The trees along this city street,

Save for the traffic and the trains,

Would make a sound as thin and sweet

As trees in country lanes.

And people standing in their shade

Out of a shower, undoubtedly

Would hear such music as is made

Upon a country tree.

Oh, little leaves that are so dumb

Against the shrieking city air,

I watch you when the wind has come,—

I know what sound is there.

— Edna St. Vincent Millay

Nature Biotechnology Cover

11 April 2022, Issue 40, Volume 4

Konno, N. et al. Deep distributed computing to reconstruct extremely large lineage trees (2022) Nature Biotechnology 40:566–575.

The cover design accompanies the paper by Konno et al., which presents a highly efficient distributed computing method for the reconstruction of evolutionary trees from very large datasets.

The cover is a rearrangement of the very large phylogenetic data set depicted in Figure 2a in the paper. You can browse this data set using the HiView server.

The source of inspiration for the cover design came from previous work, where I drew trees from data.

I receive email. One day, I received this one.

I am a Norwegian biology student that has recently become a huge fan of your data art! It's beautiful, really!

What I wanted to ask you, if it's possible for you to help me a little bit on the way of a project I'm starting.

I have had the pleasure of working with a PhD-student here at the university in Bergen, she has taught me so much, and given me a lot of experience in the field, as well as opened up some big career "doors" for me.

She is supposed to deliver her PhD in November and I want to give here a gift to say thank you for all she has done for me.

My idea is this: some sort of visualization of the data she is using in here PhD. She is studying plant communities in Norway, and I have access to the data (plant heights, carbon in the air, thickness of leafs, number of individuals and so on), but i'm not sure how I can make it look beautiful.

So to clarify, I'm not looking for a diagram that is useful or anything, but just pretty to look at, and that is a memory of all the data she has collected, and worked with for the last 4 years. Maybe a diagram in different colors, depending on what the value is, in just a random order... or something...

So do you have any idea of how I can do this? What program do you use when you make your diagrams?

Understand if you dont have the time to answer this, but thank you anyway for reading, and for all you have created!

—Ruben Thormodsæter

I love Norway and I love people that love people who love science.

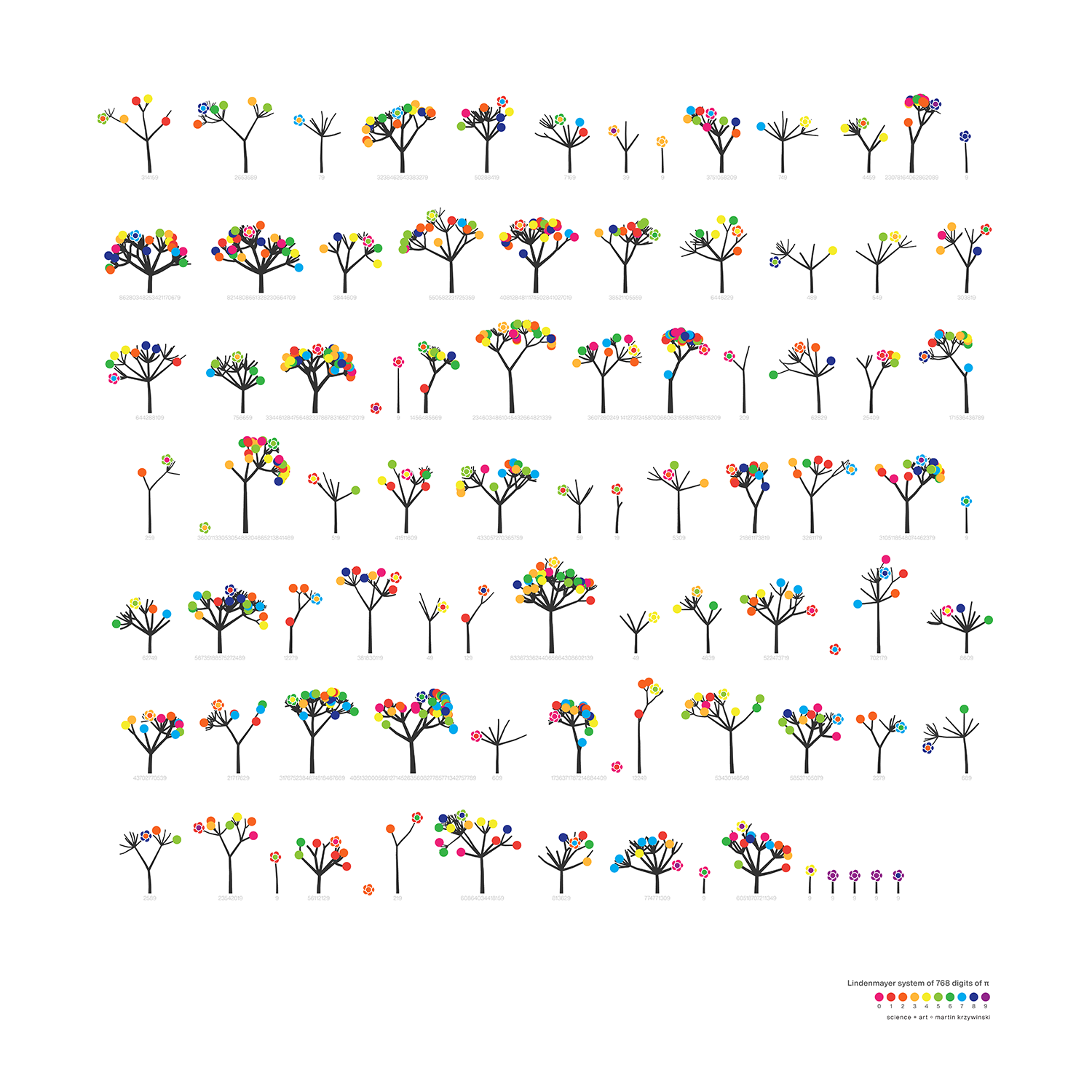

Since the dataset was a list of 376 individual plants, each annotated with species/genus and growth parameters such as height, mass and so on, and Ruben wanted something that is “not ... useful or anything” but rather “pretty to look at” based on “all the data she has collected and worked with for the last 4 years”.

I thought it would be both useful and pretty to represent the plant data by ... growing trees — in silico. One way to do this is to use an L-system.

So, here's the data

id,year,site,genus,species,height,mass,thick,plot,drought,plotmass,green AA86T,2019,Lygra,Erica,tetralix,27,0.02115,0.166,1.3,0,,0.675 AA96C,2019,Lygra,Agrostis,capillaris,9,0.01477,0.107,3.3,90,186.39,0.7025 AA99C,2019,Lygra,Pedicularis,sylvatica,4,0.01806,0.064,2.3,50,80.92,0.695625 AB12C,2019,Lygra,Avenella,flexuosa,6.5,0.03173,0.154,3.3,90,186.39,0.7025 AB17C,2019,Lygra,Carex,pilulifera,10,0.04504,0.154,2.3,50,80.92,0.695625 AB30O,2019,Lygra,Vaccinium,myrtillus,9,0.02605,0.116,2.1,0,111.11,0.636875 ...

and here's the final poster.

I had such a great time with the L-systems that when Pi Day came around, I grew more trees. This time, using the digits of `\pi` to inform branching and sprouting.

So, for 2021 Pi Day, I tried to see the forest through the digits.

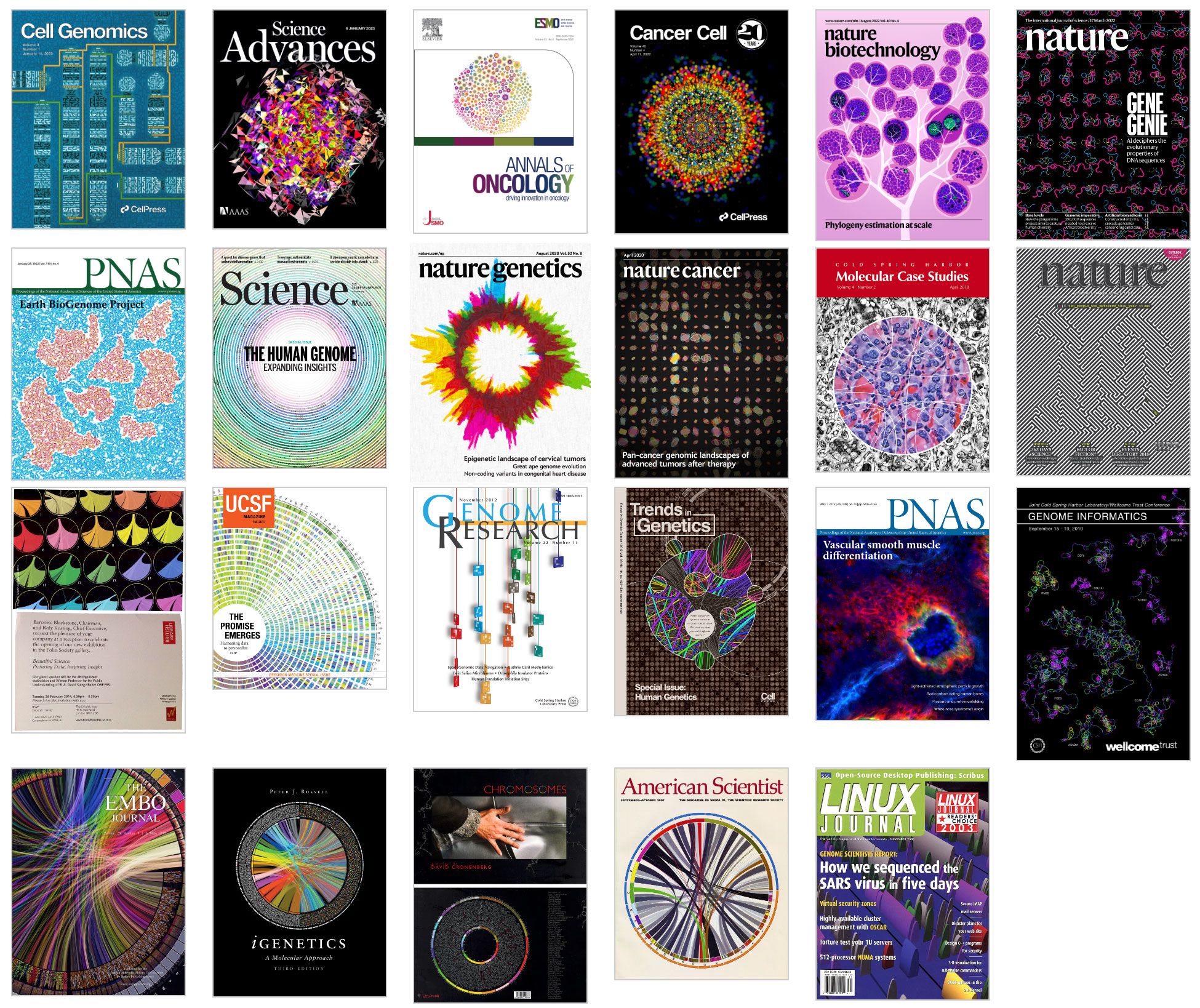

Browse my gallery of cover designs.

Propensity score weighting

The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few. —Mr. Spock (Star Trek II)

This month, we explore a related and powerful technique to address bias: propensity score weighting (PSW), which applies weights to each subject instead of matching (or discarding) them.

Kurz, C.F., Krzywinski, M. & Altman, N. (2025) Points of significance: Propensity score weighting. Nat. Methods 22:1–3.

Happy 2025 π Day—

TTCAGT: a sequence of digits

Celebrate π Day (March 14th) and sequence digits like its 1999. Let's call some peaks.

Crafting 10 Years of Statistics Explanations: Points of Significance

I don’t have good luck in the match points. —Rafael Nadal, Spanish tennis player

Points of Significance is an ongoing series of short articles about statistics in Nature Methods that started in 2013. Its aim is to provide clear explanations of essential concepts in statistics for a nonspecialist audience. The articles favor heuristic explanations and make extensive use of simulated examples and graphical explanations, while maintaining mathematical rigor.

Topics range from basic, but often misunderstood, such as uncertainty and P-values, to relatively advanced, but often neglected, such as the error-in-variables problem and the curse of dimensionality. More recent articles have focused on timely topics such as modeling of epidemics, machine learning, and neural networks.

In this article, we discuss the evolution of topics and details behind some of the story arcs, our approach to crafting statistical explanations and narratives, and our use of figures and numerical simulations as props for building understanding.

Altman, N. & Krzywinski, M. (2025) Crafting 10 Years of Statistics Explanations: Points of Significance. Annual Review of Statistics and Its Application 12:69–87.

Propensity score matching

I don’t have good luck in the match points. —Rafael Nadal, Spanish tennis player

In many experimental designs, we need to keep in mind the possibility of confounding variables, which may give rise to bias in the estimate of the treatment effect.

If the control and experimental groups aren't matched (or, roughly, similar enough), this bias can arise.

Sometimes this can be dealt with by randomizing, which on average can balance this effect out. When randomization is not possible, propensity score matching is an excellent strategy to match control and experimental groups.

Kurz, C.F., Krzywinski, M. & Altman, N. (2024) Points of significance: Propensity score matching. Nat. Methods 21:1770–1772.

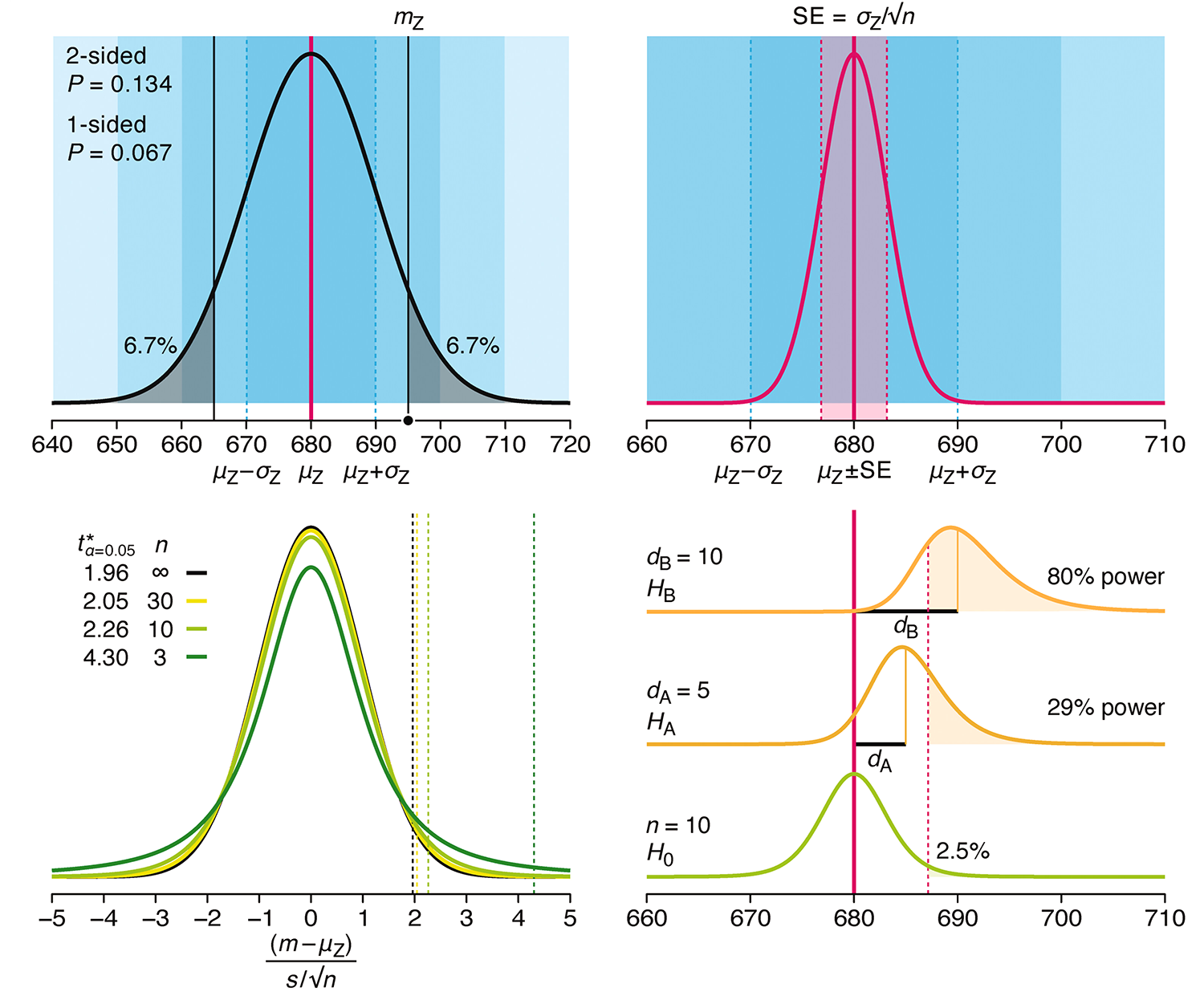

Understanding p-values and significance

P-values combined with estimates of effect size are used to assess the importance of experimental results. However, their interpretation can be invalidated by selection bias when testing multiple hypotheses, fitting multiple models or even informally selecting results that seem interesting after observing the data.

We offer an introduction to principled uses of p-values (targeted at the non-specialist) and identify questionable practices to be avoided.

Altman, N. & Krzywinski, M. (2024) Understanding p-values and significance. Laboratory Animals 58:443–446.