There is no sound in space, but there is music (and genomes)

Moon above

All the secrets I've told

When we're alone

Down here

I'm always lonely

When you're gone

— Down Here / Moon Above, Flunk (History of Everything Ever)

Why don't we send this music to space? What do you say?

imagination in space

Flunk has always had a special place in my heart. When I became involved in the Sanctuary Project — a kind of love letter to the Universe — I saw a way to say thank you to by favourite band.

So I invited them to come with me to somewhere distant and cold.

contents

The Sanctuary Project is a Lunar vault for humanity, inspired by projects like the Golden Record and engraved on ten 10 cm sapphire discs. The discs include math, science, maps, poetry, art and a couple of jokes.

Oh, and a backup of our species. Push to reboot.

A couple of years ago, I reached out to Ulf Nygaard, the principal and founder of Flunk, and invited him to contribute a song to Sanctuary. Something that would sound great on the Moon.

“I'll make something perfect”, he said.

And then he did.

I sat down for drinks with Flunk in Oslo. We celebrated Hitchmas. Make it a double — we were going to go to the Moon.

“Ulf, why is this album called Chemistry and Math?” I asked about Flunk's latest album at the time. And perhaps one with the most unusual title.

I will never forget his answer.

“Sitting in a cafe, I saw two people crossing the street from opposite sides. As they passed each other in the middle, they recognized each other and started talking.”

“In the end, it's just chemistry and math.”

To me, this was the Mariana trench of deep romantic statments. I knew then Flunk was the perfect match for this project.

Ok, I knew thew before too.

On May 28th, Flunk released their new album History of Everything Every and Track 1 is Down Here / Moon Above.

While the original plan was for the song to make it to the Moon before its debut on Earth, this didn't quite happen. We're still working on the Moon angle.

Yes, I do science and make art and I love Flunk, but what does all this have to do with me.

Well, four of the Sanctuary discs contain the backup for humanity: fully sequenced genomes of a woman and man. The individuals were randomly and anonymously selected from our Healthy Aging Study lead by Dr. Angela Brooks-Wilson. The DNA was sequenced at Canada's Michael Smith Genome Sciences Center.

I designed and created the content for these discs, which not only include the genomes but also the proteome (gene protein sequences) and the chemical structures of associated metabolites. The genomes include about 10 million SNPs to represent all our variation (imagine me waving my hands around at this point). The SNPs are encoded inline with the sequence, so you do not actually know what the original sequenced genome was — at each position of variation you have a choice of bases.

The discs also contain art and snippes of culture (some pop and some not). It's basically a giant cosmic Easter egg.

Each disc is a 10 cm diameter sapphire wafer containing 3 billion 1-bit pixels.

They're thermodynamically inert and will last forever. Roughly speaking.

You can pixel-peep and browse each of the discs.

To me, these discs are a love poem to the Universe. Or a post card — I love post cards.

The four genome discs look like this.

You know you're done reading when you get to the end.

The first disc, which contains roughly the first half of the female genome, also contains instructions for decoding, along with a few of our learned lessons (Nuremberg Code and Declaration of Helsinki) that remind the reader not to experiment carelessly with the information.

Peeping a bit closer, these instructions take shape. the long black strip is a spectrogram encoding of Flunk's song. For a closeup of the decoding instructions for the discs, see the Instructions section.

music for space

Flunk's song is encoded using 128 mel 3-bit spectrogram. This takes 11,688 × 384 1-bit pixels on the discs. For details see the Sonogram section.

poster for space

A 512 mel 1-bit encoding of the full History of Everything Ever album. Great for your wall or Moon patch.

Beyond Belief Campaign BRCA Art

Fuelled by philanthropy, findings into the workings of BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes have led to groundbreaking research and lifesaving innovations to care for families facing cancer.

This set of 100 one-of-a-kind prints explore the structure of these genes. Each artwork is unique — if you put them all together, you get the full sequence of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 proteins.

Propensity score weighting

The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few. —Mr. Spock (Star Trek II)

This month, we explore a related and powerful technique to address bias: propensity score weighting (PSW), which applies weights to each subject instead of matching (or discarding) them.

Kurz, C.F., Krzywinski, M. & Altman, N. (2025) Points of significance: Propensity score weighting. Nat. Methods 22:1–3.

Happy 2025 π Day—

TTCAGT: a sequence of digits

Celebrate π Day (March 14th) and sequence digits like its 1999. Let's call some peaks.

Crafting 10 Years of Statistics Explanations: Points of Significance

I don’t have good luck in the match points. —Rafael Nadal, Spanish tennis player

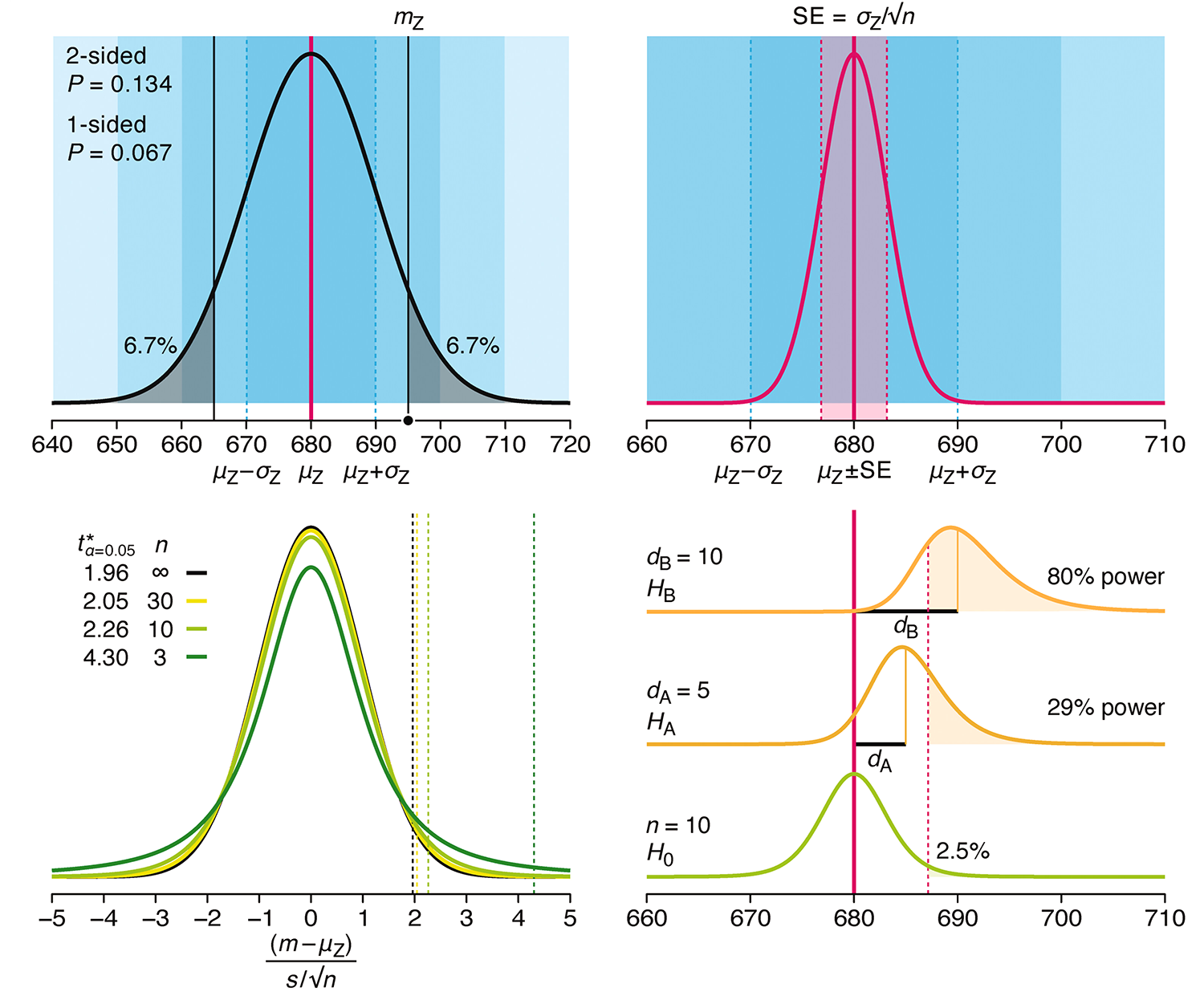

Points of Significance is an ongoing series of short articles about statistics in Nature Methods that started in 2013. Its aim is to provide clear explanations of essential concepts in statistics for a nonspecialist audience. The articles favor heuristic explanations and make extensive use of simulated examples and graphical explanations, while maintaining mathematical rigor.

Topics range from basic, but often misunderstood, such as uncertainty and P-values, to relatively advanced, but often neglected, such as the error-in-variables problem and the curse of dimensionality. More recent articles have focused on timely topics such as modeling of epidemics, machine learning, and neural networks.

In this article, we discuss the evolution of topics and details behind some of the story arcs, our approach to crafting statistical explanations and narratives, and our use of figures and numerical simulations as props for building understanding.

Altman, N. & Krzywinski, M. (2025) Crafting 10 Years of Statistics Explanations: Points of Significance. Annual Review of Statistics and Its Application 12:69–87.

Propensity score matching

I don’t have good luck in the match points. —Rafael Nadal, Spanish tennis player

In many experimental designs, we need to keep in mind the possibility of confounding variables, which may give rise to bias in the estimate of the treatment effect.

If the control and experimental groups aren't matched (or, roughly, similar enough), this bias can arise.

Sometimes this can be dealt with by randomizing, which on average can balance this effect out. When randomization is not possible, propensity score matching is an excellent strategy to match control and experimental groups.

Kurz, C.F., Krzywinski, M. & Altman, N. (2024) Points of significance: Propensity score matching. Nat. Methods 21:1770–1772.

Understanding p-values and significance

P-values combined with estimates of effect size are used to assess the importance of experimental results. However, their interpretation can be invalidated by selection bias when testing multiple hypotheses, fitting multiple models or even informally selecting results that seem interesting after observing the data.

We offer an introduction to principled uses of p-values (targeted at the non-specialist) and identify questionable practices to be avoided.

Altman, N. & Krzywinski, M. (2024) Understanding p-values and significance. Laboratory Animals 58:443–446.