Art of the Personalized Oncogenomics Program

A poet is, after all, a sort of scientist, but engaged in a qualitative science in which nothing is measurable. He lives with data that cannot be numbered, and his experiments can be done only once. The information in a poem is, by definition, not reproducible. He becomes an equivalent of scientist, in the act of examining and sorting the things popping in [to his head], finding the marks of remote similarity, points of distant relationship, tiny irregularities that indicate that this one is really the same as that one over there only more important. Gauging the fit, he can meticulously place pieces of the universe together, in geometric configurations that are as beautiful and balanced as crystals.

— Lewis Thomas (The Medusa and the Snail: More Notes of a Biology Watcher)

contents

As individuals, we all have slightly different genomes. If you compare the genomes of two people, you will find about 3 million base pair differences, which is about 0.1% of the genome.

This variation exists not only within the population but potentially also, to a lesser extent, among our cells, which number around 40 trillion. That's roughly 10,000 cells for each base in your 3 billion base genome. And each has a role to play.

| POG cases, by tissue type | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | ||

| Gastrointestinal ● | 141 | 25 | |

| Breast ● | 138 | 25 | |

| Thoracic ● | 57 | 10 | |

| Gynecologic ● | 45 | 8.3 | |

| Soft tissue ● | 44 | 8.1 | |

| Skin ● | 11 | 2.0 | |

| Urologic ● | 8 | 1.5 | |

| Hematologic ● | 7 | 1.3 | |

| Head and neck ● | 6 | 1.1 | |

| Endocrine ● | 5 | 0.9 | |

| Central nervous system ● | 5 | 0.9 | |

| Other ● | 78 | 14 | |

| ALL | 545 | ||

One consequence of this complexity and variation is that changes in the genome (through mutation or other processes) can have very different effects, depending on both the change and the genome. Cancer is a phenomena in which cells' ability to organize themselves as they divide is altered due to changes in the genome. It is an incredibly complex biological phenomenon—considering all the genomes in the population and all the possible changes that may arise, there is truly an inexhaustible number of ways in which the genome can break.

Cancers are classified according to their site of origin, such as lung, breast, liver, or colon. This is a coarse grouping—within each group there are many subtypes with differences in response to treatment and overall behaviour.

The design of the POG art highlights the diversity and similarity among cases. The diversity is what makes the study of cancer difficult and the similarities are what makes inference possible.

Each case is represented by three concentric rings. The width of each ring represents the extent to which the case is similar (as measured by correlation) to cancers of the type encoded by the color of the ring (see Methods).

In additional to the posters, I've created remixes for your desktop at 4k resolution.

This year, the cyclists in the Ride to Conquer Cancer will not only have the chance to raise money for research (as they've always done) but also do so while wearing data (as they've never done before).

You can purchase your own data-powered and human-driven cycling jersey.

Beyond Belief Campaign BRCA Art

Fuelled by philanthropy, findings into the workings of BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes have led to groundbreaking research and lifesaving innovations to care for families facing cancer.

This set of 100 one-of-a-kind prints explore the structure of these genes. Each artwork is unique — if you put them all together, you get the full sequence of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 proteins.

Propensity score weighting

The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few. —Mr. Spock (Star Trek II)

This month, we explore a related and powerful technique to address bias: propensity score weighting (PSW), which applies weights to each subject instead of matching (or discarding) them.

Kurz, C.F., Krzywinski, M. & Altman, N. (2025) Points of significance: Propensity score weighting. Nat. Methods 22:1–3.

Happy 2025 π Day—

TTCAGT: a sequence of digits

Celebrate π Day (March 14th) and sequence digits like its 1999. Let's call some peaks.

Crafting 10 Years of Statistics Explanations: Points of Significance

I don’t have good luck in the match points. —Rafael Nadal, Spanish tennis player

Points of Significance is an ongoing series of short articles about statistics in Nature Methods that started in 2013. Its aim is to provide clear explanations of essential concepts in statistics for a nonspecialist audience. The articles favor heuristic explanations and make extensive use of simulated examples and graphical explanations, while maintaining mathematical rigor.

Topics range from basic, but often misunderstood, such as uncertainty and P-values, to relatively advanced, but often neglected, such as the error-in-variables problem and the curse of dimensionality. More recent articles have focused on timely topics such as modeling of epidemics, machine learning, and neural networks.

In this article, we discuss the evolution of topics and details behind some of the story arcs, our approach to crafting statistical explanations and narratives, and our use of figures and numerical simulations as props for building understanding.

Altman, N. & Krzywinski, M. (2025) Crafting 10 Years of Statistics Explanations: Points of Significance. Annual Review of Statistics and Its Application 12:69–87.

Propensity score matching

I don’t have good luck in the match points. —Rafael Nadal, Spanish tennis player

In many experimental designs, we need to keep in mind the possibility of confounding variables, which may give rise to bias in the estimate of the treatment effect.

If the control and experimental groups aren't matched (or, roughly, similar enough), this bias can arise.

Sometimes this can be dealt with by randomizing, which on average can balance this effect out. When randomization is not possible, propensity score matching is an excellent strategy to match control and experimental groups.

Kurz, C.F., Krzywinski, M. & Altman, N. (2024) Points of significance: Propensity score matching. Nat. Methods 21:1770–1772.

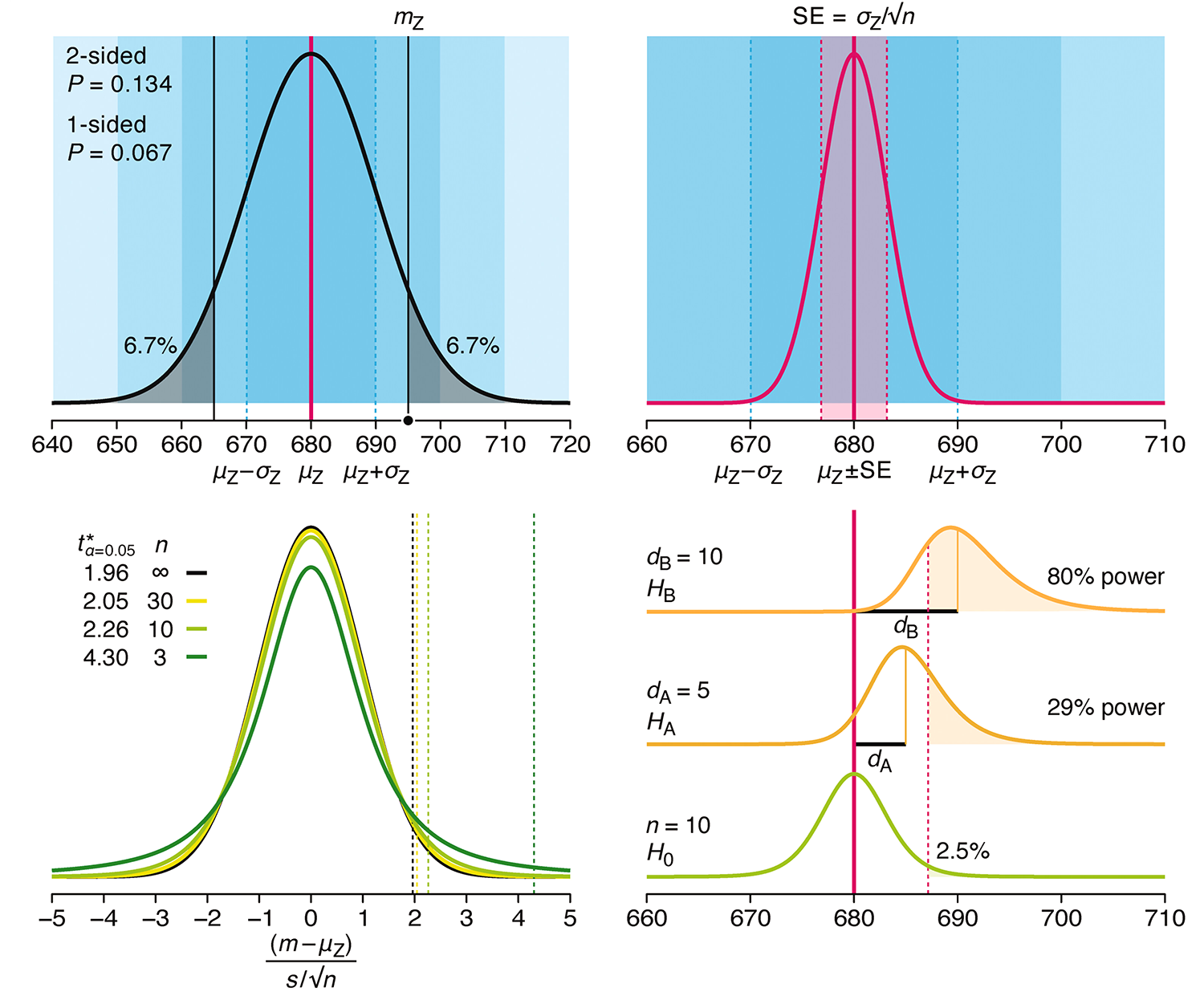

Understanding p-values and significance

P-values combined with estimates of effect size are used to assess the importance of experimental results. However, their interpretation can be invalidated by selection bias when testing multiple hypotheses, fitting multiple models or even informally selecting results that seem interesting after observing the data.

We offer an introduction to principled uses of p-values (targeted at the non-specialist) and identify questionable practices to be avoided.

Altman, N. & Krzywinski, M. (2024) Understanding p-values and significance. Laboratory Animals 58:443–446.