BD Genomics stereoscopic art exhibit — AGBT 2017

Art is science in love.

— E.F. Weisslitz

contents

Science cannot move forward without storytelling. While we learn about the world and its patterns through science, it is through stories that we can organize and sort through the observations and conclusions that drive the generation of scientific hypotheses.

With Alberto Cairo, I've written about the importance of storytelling as a tool to explain and narrate in Storytelling (2013) Nat. Methods 10:687. There we suggest that instead of "explain, not merely show," you should seek to "narrate, not merely explain."

Our account received support (Should scientists tell stories. (2013) Nat. Methods 10:1037) but not from all (Against storytelling of scientific results. (2013) Nat. Methods 10:1045).

A good science story must present facts and conclusions within a hierarchy—a bag of unsorted observations isn't likely to engage your readers. But while a story must always inform, it should also delight (as much as possible), and inspire. It should make the complexity of the problem accessible—or, at least, approachable—without simplifications that preclude insight into how concepts connect (they always do).

Just like science, explaining science is a process—one that can be more vexing than the science itself!

In science one tries to tell people, in such a way as to be understood by everyone, something that no one ever knew before. But in poetry, it’s the exact opposite.

—Paul Dirac, Mathematical Circles Adieu by H. Eves [quoted]

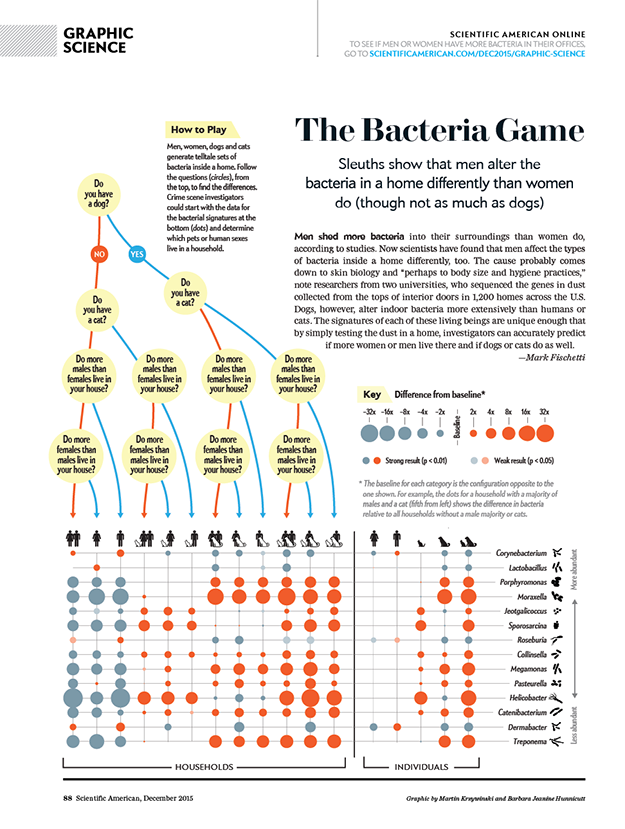

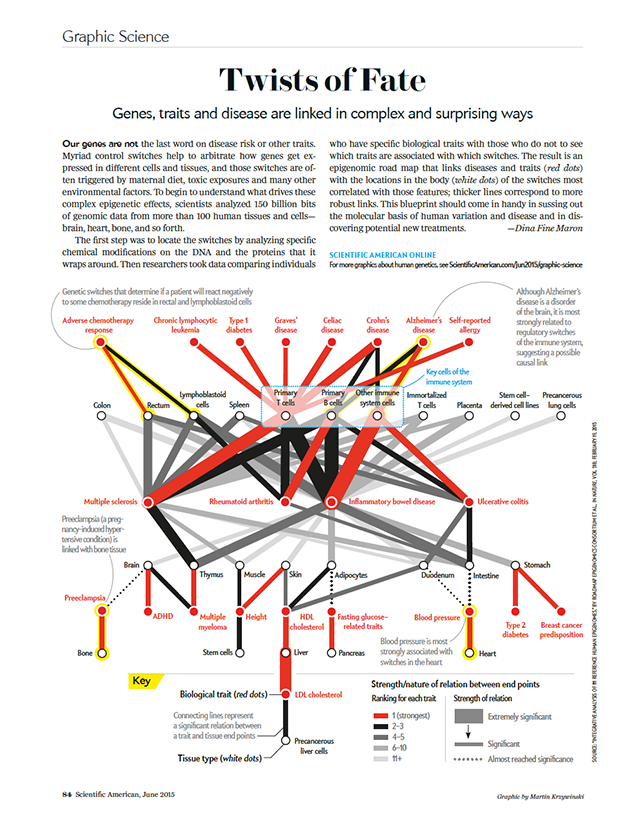

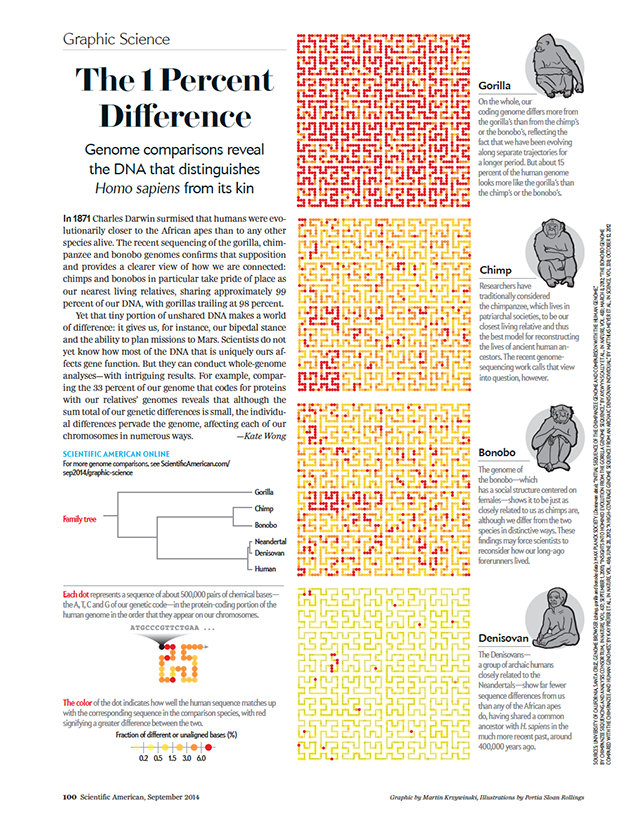

I have previously written about the process of taking a scientific statement (Creating Scientific American Graphic Science graphics) and turning it into a data visualization or, more broadly, visual story.

The process of the creation of one of these visual stories is itself a story. A story about how the genome is not a blueprint, a discovery of Hilbertonians, which are creatures that live on the Hilbert curve, how algorithms for protein folding can be used to generate art based on the digits of `\pi`, or how we can make human genome art by humans with genomes. I've also written about my design process in creating the cover for Genome Research and the cover of PNAS. As always, not everything works out all the time—read about the EMBO Journal covers that never made it.

Here, I'd like to walk you through the process and sketches of creating a story based on the idea of differences in data and how the story can be used to understand the function of cells and disease.

The visual story is a creative collaboration with Becton Dickinson and The Linus Group and its creation began with the concept of differences. The art was on display at AGBT 2017 conference and accompanies BD's launch of the Resolve platform and "Difference of One in Genomics".

Starting with the idea of the "difference of one", our goal was to create artistic representations of data sets generated using the BD Resolve platform, which generates single-cell transcriptomes, that captured a variety of differences that are relevant in genomics research.

The data art pieces were installed in a gallery style, with data visualization and artistic expression in equal parts.

The art itself is an old school take on virtual reality. Unlike modern VR, which isolates the participants from one another, we chose a low-tech route that not only brings the audience closer to the data but also to each other.

The data were generated using the BD Resolve single-cell transcriptomics platform. For each of the three art pieces, we identified a data set that captured a variety of differences.

- disease onset—how does gene expression in tumor cells differ from normal cells?

- disease progression—as a tumor grows and spreads, how does expression change?

- background variation—how does gene expression change between normal cells that perform a different function?

The real surprise and insight is in difference that ultimately advance our thinking (Data visualization: amgibuity as a fellow traveller. (2013) Nat. Methods 10:613-615).

Figuring out which differences are of this kind requires that instead of "What's new?" we ask "What's different?"

Beyond Belief Campaign BRCA Art

Fuelled by philanthropy, findings into the workings of BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes have led to groundbreaking research and lifesaving innovations to care for families facing cancer.

This set of 100 one-of-a-kind prints explore the structure of these genes. Each artwork is unique — if you put them all together, you get the full sequence of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 proteins.

Propensity score weighting

The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few. —Mr. Spock (Star Trek II)

This month, we explore a related and powerful technique to address bias: propensity score weighting (PSW), which applies weights to each subject instead of matching (or discarding) them.

Kurz, C.F., Krzywinski, M. & Altman, N. (2025) Points of significance: Propensity score weighting. Nat. Methods 22:1–3.

Happy 2025 π Day—

TTCAGT: a sequence of digits

Celebrate π Day (March 14th) and sequence digits like its 1999. Let's call some peaks.

Crafting 10 Years of Statistics Explanations: Points of Significance

I don’t have good luck in the match points. —Rafael Nadal, Spanish tennis player

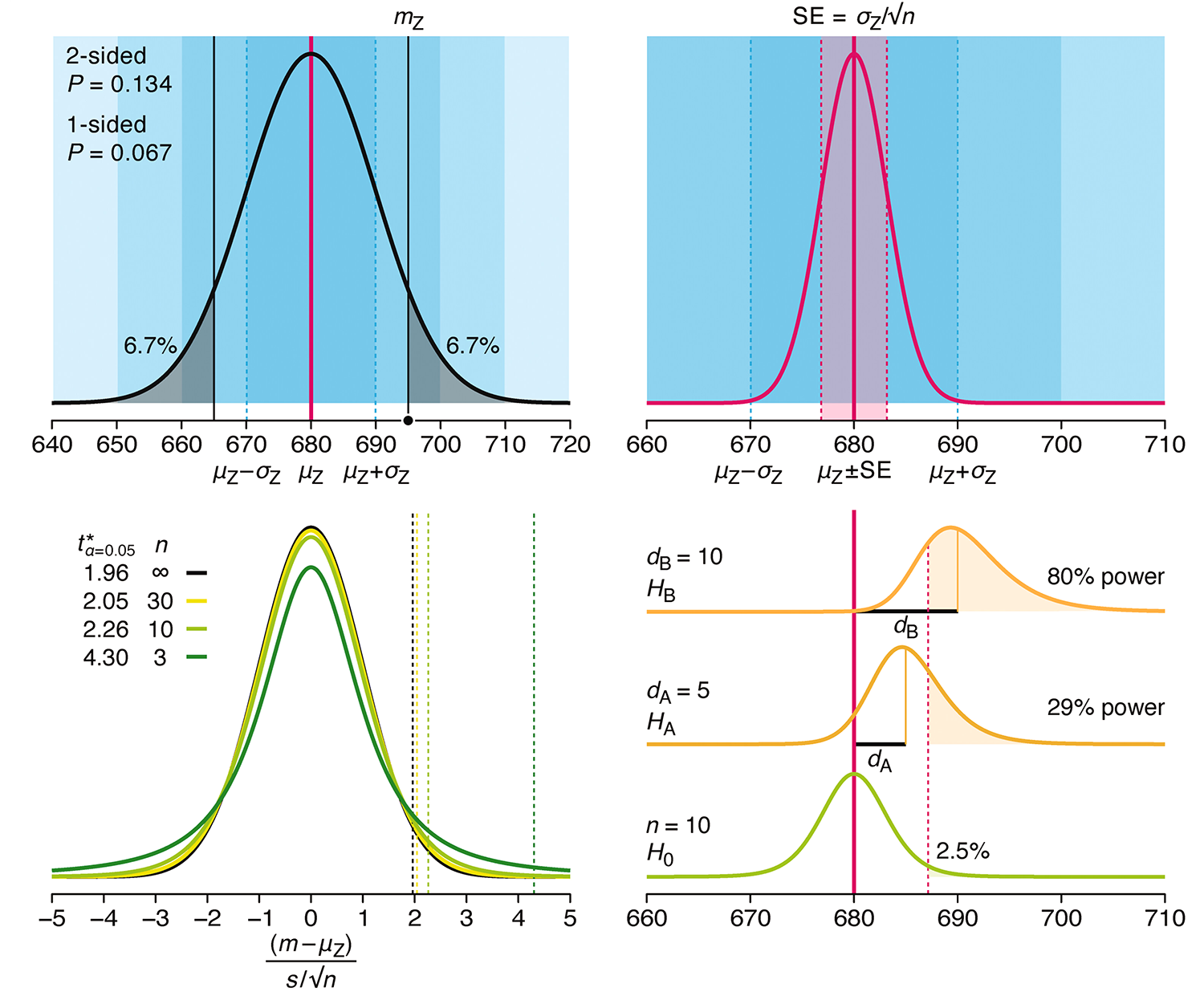

Points of Significance is an ongoing series of short articles about statistics in Nature Methods that started in 2013. Its aim is to provide clear explanations of essential concepts in statistics for a nonspecialist audience. The articles favor heuristic explanations and make extensive use of simulated examples and graphical explanations, while maintaining mathematical rigor.

Topics range from basic, but often misunderstood, such as uncertainty and P-values, to relatively advanced, but often neglected, such as the error-in-variables problem and the curse of dimensionality. More recent articles have focused on timely topics such as modeling of epidemics, machine learning, and neural networks.

In this article, we discuss the evolution of topics and details behind some of the story arcs, our approach to crafting statistical explanations and narratives, and our use of figures and numerical simulations as props for building understanding.

Altman, N. & Krzywinski, M. (2025) Crafting 10 Years of Statistics Explanations: Points of Significance. Annual Review of Statistics and Its Application 12:69–87.

Propensity score matching

I don’t have good luck in the match points. —Rafael Nadal, Spanish tennis player

In many experimental designs, we need to keep in mind the possibility of confounding variables, which may give rise to bias in the estimate of the treatment effect.

If the control and experimental groups aren't matched (or, roughly, similar enough), this bias can arise.

Sometimes this can be dealt with by randomizing, which on average can balance this effect out. When randomization is not possible, propensity score matching is an excellent strategy to match control and experimental groups.

Kurz, C.F., Krzywinski, M. & Altman, N. (2024) Points of significance: Propensity score matching. Nat. Methods 21:1770–1772.

Understanding p-values and significance

P-values combined with estimates of effect size are used to assess the importance of experimental results. However, their interpretation can be invalidated by selection bias when testing multiple hypotheses, fitting multiple models or even informally selecting results that seem interesting after observing the data.

We offer an introduction to principled uses of p-values (targeted at the non-specialist) and identify questionable practices to be avoided.

Altman, N. & Krzywinski, M. (2024) Understanding p-values and significance. Laboratory Animals 58:443–446.