Creating the Genome Research November 2012 Cover

contents

My November 2012 Genome Research cover design takes a fun and illustrative approach to visualization. It's a mix of art and science.

The cover image accompanies the article by Cydney Nielsen from our visualization group, describing her Spark tool for visualization epigenetics data.

Nielsen CB, Younesy H, O'Geen H, Xu X, Jackson AR, et al. (2012) Spark: A navigational paradigm for genomic data exploration. Genome Res 22: 2262-2269.

Instead of a literal depiction of output from Spark, the final design presents what appears to be necklaces of the kind of tiles that Spark uses for its visual presentation. I took a chance that Genome Research had a sense of humor. Luckily, they did and accepted the design for the cover.

Colored tiles are playfully suspended on vertical strings to illustrate how Spark, presented in this issue, uses clustering to group genomic regions (tiles) with similar data patterns (colored heatmaps) and facilitates genome-wide data exploration. — Genome Research 22 (11)

Browse my gallery of cover designs.

Thinking about design ideas for the cover, I looked to the kind of visual motifs that Spark used for inspiration. Immediately the colorful tiles, which represent clustered data tracks, stood out.

Spark's output is very stylized, colorful and high contrast. It was important to preserve this aesthetic in the design. I also wanted to incorporate the idea of clustering in the design, as well as the concept that the clusters represented data from different parts of the genome.

While it was not important to illustrate how Spark organizes and analyzed data explicitly — in fact, I wanted these aspects to be subtle — it was important that the cover illustration had connections to Spark at several levels.

Spark was created by Cydney Nielsen, who works with me at the Genome Sciences Center. It is designed to mitigate the difficulties arising from the fact that genome-wide data is typically scattered across thousands of points of interest.

Genome browsers integrate diverse data sets by plotting them as vertically stacked tracks across a common genomic x-axis. Genome browsers are designed for viewing local regions of interest (e.g. an individual gene) and are frequently used during the initial data inspection and exploration phases.

Most genome browsers support zooming along the genome coordinate. This type of overview is not always useful because it produces a summary across a continuous genomic range (e.g. chromosome 1) and not across the subset of regions that are of interest (e.g. genes on chromosome 1). Spark addresses this shortcoming and provides a way to help answer questions like: What are the common data patterns across genes start sites in my data set?

Spark's visualization is driven by clustering data tracks (e.g. ChIP-seq coverage) from across equivalent regions (e.g. gene start sites). The clustered tracks are displayed as heatmaps, with each row being a data track and each column a windowed region of the genome.

With fond memories of Monte Carlo simulations from my physics days, I set out to simulate some realistic-looking, but entirely synthetic, Spark cluster tiles.

My first idea was a design which would show these tiles falling, perhaps accumulating on a pile on the ground. Quick prototypes of this idea were disappointing. The tiles appeared flimsy and too complex, while the image was largely empty. I spent several hours messing around with the rotation and pseudo-3D layout, but could not find anything that was satisfying.

I thought to do this right would require a proper simulation within a 3D system.

To address the fact that the tiles felt flimsy and overly complicated and the design lacked depth, I simplified the tile simulation to generate 5x5 tiles. These simpler representations still embodied how Spark displayed data, but did so minimally.

To keep with the idea that the clusters come from different regions of the genome, I thought of arranging them along line segments. Unlike the design in which the tiles were falling, this constrained the layout significantly and allowed me to play with the design to make it look like the clusters were draped over it. By casting a light shadow behind each string of tiles, a subtle 3D effect could be achieved while still keeping the design within a plane.

There are 11 orientations of tiles created by rotating a thin square around the vertical axis with a slight forward tilt. There are 5 rotations to the left and right at angles 10, 26, 46, 66 and 80 degrees. The rotation was achieved using Illustrator's Extrude and Bevel 3D filter.

The layout and rotation of the tiles was inspired by Flight and Fall by Rachel Nottingham, a mobile of paper birds.

I wanted to keep the layout of the spark tiles pleasant, without being too organized. I find this to be a difficult balance to achieve — natural randomness is deceptively difficult to create by hand.

Four different versions of the design were submitted to Genome Research. I was happiest with the treatment in which the tiles maintained their color and the Spark clusters were projected as tones of white. This designed felt more solid and punchy — I feel like you can reach out and touch one of those strings.

Beyond Belief Campaign BRCA Art

Fuelled by philanthropy, findings into the workings of BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes have led to groundbreaking research and lifesaving innovations to care for families facing cancer.

This set of 100 one-of-a-kind prints explore the structure of these genes. Each artwork is unique — if you put them all together, you get the full sequence of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 proteins.

Propensity score weighting

The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few. —Mr. Spock (Star Trek II)

This month, we explore a related and powerful technique to address bias: propensity score weighting (PSW), which applies weights to each subject instead of matching (or discarding) them.

Kurz, C.F., Krzywinski, M. & Altman, N. (2025) Points of significance: Propensity score weighting. Nat. Methods 22:1–3.

Happy 2025 π Day—

TTCAGT: a sequence of digits

Celebrate π Day (March 14th) and sequence digits like its 1999. Let's call some peaks.

Crafting 10 Years of Statistics Explanations: Points of Significance

I don’t have good luck in the match points. —Rafael Nadal, Spanish tennis player

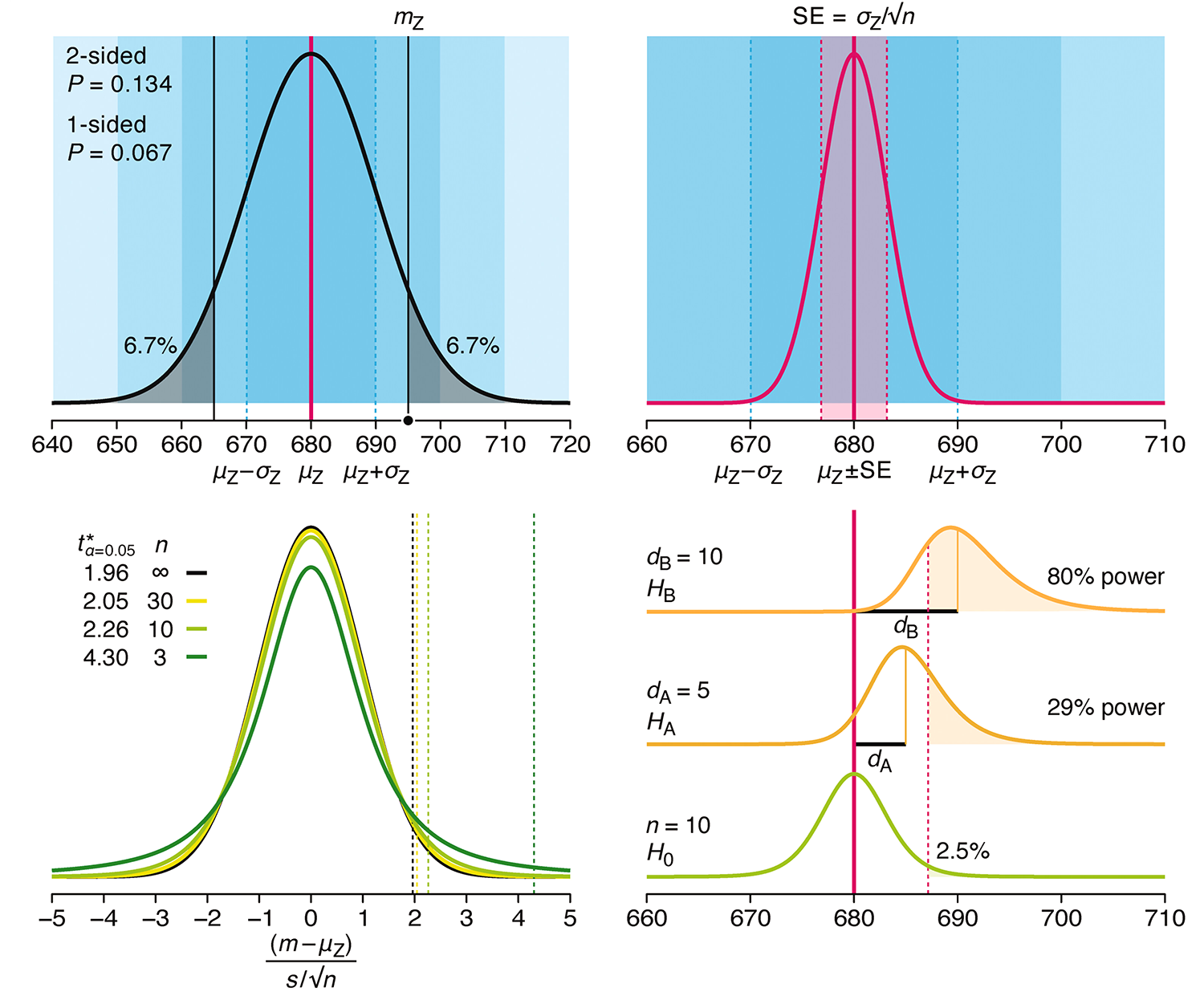

Points of Significance is an ongoing series of short articles about statistics in Nature Methods that started in 2013. Its aim is to provide clear explanations of essential concepts in statistics for a nonspecialist audience. The articles favor heuristic explanations and make extensive use of simulated examples and graphical explanations, while maintaining mathematical rigor.

Topics range from basic, but often misunderstood, such as uncertainty and P-values, to relatively advanced, but often neglected, such as the error-in-variables problem and the curse of dimensionality. More recent articles have focused on timely topics such as modeling of epidemics, machine learning, and neural networks.

In this article, we discuss the evolution of topics and details behind some of the story arcs, our approach to crafting statistical explanations and narratives, and our use of figures and numerical simulations as props for building understanding.

Altman, N. & Krzywinski, M. (2025) Crafting 10 Years of Statistics Explanations: Points of Significance. Annual Review of Statistics and Its Application 12:69–87.

Propensity score matching

I don’t have good luck in the match points. —Rafael Nadal, Spanish tennis player

In many experimental designs, we need to keep in mind the possibility of confounding variables, which may give rise to bias in the estimate of the treatment effect.

If the control and experimental groups aren't matched (or, roughly, similar enough), this bias can arise.

Sometimes this can be dealt with by randomizing, which on average can balance this effect out. When randomization is not possible, propensity score matching is an excellent strategy to match control and experimental groups.

Kurz, C.F., Krzywinski, M. & Altman, N. (2024) Points of significance: Propensity score matching. Nat. Methods 21:1770–1772.

Understanding p-values and significance

P-values combined with estimates of effect size are used to assess the importance of experimental results. However, their interpretation can be invalidated by selection bias when testing multiple hypotheses, fitting multiple models or even informally selecting results that seem interesting after observing the data.

We offer an introduction to principled uses of p-values (targeted at the non-specialist) and identify questionable practices to be avoided.

Altman, N. & Krzywinski, M. (2024) Understanding p-values and significance. Laboratory Animals 58:443–446.