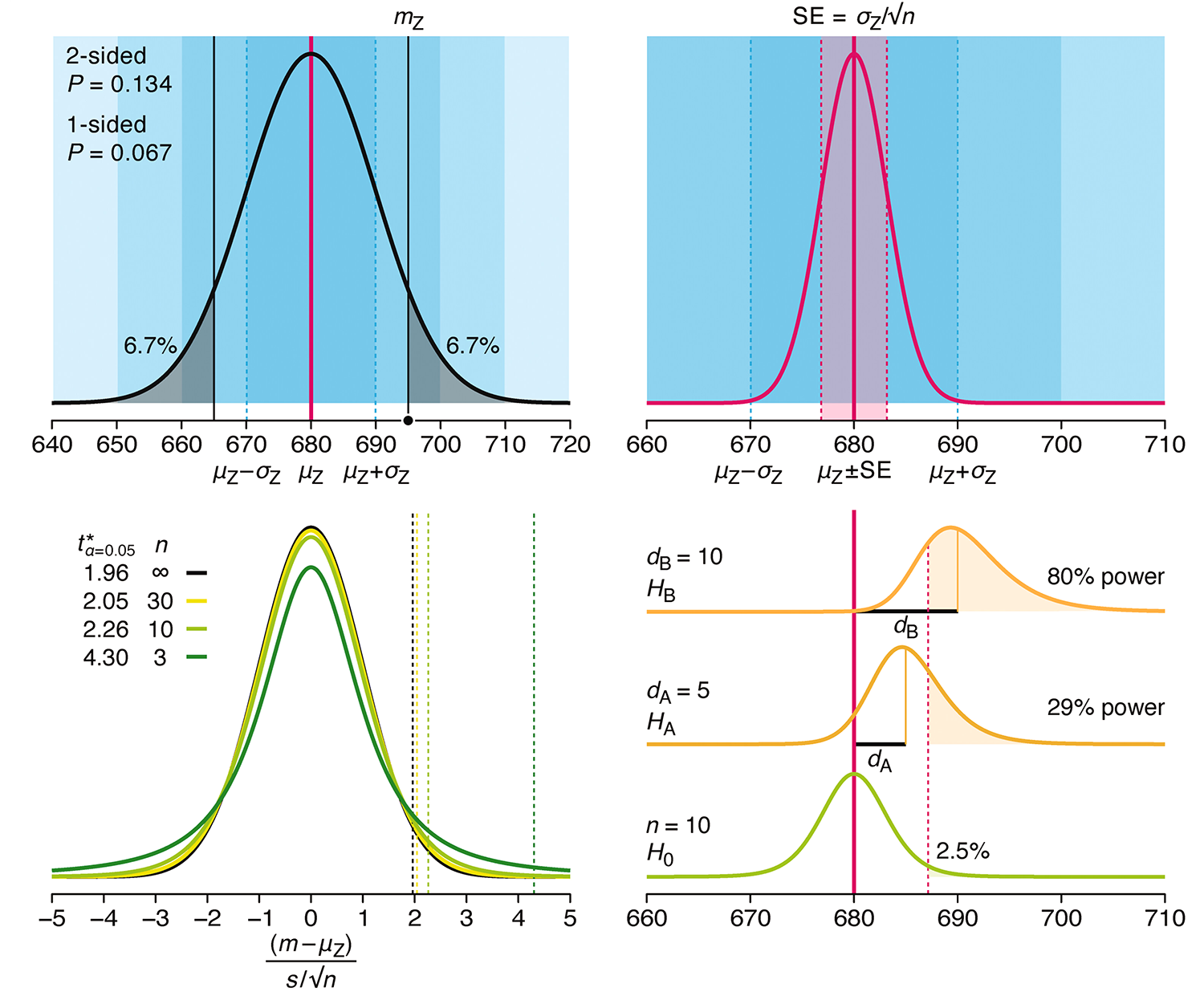

Points of Significance is an ongoing series of short articles about statistics in Nature Methods that started in 2013. Its aim is to provide clear explanations of essential concepts in statistics for a nonspecialist audience. The articles favor heuristic explanations and make extensive use of simulated examples and graphical explanations, while maintaining mathematical rigor.

Topics range from basic, but often misunderstood, such as uncertainty and P-values, to relatively advanced, but often neglected, such as the error-in-variables problem and the curse of dimensionality. More recent articles have focused on timely topics such as modeling of epidemics, machine learning, and neural networks.

In this article, we discuss the evolution of topics and details behind some of the story arcs, our approach to crafting statistical explanations and narratives, and our use of figures and numerical simulations as props for building understanding.

Altman, N. & Krzywinski, M. (2025) Crafting 10 Years of Statistics Explanations: Points of Significance. Annual Review of Statistics and Its Application 12:69–87.

Propensity score matching

I don’t have good luck in the match points. —Rafael Nadal, Spanish tennis player

In many experimental designs, we need to keep in mind the possibility of confounding variables, which may give rise to bias in the estimate of the treatment effect.

If the control and experimental groups aren't matched (or, roughly, similar enough), this bias can arise.

Sometimes this can be dealt with by randomizing, which on average can balance this effect out. When randomization is not possible, propensity score matching is an excellent strategy to match control and experimental groups.

Kurz, C.F., Krzywinski, M. & Altman, N. (2024) Points of significance: Propensity score matching. Nat. Methods 21:1770–1772.

Understanding p-values and significance

P-values combined with estimates of effect size are used to assess the importance of experimental results. However, their interpretation can be invalidated by selection bias when testing multiple hypotheses, fitting multiple models or even informally selecting results that seem interesting after observing the data.

We offer an introduction to principled uses of p-values (targeted at the non-specialist) and identify questionable practices to be avoided.

Altman, N. & Krzywinski, M. (2024) Understanding p-values and significance. Laboratory Animals 58:443–446.

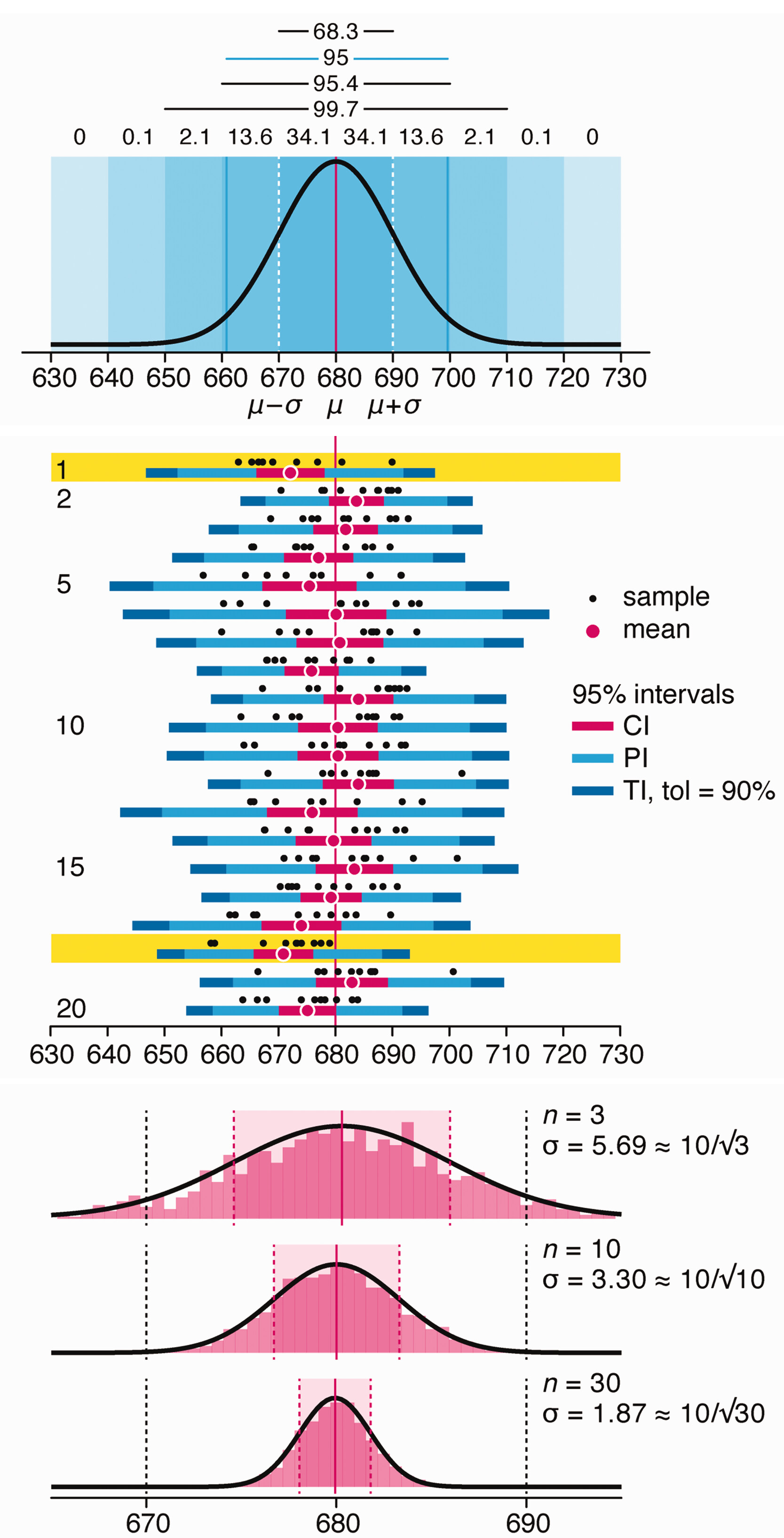

Depicting variability and uncertainty using intervals and error bars

Variability is inherent in most biological systems due to differences among members of the population. Two types of variation are commonly observed in studies: differences among samples and the “error” in estimating a population parameter (e.g. mean) from a sample. While these concepts are fundamentally very different, the associated variation is often expressed using similar notation—an interval that represents a range of values with a lower and upper bound.

In this article we discuss how common intervals are used (and misused).

Altman, N. & Krzywinski, M. (2024) Depicting variability and uncertainty using intervals and error bars. Laboratory Animals 58:453–456.