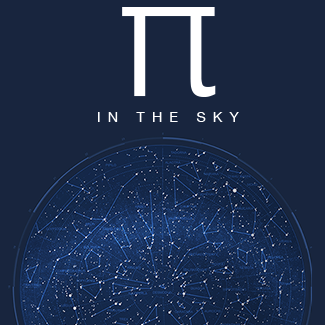

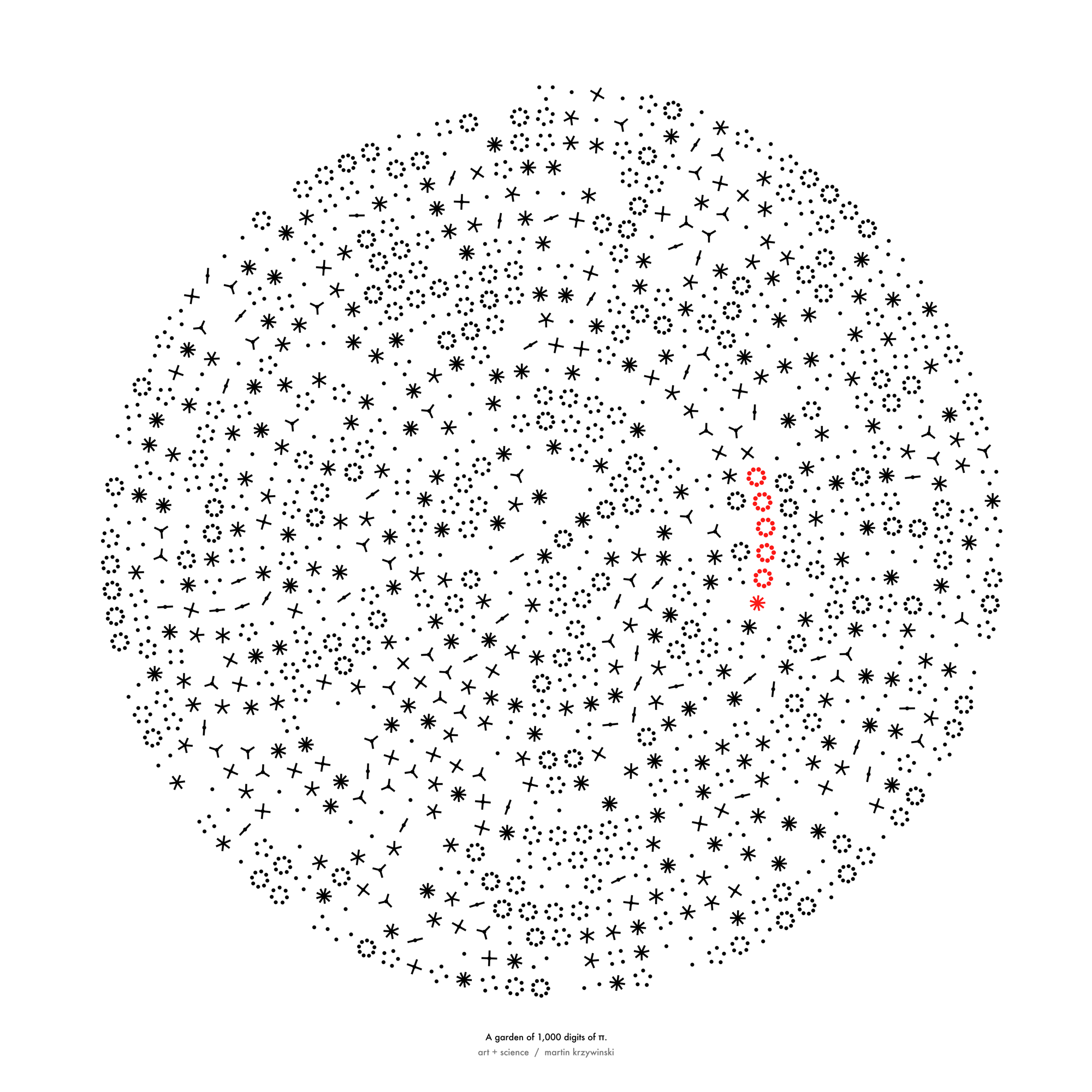

The art of Pi (`\pi`), Phi (`\phi`) and `e`

This section contains various art work based on `\pi`, `\phi` and `e` that I created over the years.

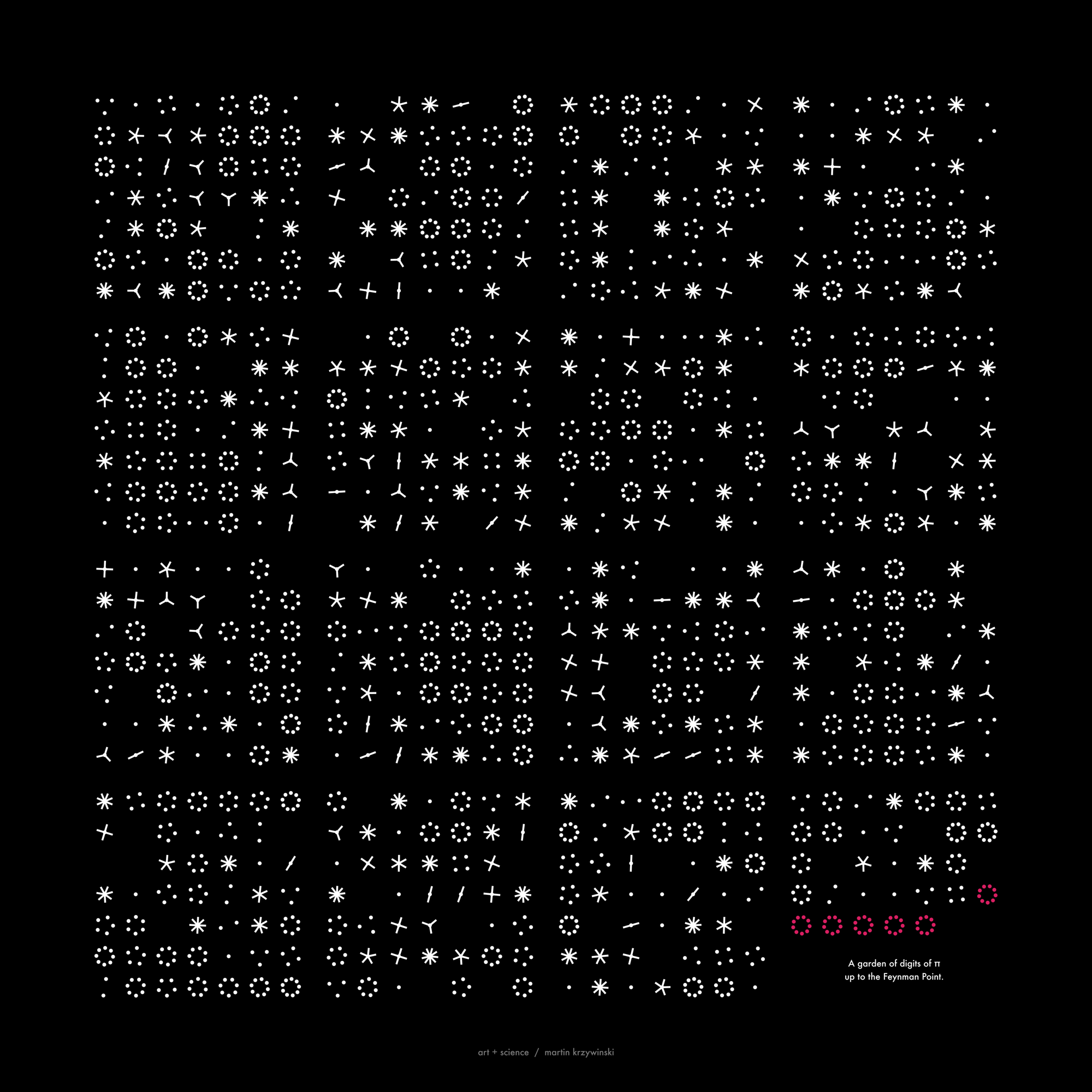

Some of the numerical art reveals interesting and unexpected observations. For example, the sequence 999999 in π at digit 762 called the Feynman Point. Or that if you calculate π to 13,099,586 digits you will find love.

`\pi` day art and `\pi` approximation day art is kept separate.

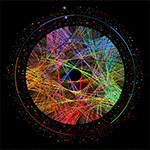

For some time I have been thinking about creating minimalist typographical art based on the digits of `\pi`. The `i`-ness `\pi` project was one of my first forays into this kind of art.

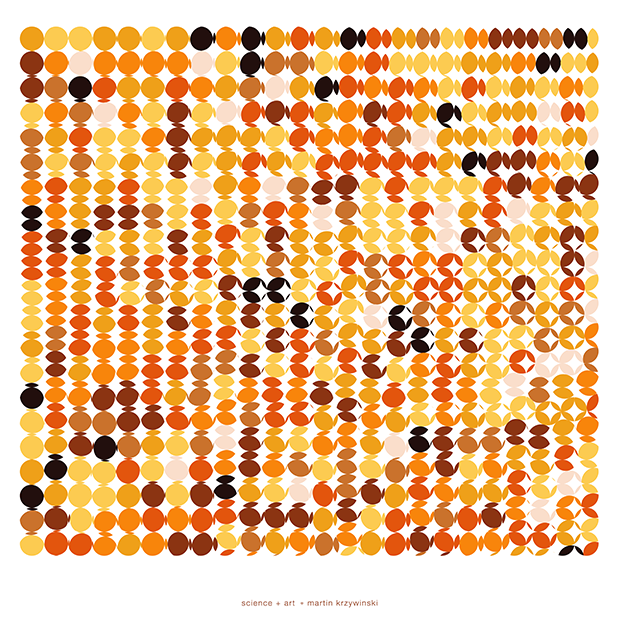

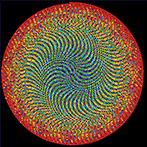

the `i`-ness of `\pi`

In the `i`-ness of `\pi` poster shown above, the average is mapped onto a color and the standard deviation onto size.

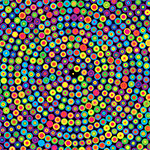

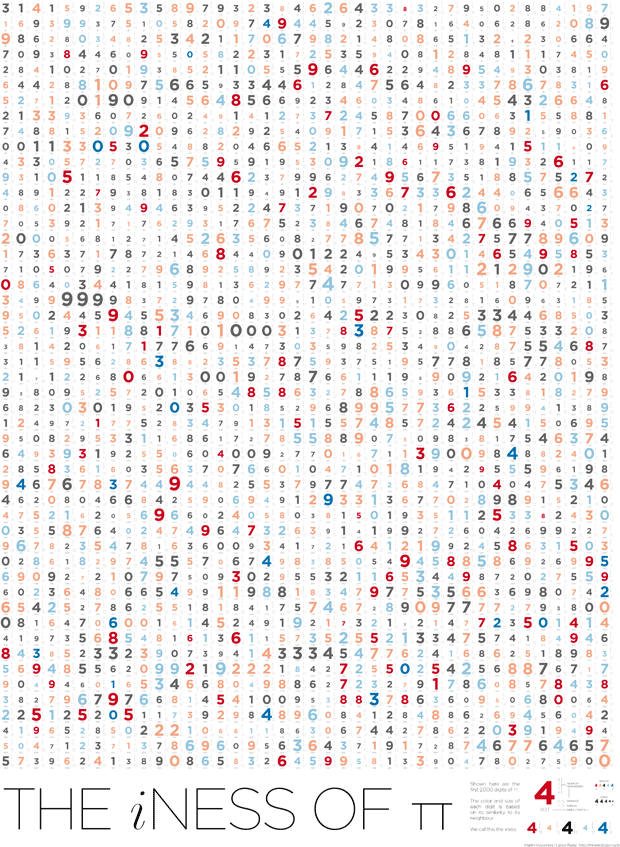

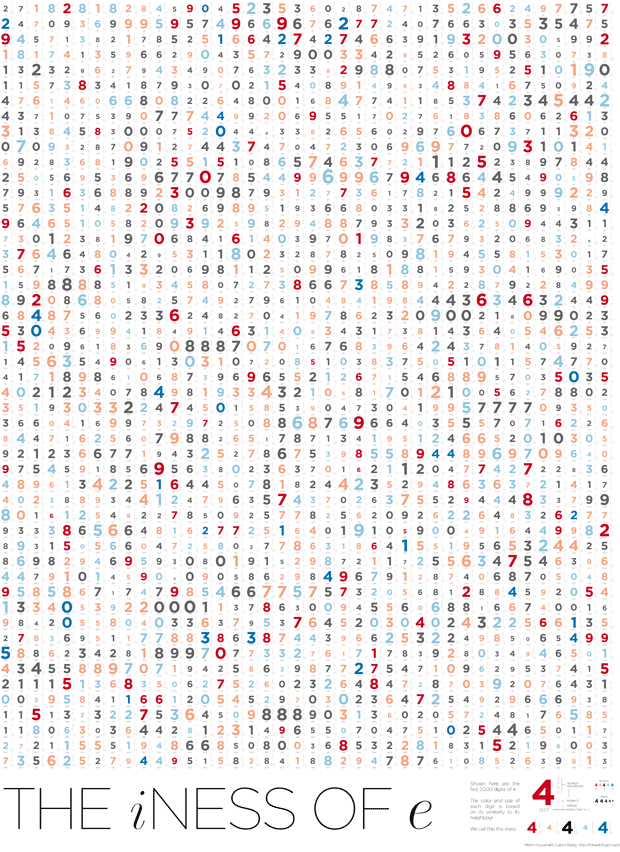

the `i`-ness of `\phi` and `e`

Compare the `i`-ness of `\pi` to that of the other famous transcendental number, `e`, and the mysterious but attractive Golden Ratio, `phi`.

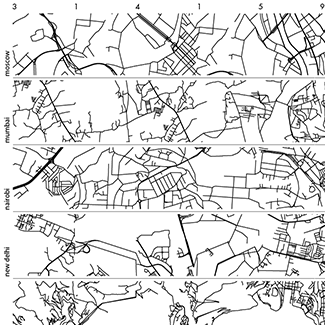

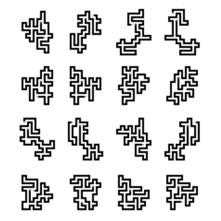

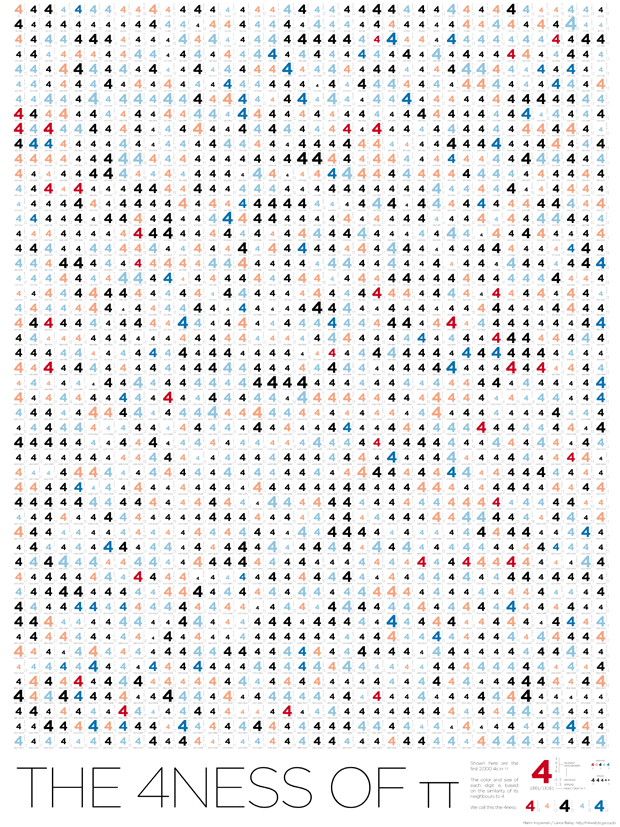

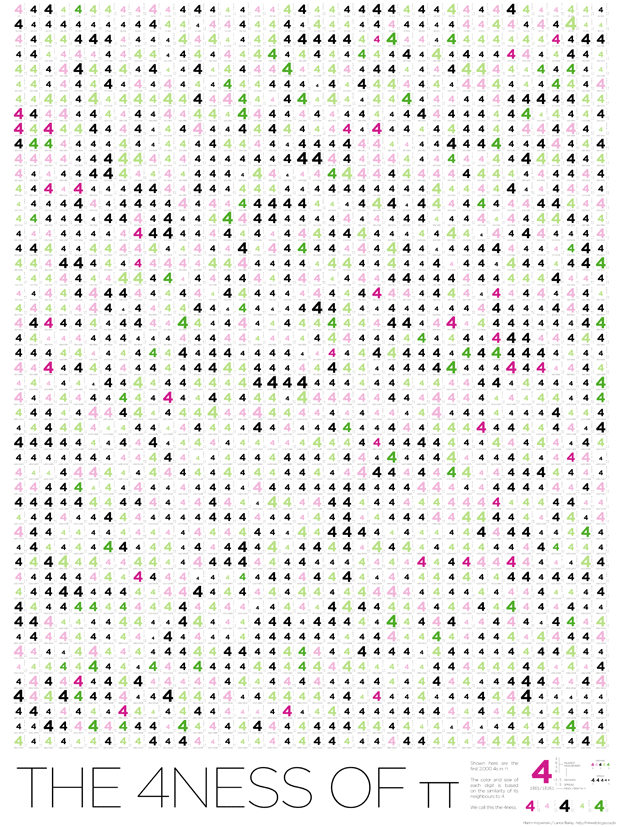

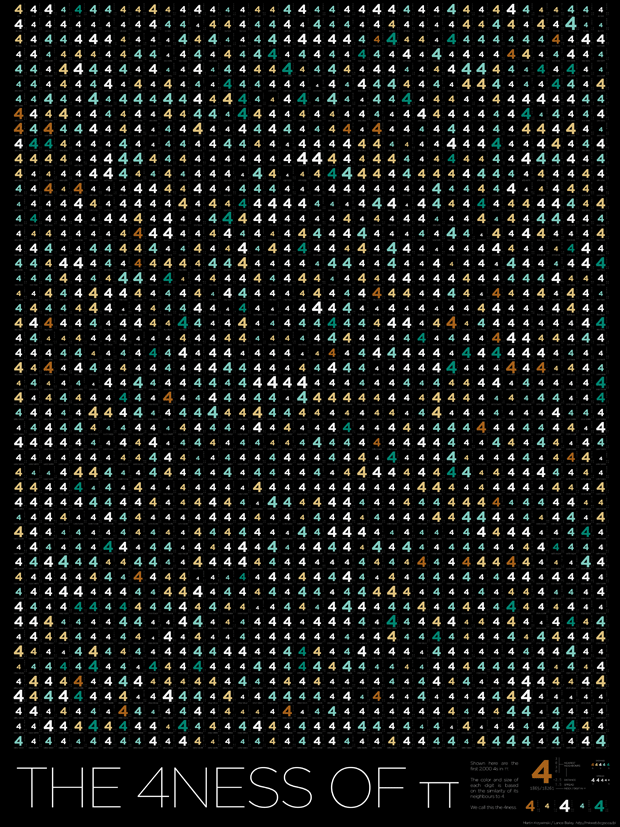

the 4-ness of `\pi`

These posters show the difference between each digit and 4,

Spring and fall color themes of the posters are also available.

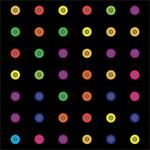

curiously humorous variant

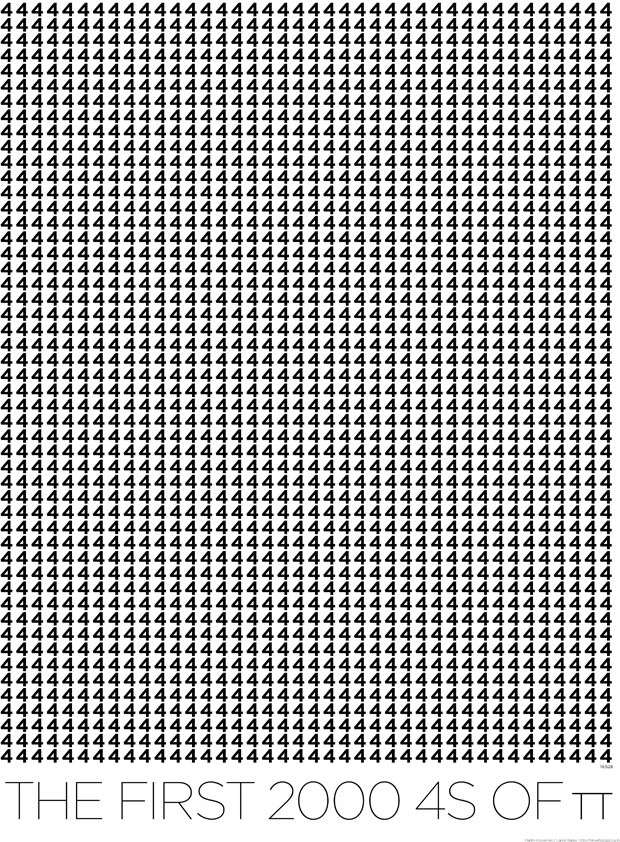

I assure you—`\pi` has a lot of 4s. Why, in the first 19,528 digits there are 2,000 of them! That's a lot. Here they are.

If you stare at them long enough, they even appear to move. Amazing.

Nasa to send our human genome discs to the Moon

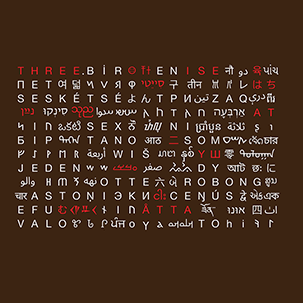

We'd like to say a ‘cosmic hello’: mathematics, culture, palaeontology, art and science, and ... human genomes.

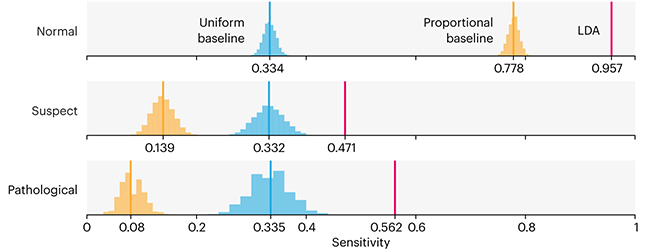

Comparing classifier performance with baselines

All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others. —George Orwell

This month, we will illustrate the importance of establishing a baseline performance level.

Baselines are typically generated independently for each dataset using very simple models. Their role is to set the minimum level of acceptable performance and help with comparing relative improvements in performance of other models.

Unfortunately, baselines are often overlooked and, in the presence of a class imbalance5, must be established with care.

Megahed, F.M, Chen, Y-J., Jones-Farmer, A., Rigdon, S.E., Krzywinski, M. & Altman, N. (2024) Points of significance: Comparing classifier performance with baselines. Nat. Methods 20.

Happy 2024 π Day—

sunflowers ho!

Celebrate π Day (March 14th) and dig into the digit garden. Let's grow something.

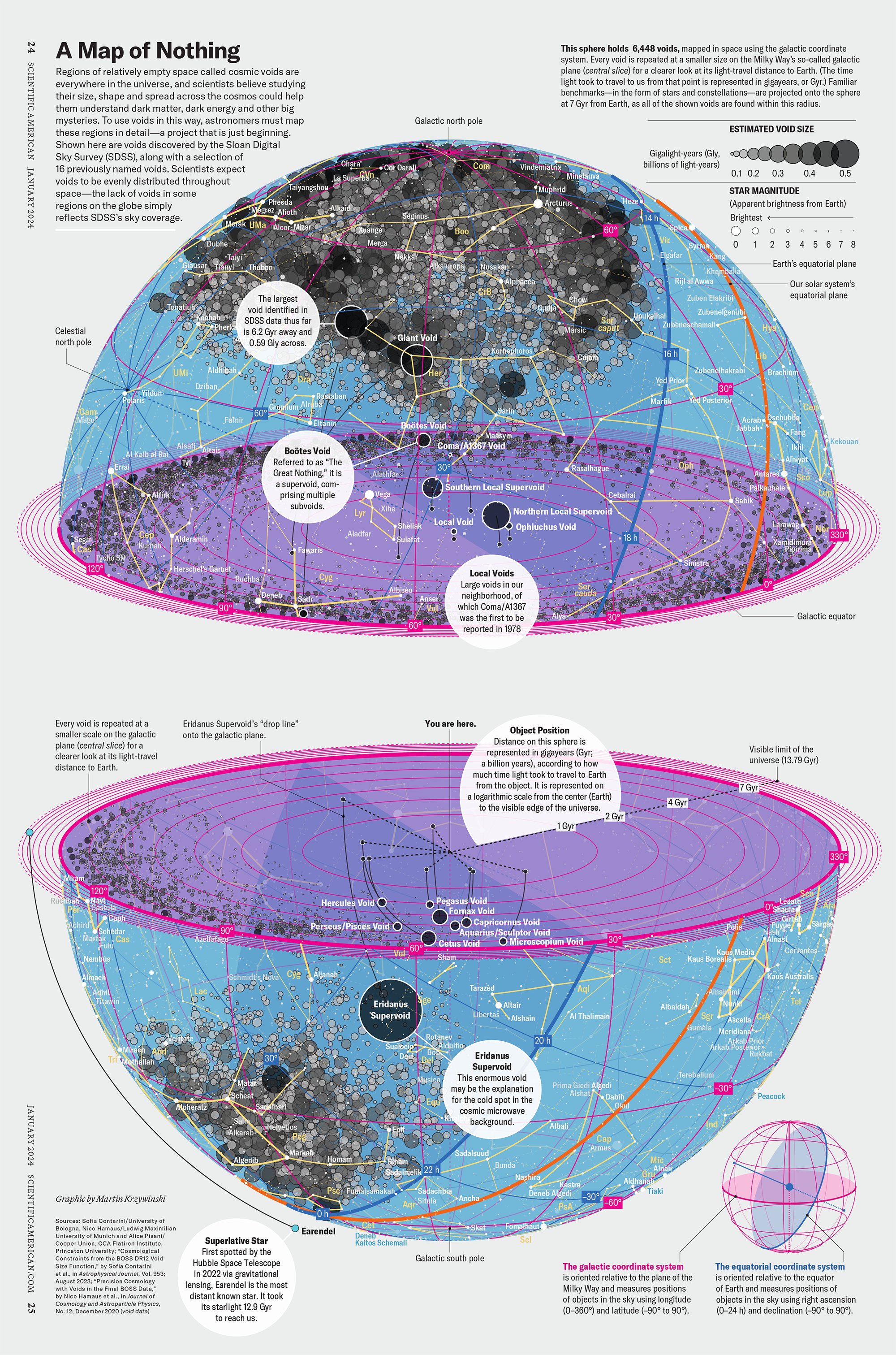

How Analyzing Cosmic Nothing Might Explain Everything

Huge empty areas of the universe called voids could help solve the greatest mysteries in the cosmos.

My graphic accompanying How Analyzing Cosmic Nothing Might Explain Everything in the January 2024 issue of Scientific American depicts the entire Universe in a two-page spread — full of nothing.

The graphic uses the latest data from SDSS 12 and is an update to my Superclusters and Voids poster.

Michael Lemonick (editor) explains on the graphic:

“Regions of relatively empty space called cosmic voids are everywhere in the universe, and scientists believe studying their size, shape and spread across the cosmos could help them understand dark matter, dark energy and other big mysteries.

To use voids in this way, astronomers must map these regions in detail—a project that is just beginning.

Shown here are voids discovered by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS), along with a selection of 16 previously named voids. Scientists expect voids to be evenly distributed throughout space—the lack of voids in some regions on the globe simply reflects SDSS’s sky coverage.”

voids

Sofia Contarini, Alice Pisani, Nico Hamaus, Federico Marulli Lauro Moscardini & Marco Baldi (2023) Cosmological Constraints from the BOSS DR12 Void Size Function Astrophysical Journal 953:46.

Nico Hamaus, Alice Pisani, Jin-Ah Choi, Guilhem Lavaux, Benjamin D. Wandelt & Jochen Weller (2020) Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2020:023.

Sloan Digital Sky Survey Data Release 12

Alan MacRobert (Sky & Telescope), Paulina Rowicka/Martin Krzywinski (revisions & Microscopium)

Hoffleit & Warren Jr. (1991) The Bright Star Catalog, 5th Revised Edition (Preliminary Version).

H0 = 67.4 km/(Mpc·s), Ωm = 0.315, Ωv = 0.685. Planck collaboration Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters (2018).

constellation figures

stars

cosmology

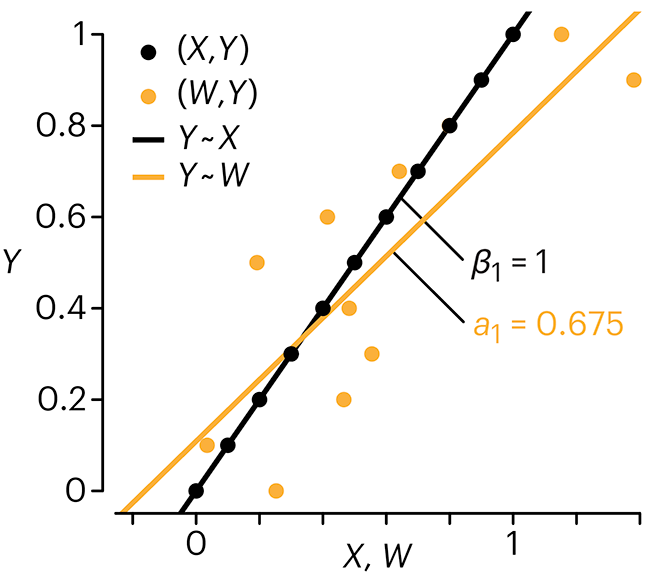

Error in predictor variables

It is the mark of an educated mind to rest satisfied with the degree of precision that the nature of the subject admits and not to seek exactness where only an approximation is possible. —Aristotle

In regression, the predictors are (typically) assumed to have known values that are measured without error.

Practically, however, predictors are often measured with error. This has a profound (but predictable) effect on the estimates of relationships among variables – the so-called “error in variables” problem.

Error in measuring the predictors is often ignored. In this column, we discuss when ignoring this error is harmless and when it can lead to large bias that can leads us to miss important effects.

Altman, N. & Krzywinski, M. (2024) Points of significance: Error in predictor variables. Nat. Methods 20.

Background reading

Altman, N. & Krzywinski, M. (2015) Points of significance: Simple linear regression. Nat. Methods 12:999–1000.

Lever, J., Krzywinski, M. & Altman, N. (2016) Points of significance: Logistic regression. Nat. Methods 13:541–542 (2016).

Das, K., Krzywinski, M. & Altman, N. (2019) Points of significance: Quantile regression. Nat. Methods 16:451–452.

Convolutional neural networks

Nature uses only the longest threads to weave her patterns, so that each small piece of her fabric reveals the organization of the entire tapestry. – Richard Feynman

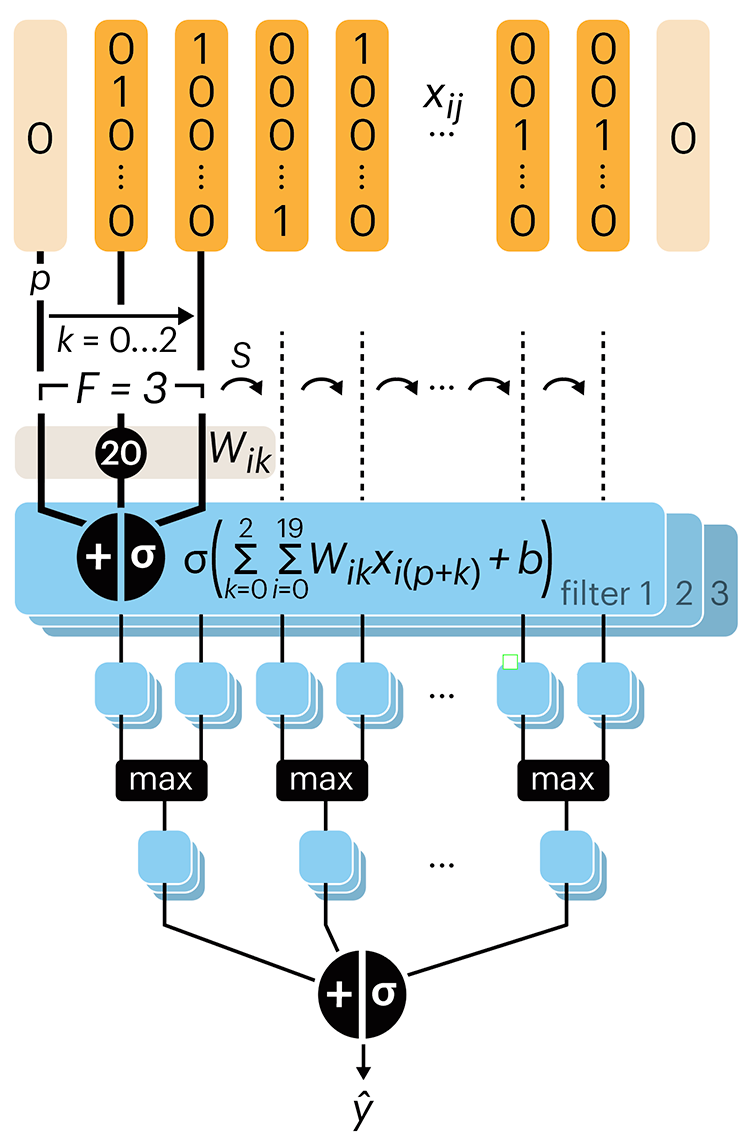

Following up on our Neural network primer column, this month we explore a different kind of network architecture: a convolutional network.

The convolutional network replaces the hidden layer of a fully connected network (FCN) with one or more filters (a kind of neuron that looks at the input within a narrow window).

Even through convolutional networks have far fewer neurons that an FCN, they can perform substantially better for certain kinds of problems, such as sequence motif detection.

Derry, A., Krzywinski, M & Altman, N. (2023) Points of significance: Convolutional neural networks. Nature Methods 20:1269–1270.

Background reading

Derry, A., Krzywinski, M. & Altman, N. (2023) Points of significance: Neural network primer. Nature Methods 20:165–167.

Lever, J., Krzywinski, M. & Altman, N. (2016) Points of significance: Logistic regression. Nature Methods 13:541–542.