Genome Informatics 2010 cover

contents

The program cover shows sequences of some of the genes and viruses that appear in the 2010 Genome Informatics conference's abstracts.

The booklet was published with a black cover background. Below is an inverted and pinkish take on the cover.

Each sequence is represented by a continuous path. The length of the path is proportional to the length of the sequence.

At each point on the path, color is used to show the GC content computed over a window of 20 bases at that position.

Because the GC content doesn't vary greatly, values in the range 0.2–0.6 are mapped onto hues 0–300, with GC values outside that range assigned to the start and end hues. To smooth the color mpaping, a running average is calculated across 10 adjacent samples.

Direction of the curvature of the path is determined by the GC content relative to the average GC content of the human genome.

The magnitude of path curvature is informed by the repeat content near that location, which is calculated by determining the average frequency of 10-mers sampled within a window of 200 bases relative to their frequency in the human exon sequence.

This quantity is expressed relative to the chance of observing these 10-mers randomly and used to inform the angle of the path. Regions that are composed of 10-mers that are relatively rare are straighter than those which contain repetitive regions.

The path is confined within a circular area to keep it compact, at the cost of losing translational and rotational invariance of the representation. This limitation is due to the fact that the segments of the path depend on the angle and position at which the path approaches the circular boundary.

For genes, the transcribed sequence is shown, which includes both introns and exons.

The overall effect of the path encoding is a qualitative, artistic interpretation of local sequence structure. Two paths can be directly compared to interrogate differences in their corresponding sequence.

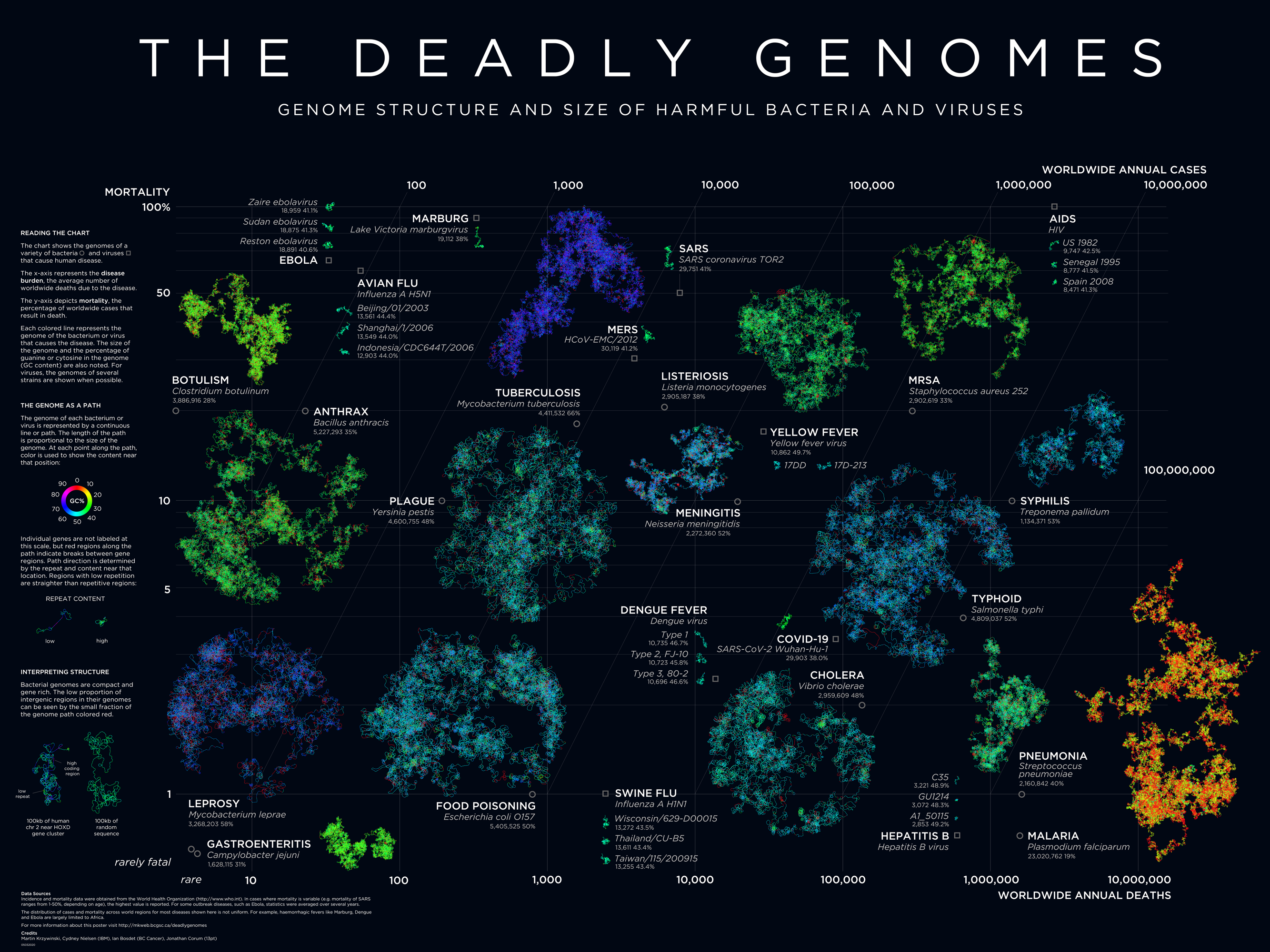

The Deadly Genomes poster demonstrates how entire genomes appear when encoded as paths. The poster compares the incidence rates and mortality of harmful viruses and bacteria, such as malaria, syphilis, AIDS and SARS.

As on the conference covers, on the poster each genome is drawn as a path. The length of the path is proportional to the size of the genome. Every fifth base is drawn as a circle whose color is based on the GC content (fraction of guanines and cytosines). The path curvature is proportional to the repeat content and the direction of curvature is determined by whether the GC content is lower or higher than average. Genomes are labeled by disease, organism, size (in bases) and GC content. Updated with the genome of SARS-CoV-2 (Wuhan-Hu-1 isolate) and COVID-19 case statistics as of 3 March 2020."

The poster was a finalist in the 2009 National Science Foundation Visualization Challenge.

Beyond Belief Campaign BRCA Art

Fuelled by philanthropy, findings into the workings of BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes have led to groundbreaking research and lifesaving innovations to care for families facing cancer.

This set of 100 one-of-a-kind prints explore the structure of these genes. Each artwork is unique — if you put them all together, you get the full sequence of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 proteins.

Propensity score weighting

The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few. —Mr. Spock (Star Trek II)

This month, we explore a related and powerful technique to address bias: propensity score weighting (PSW), which applies weights to each subject instead of matching (or discarding) them.

Kurz, C.F., Krzywinski, M. & Altman, N. (2025) Points of significance: Propensity score weighting. Nat. Methods 22:1–3.

Happy 2025 π Day—

TTCAGT: a sequence of digits

Celebrate π Day (March 14th) and sequence digits like its 1999. Let's call some peaks.

Crafting 10 Years of Statistics Explanations: Points of Significance

I don’t have good luck in the match points. —Rafael Nadal, Spanish tennis player

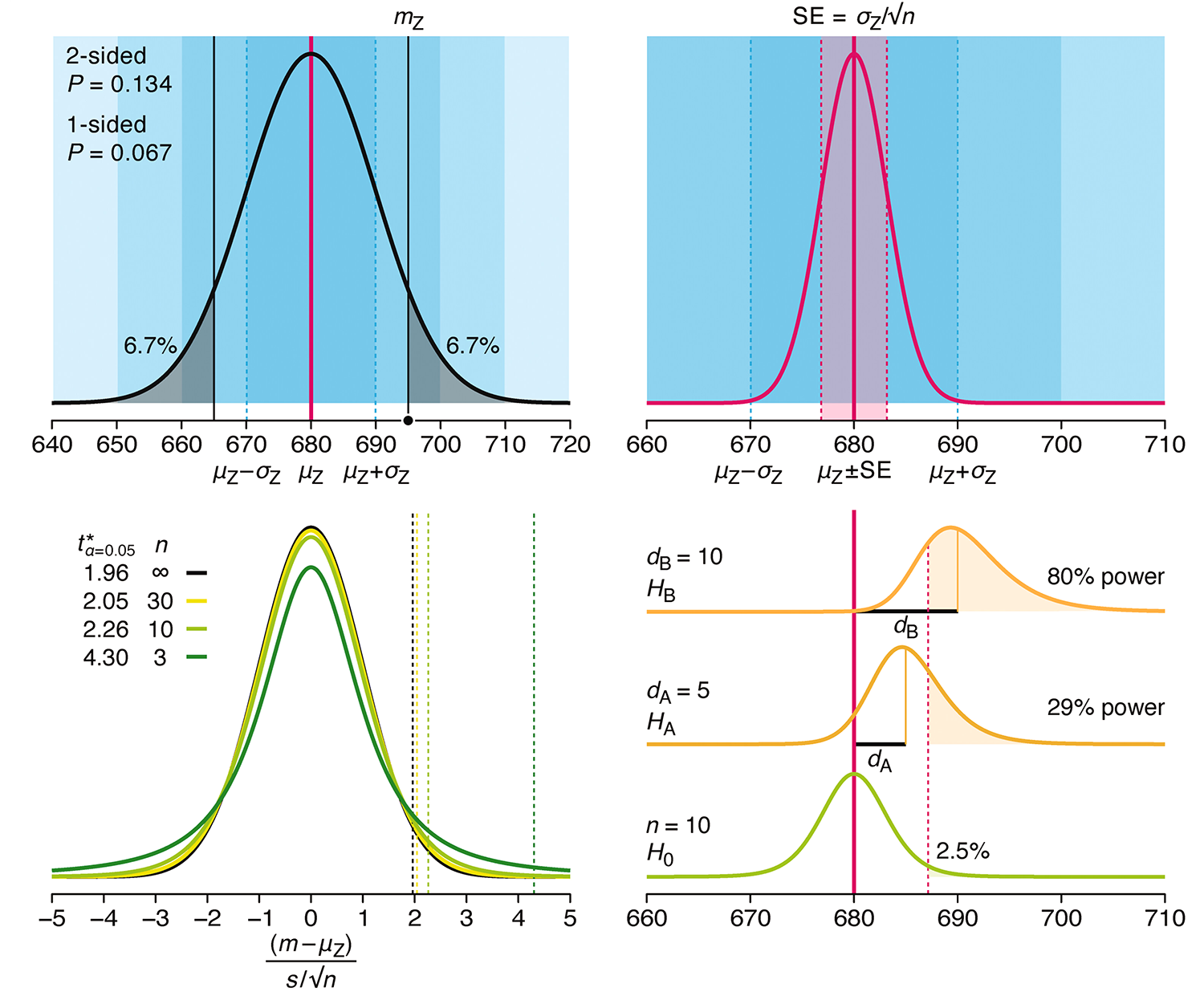

Points of Significance is an ongoing series of short articles about statistics in Nature Methods that started in 2013. Its aim is to provide clear explanations of essential concepts in statistics for a nonspecialist audience. The articles favor heuristic explanations and make extensive use of simulated examples and graphical explanations, while maintaining mathematical rigor.

Topics range from basic, but often misunderstood, such as uncertainty and P-values, to relatively advanced, but often neglected, such as the error-in-variables problem and the curse of dimensionality. More recent articles have focused on timely topics such as modeling of epidemics, machine learning, and neural networks.

In this article, we discuss the evolution of topics and details behind some of the story arcs, our approach to crafting statistical explanations and narratives, and our use of figures and numerical simulations as props for building understanding.

Altman, N. & Krzywinski, M. (2025) Crafting 10 Years of Statistics Explanations: Points of Significance. Annual Review of Statistics and Its Application 12:69–87.

Propensity score matching

I don’t have good luck in the match points. —Rafael Nadal, Spanish tennis player

In many experimental designs, we need to keep in mind the possibility of confounding variables, which may give rise to bias in the estimate of the treatment effect.

If the control and experimental groups aren't matched (or, roughly, similar enough), this bias can arise.

Sometimes this can be dealt with by randomizing, which on average can balance this effect out. When randomization is not possible, propensity score matching is an excellent strategy to match control and experimental groups.

Kurz, C.F., Krzywinski, M. & Altman, N. (2024) Points of significance: Propensity score matching. Nat. Methods 21:1770–1772.

Understanding p-values and significance

P-values combined with estimates of effect size are used to assess the importance of experimental results. However, their interpretation can be invalidated by selection bias when testing multiple hypotheses, fitting multiple models or even informally selecting results that seem interesting after observing the data.

We offer an introduction to principled uses of p-values (targeted at the non-specialist) and identify questionable practices to be avoided.

Altman, N. & Krzywinski, M. (2024) Understanding p-values and significance. Laboratory Animals 58:443–446.