Dummer - Like Nothing Else / A Hummer Satire

The Dummer project might give you the impression that I don't like Hummers. You'd be right.

The project was well received by The New York Times and very poorly by someone who felt sending me hate mail was a good idea. It was — I loved it.

Other Hummer satires include fuh2.com — there's some hope for us all.

The World's Most Popular Questions

What are the world's most popular questions? After all, what we know defines us as much as what we ask. So, let's look at who we are.

Using Google's autocomplete feature, which suggests the most similar searches to the one you have entered, I maintain a real-time compilation of the most common questions asked by millions of worldwide internet users.

This project (a) yields insight into the zeitgeist and (b) scares me. My reason for fright are questions such as these:

General Issues

How do people do extreme couponing?

Why can't I hold all these limes?

Why do I always feel like murdering everyone?

What's up with the World

Is the world really flat?

is the world being controlled by aliens?

Limits & Desires

What happens if I make a formal commitment to Satan?

Love & Heart

Why is my boyfriend so insecure?

Why is my girlfriend so emotional?

Health

My head is full of pretty lumps.

Pain & Suffering

my elbow is dark and dry

why do I continue to hit myself with a hammer?

when does my head stop growing?

Sizes & Extremes

Who is the most powerful Jedi?

Where is the hardest part of your head?

Religion & Faith

Can Jesus microwave a burrito?

Can I pray with my eyes open?

Should I pray for a husband?

Neologisms - New Words, Much Needed

I like words. The pleasure of effectively using acerebral and defenestrate in the same sentence cannot be understated.

On occassion I found myself in a situation where no word fit, existing or that I know about. Instead of rushing to the dictionary, I decided to make up my own, such as inconversible (a statement without a logical converse), mystific (unexplainably wonderful), postpetizer (course ordered after dessert), prenopsis (a summary of something formulated before it was experienced), suscitate (breathe life into, for the first time), and others.

The current list of my neologisms is circos plot, compure, culturally inconversible, dependers, ee spammings, existangsty, fezday, hilbertonian, hive panel, hive plot, inconversible, metaomome, mystific, naytheism, naytheist, nes, neuroterror, neuroterrorism, newgrade, noward, nonposter, oldgrade, omome, omeomics, omicsophy, over, piddle, port knocking, postpetizer, pregratulate, prekfast, prenopsis, prepetizer, quinty, ratio hive, spammings, suscitate, unappropriate .

HDTR: High Dynamic Time Range Photography - Visualizing the Flow of Time

The HDTR method is a new approach to depicting the passage of time. High Dynamic Time Range (HDTR) images and are a composite of many photos taken over a long period of time, such as a day or even longer. Each part of the HDTR image is sampled from a different photo, either by column or row.

For example, the left part of the HDTR image might show the scene from 7am and the very right from 8pm, capturing the variation in light across an entire day.

Propensity score weighting

The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few. —Mr. Spock (Star Trek II)

This month, we explore a related and powerful technique to address bias: propensity score weighting (PSW), which applies weights to each subject instead of matching (or discarding) them.

Kurz, C.F., Krzywinski, M. & Altman, N. (2025) Points of significance: Propensity score weighting. Nat. Methods 22:1–3.

Happy 2025 π Day—

TTCAGT: a sequence of digits

Celebrate π Day (March 14th) and sequence digits like its 1999. Let's call some peaks.

Crafting 10 Years of Statistics Explanations: Points of Significance

I don’t have good luck in the match points. —Rafael Nadal, Spanish tennis player

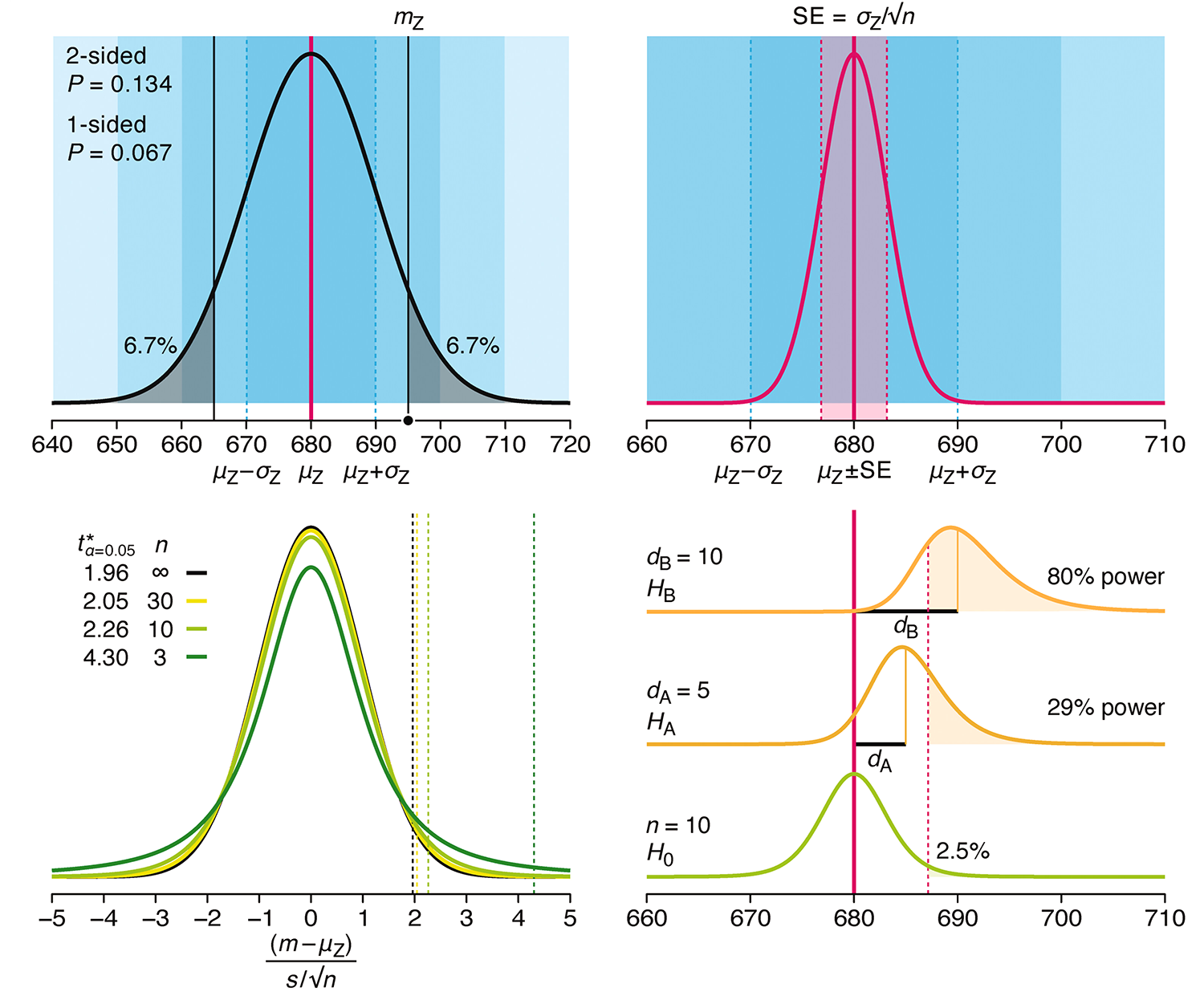

Points of Significance is an ongoing series of short articles about statistics in Nature Methods that started in 2013. Its aim is to provide clear explanations of essential concepts in statistics for a nonspecialist audience. The articles favor heuristic explanations and make extensive use of simulated examples and graphical explanations, while maintaining mathematical rigor.

Topics range from basic, but often misunderstood, such as uncertainty and P-values, to relatively advanced, but often neglected, such as the error-in-variables problem and the curse of dimensionality. More recent articles have focused on timely topics such as modeling of epidemics, machine learning, and neural networks.

In this article, we discuss the evolution of topics and details behind some of the story arcs, our approach to crafting statistical explanations and narratives, and our use of figures and numerical simulations as props for building understanding.

Altman, N. & Krzywinski, M. (2025) Crafting 10 Years of Statistics Explanations: Points of Significance. Annual Review of Statistics and Its Application 12:69–87.

Propensity score matching

I don’t have good luck in the match points. —Rafael Nadal, Spanish tennis player

In many experimental designs, we need to keep in mind the possibility of confounding variables, which may give rise to bias in the estimate of the treatment effect.

If the control and experimental groups aren't matched (or, roughly, similar enough), this bias can arise.

Sometimes this can be dealt with by randomizing, which on average can balance this effect out. When randomization is not possible, propensity score matching is an excellent strategy to match control and experimental groups.

Kurz, C.F., Krzywinski, M. & Altman, N. (2024) Points of significance: Propensity score matching. Nat. Methods 21:1770–1772.

Understanding p-values and significance

P-values combined with estimates of effect size are used to assess the importance of experimental results. However, their interpretation can be invalidated by selection bias when testing multiple hypotheses, fitting multiple models or even informally selecting results that seem interesting after observing the data.

We offer an introduction to principled uses of p-values (targeted at the non-specialist) and identify questionable practices to be avoided.

Altman, N. & Krzywinski, M. (2024) Understanding p-values and significance. Laboratory Animals 58:443–446.

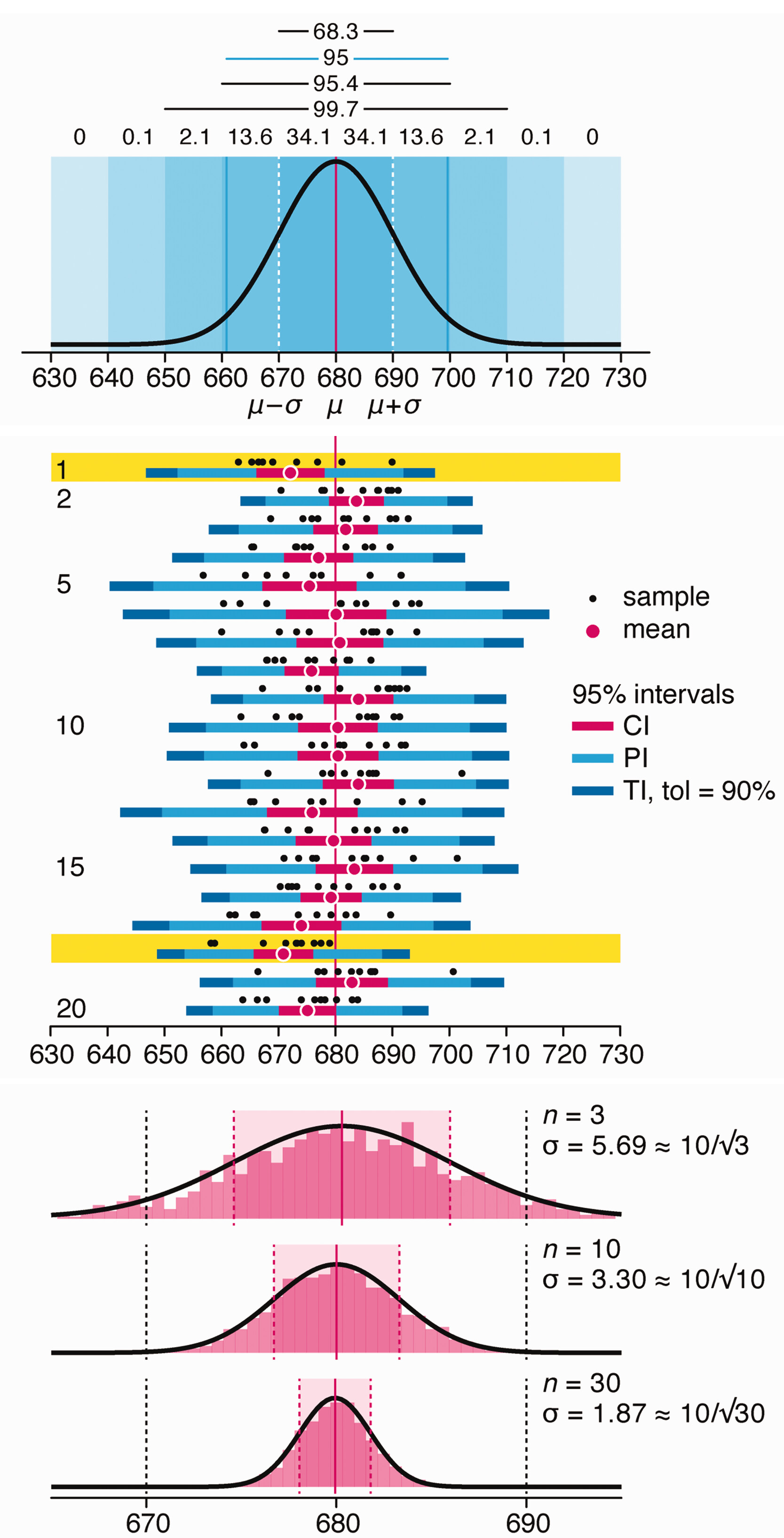

Depicting variability and uncertainty using intervals and error bars

Variability is inherent in most biological systems due to differences among members of the population. Two types of variation are commonly observed in studies: differences among samples and the “error” in estimating a population parameter (e.g. mean) from a sample. While these concepts are fundamentally very different, the associated variation is often expressed using similar notation—an interval that represents a range of values with a lower and upper bound.

In this article we discuss how common intervals are used (and misused).

Altman, N. & Krzywinski, M. (2024) Depicting variability and uncertainty using intervals and error bars. Laboratory Animals 58:453–456.