art + science activism

Watch the video of this project, which features the participants who have a BRCA mutation and their interaction with the piece. The video also highlights the design and construction of the mural.

Watch the video of this project, which features the participants who have a BRCA mutation and their interaction with the piece. The video also highlights the design and construction of the mural.

Human Genome Art by Humans with Genomes

I recently took part in a deeply meaningful collaboration of science, art and personal stories of cancer survivors.

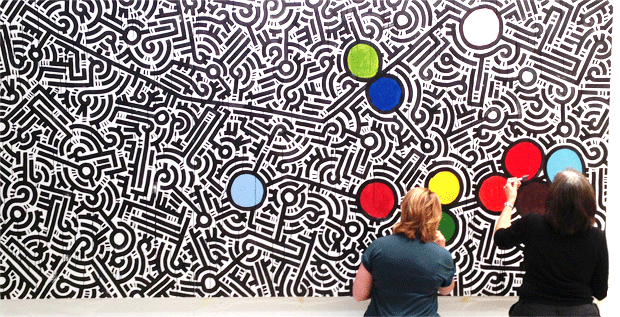

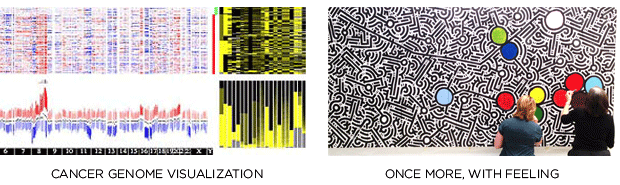

Together with Joanna Rudnick and Aaron De La Cruz, we sought to create a work of art that combines the science of cancer genomics and the individuals whose lives are affected by genetic mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, where genomic changes drastically increase one's chances of breast and ovarian cancer.

We wanted to make something that is scientifically accurate, artistically beautiful and emotionally engaging. The complexity of the genome, the multitudes of other genes and possible mutations and the millions of personal stories of hardship and survival were just a few of the elements we wanted to include the the piece.

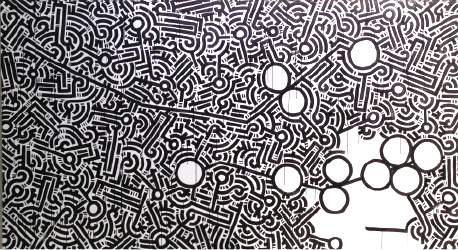

My role was to provide the scientific direction behind the design and incorporate it into the aesthetic of Aaron De La Cruz, a street artist from San Francisco whose work echoes information, complexity, interaction and continuity. We all have a genome — a different genome. The ways in which our genomes are different is what gives us traits like hair and eye color, but is also what makes some of us predisposed to diseases like cancer.

The mural, which includes elements drawn by the cancer survivors, is part of the Free the Data campaign, which is advocating for an open access model of genome mutation databases so that scientists everywhere can analyze it and help women make informed choices about their breast-cancer risk.

The piece Importance of Data Sharing by Nature Methods illustrated the point:

Imagine you are a physician or researcher and seek to get more confirmation on the clinical impact of particular genetic variants. If your search of public databases comes up empty this does not necessarily mean that nothing is known about the mutations in question. Rather, the information may be locked away as a trade secret in a genetic testing company’s proprietary database.

The New York Times article DNA Project Aims to Make Public a Company’s Data on Cancer Genes captures the current state of the situation.

The mural was constructed on location at InVitae in San Francisco.

A video of the project is available.

Beautiful, meaningful and personal

This work will be, as far as I know, the first human annotation of mutations in the human genome by humans whose genomes have the mutations. That's quite a term!

I've always been mindful of the necessity of the mingling of art and science. In my work I tried to add things I felt about the science I thought to create work that combines our objective understanding of the world we live in with the subjective experience of living in it. This project, by far, has been the most keenly felt.

the design

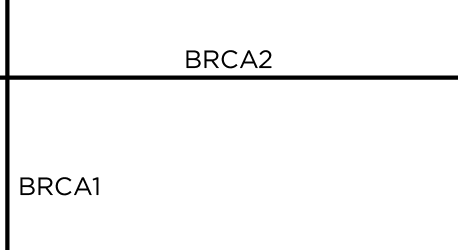

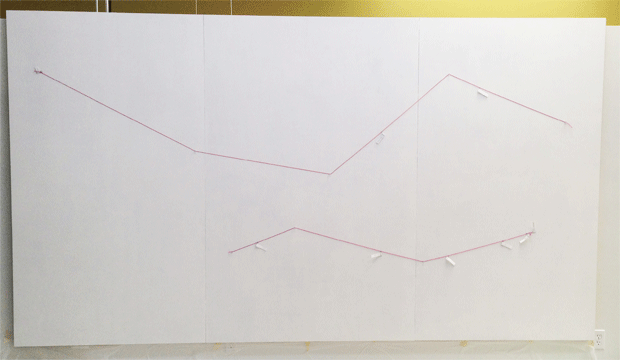

The mural was created in San Francisco on Saturday, July 13th, 2013. We are starting with a 11' x 6' wood canvas. These dimensions reflect the ratio of lengths of BRCA1 and BRCA2 proteins (1,863 and 3,418 amino acids, respectively)

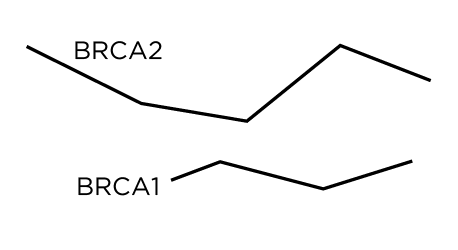

The BRCA1 and BRCA2 proteins are drawn on the canvas as straight-line sections.

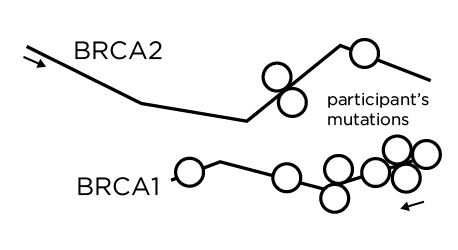

The locations of the participants mutations are positioned on the protein lines as circles. For individuals with large deletions, the circle is placed at the first affected amino acid. Because BRCA1 is location on the opposite strand (anti-sense), its start on the canvas is on the right.

The rest of the genome is now drawn. Aaron's style is perfect for depicting information and the endless complexity of the genome and its interacting elements. We were careful to include elements that indicate that the story told today is not complete. Millions of others have mutations in thousands of other genes, each potentially life-threatening. Just as the stories of our participants will continue to evolve, other stories are waiting to be told.

Once the "reference" genome is depicted, participants with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations will complete the art work by individually marking the positions of their mutations on the art using personalized colors. With Aaron's help, everyone created their own color by mixing primary colors.

From base pair, to genome, to person, to life. All it takes is one tiny change in the genome to change a life forever.

creation of free the data mural

The BRCA1 and BRCA2 lines were placed on the canvas by first pinning two pieces of string, marked with the positions of the mutations.

After drawing the protein lines, it was time to fill the canvas.

Over the next 4 hours, Aaron filled in the canvas with the "rest" of the genome.

Participants

Lucy, Karen, Steve, Ghecemy, Joanna, Jill, Lisa, Lynn, Ruth, Jenica, Susan

Cancer previvors and survivors who have been diagnosed with a mutation on BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes.

Joanna Rudnick (director/producer)

Joanna made her directorial debut with the Emmy-nominated In the Family, a deeply personal film about coming to terms with testing positive for the breast cancer gene BRCA1 mutation and following the storylines of other women and families facing the same hard choices. In the Family premiered at Silverdocs in 2008, was broadcast nationally on PBS P.O.V. the same year and was a finalist for the NIHCM Foundation’s Health Care Radio and Television Journalism Award.

Joanna received a master’s degree in Science and Environmental Journalism from New York University and a bachelor’s degree in English from Northwestern University. Joanna loves the opportunity to teach and mentor and served as an adjunct professor at Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism in the past.

She has written for several publications including Audubon Magazine, The Artful Mind, The Berkshire Record and Humanities. Before finding her way to the wonderful world of documentaries, Joanna served as an Americorps volunteer, implementing project-based environmental curricula in the San Francisco Public School System.

Joanna is one of the cancer survivors whose mutations are encoded in the art.

http://kartemquin.com/about/joanna-rudnick

Aaron De La Cruz (artist)

Aaron De La Cruz's work, though minimal and direct at first, tends to overcome barriers of separation and freely steps in and out of the realms of design, graffiti, and illustration.

The parameters he has chosen to work within actually allow him to free himself and react to the very limitations he has created. This overriding structure and the lack of deliberation while moving within creates a tension when encountering his work due to the almost computer generated grid like systems he creates by unplanned markmaking. The act and the marks themselves are very primal in nature but tend to take on distinct and sometimes higher meanings in the broad range of mediums and contexts they appear in and on.

His work finds strengths in the reduction of his interests in life to minimal information. De La Cruz gains from the idea of exclusion, just because you don't literally see it doesn't mean that its not there.

Nasa to send our human genome discs to the Moon

We'd like to say a ‘cosmic hello’: mathematics, culture, palaeontology, art and science, and ... human genomes.

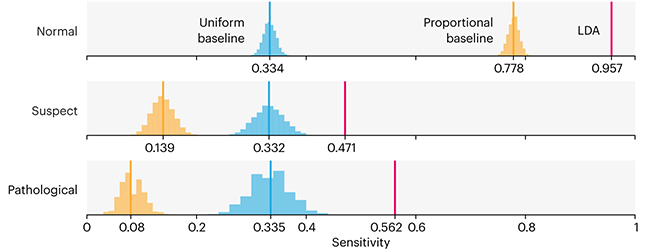

Comparing classifier performance with baselines

All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others. —George Orwell

This month, we will illustrate the importance of establishing a baseline performance level.

Baselines are typically generated independently for each dataset using very simple models. Their role is to set the minimum level of acceptable performance and help with comparing relative improvements in performance of other models.

Unfortunately, baselines are often overlooked and, in the presence of a class imbalance5, must be established with care.

Megahed, F.M, Chen, Y-J., Jones-Farmer, A., Rigdon, S.E., Krzywinski, M. & Altman, N. (2024) Points of significance: Comparing classifier performance with baselines. Nat. Methods 20.

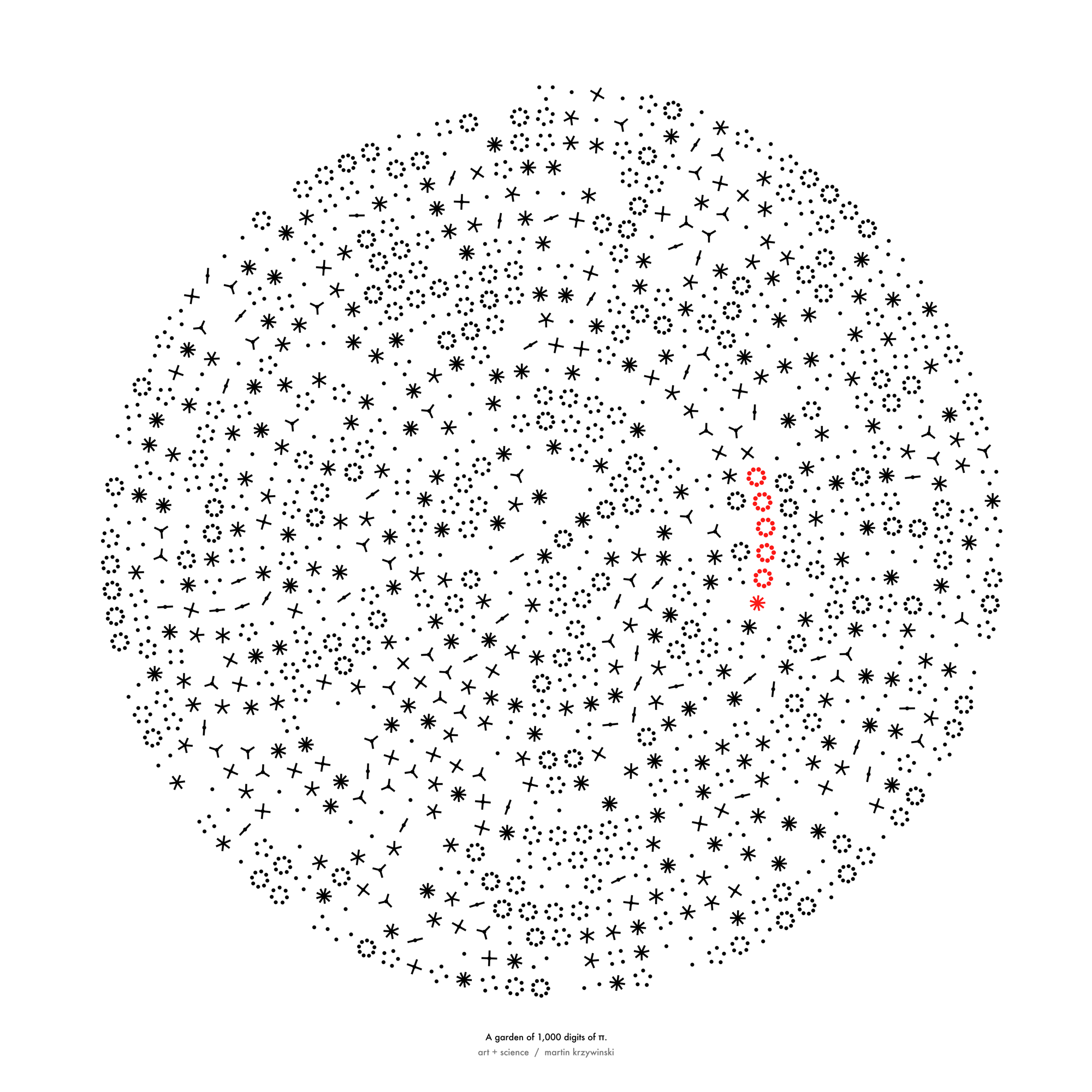

Happy 2024 π Day—

sunflowers ho!

Celebrate π Day (March 14th) and dig into the digit garden. Let's grow something.

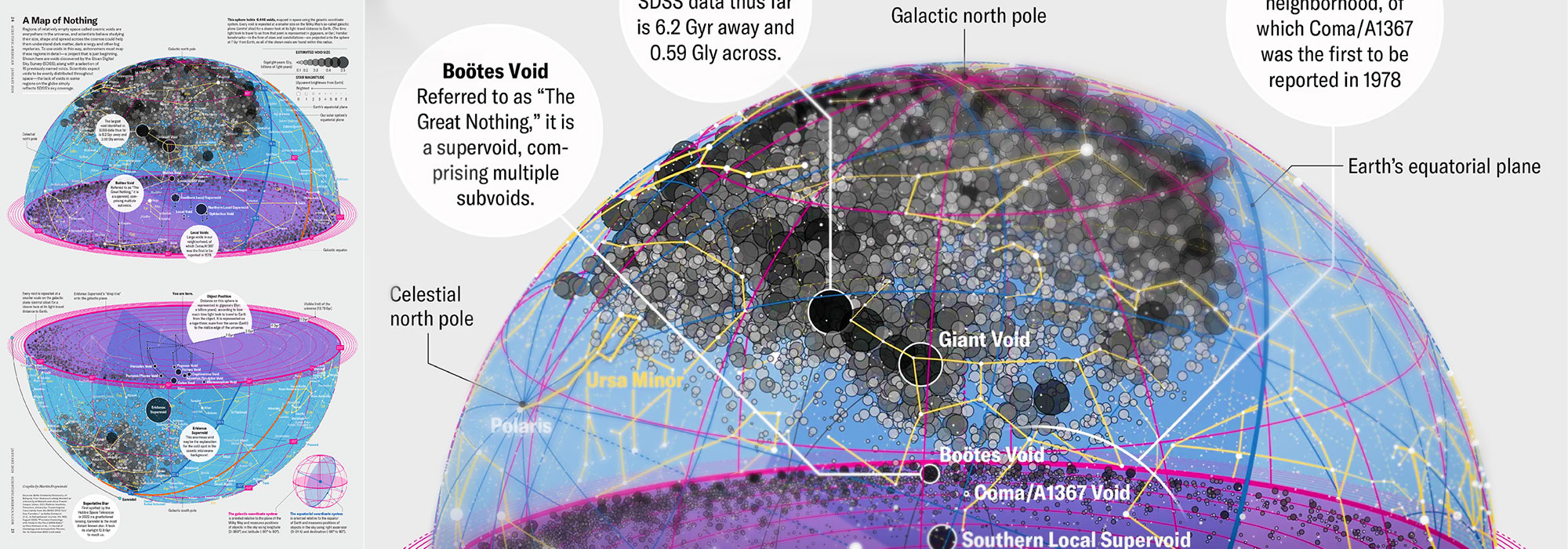

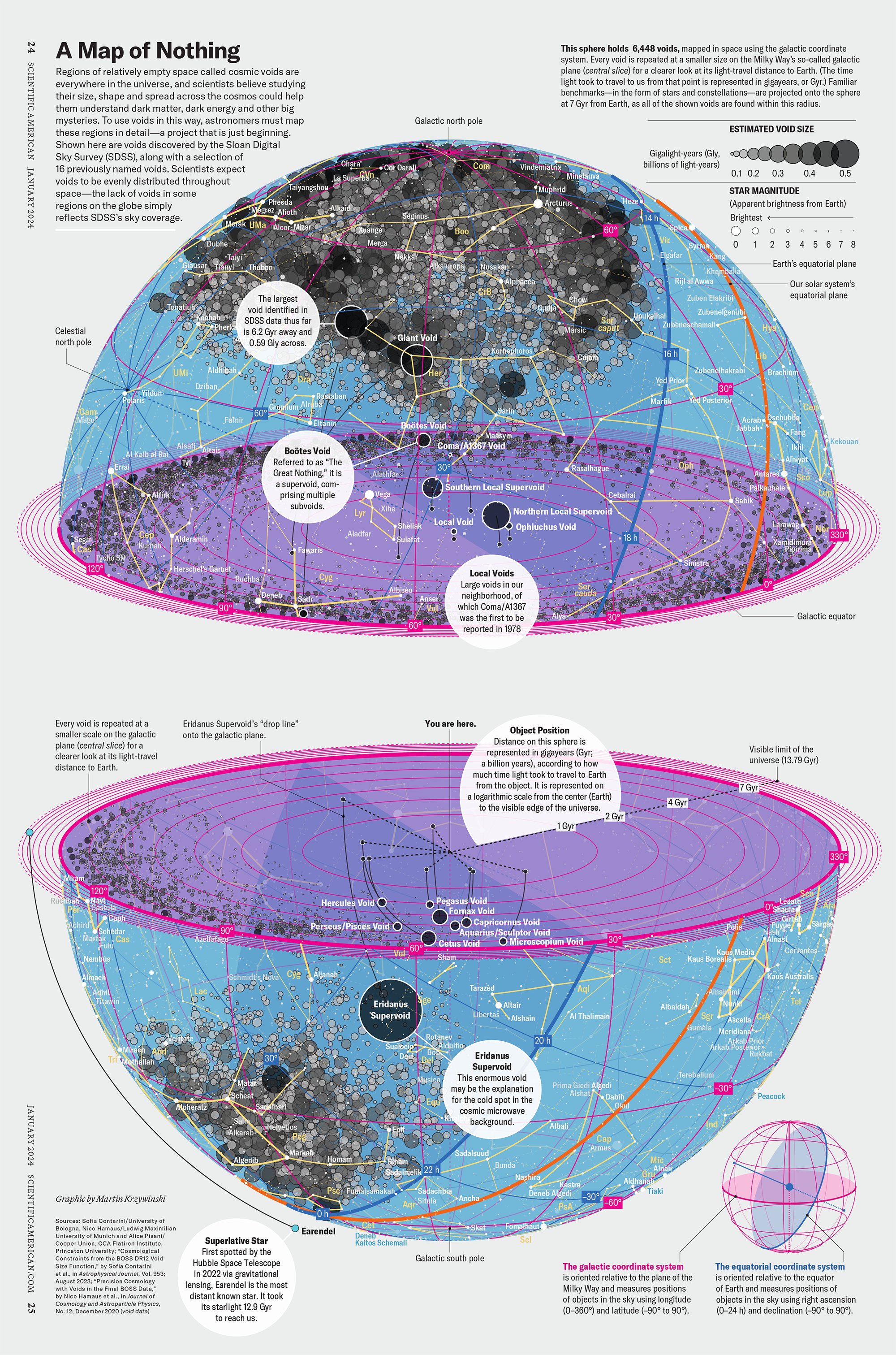

How Analyzing Cosmic Nothing Might Explain Everything

Huge empty areas of the universe called voids could help solve the greatest mysteries in the cosmos.

My graphic accompanying How Analyzing Cosmic Nothing Might Explain Everything in the January 2024 issue of Scientific American depicts the entire Universe in a two-page spread — full of nothing.

The graphic uses the latest data from SDSS 12 and is an update to my Superclusters and Voids poster.

Michael Lemonick (editor) explains on the graphic:

“Regions of relatively empty space called cosmic voids are everywhere in the universe, and scientists believe studying their size, shape and spread across the cosmos could help them understand dark matter, dark energy and other big mysteries.

To use voids in this way, astronomers must map these regions in detail—a project that is just beginning.

Shown here are voids discovered by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS), along with a selection of 16 previously named voids. Scientists expect voids to be evenly distributed throughout space—the lack of voids in some regions on the globe simply reflects SDSS’s sky coverage.”

voids

Sofia Contarini, Alice Pisani, Nico Hamaus, Federico Marulli Lauro Moscardini & Marco Baldi (2023) Cosmological Constraints from the BOSS DR12 Void Size Function Astrophysical Journal 953:46.

Nico Hamaus, Alice Pisani, Jin-Ah Choi, Guilhem Lavaux, Benjamin D. Wandelt & Jochen Weller (2020) Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2020:023.

Sloan Digital Sky Survey Data Release 12

Alan MacRobert (Sky & Telescope), Paulina Rowicka/Martin Krzywinski (revisions & Microscopium)

Hoffleit & Warren Jr. (1991) The Bright Star Catalog, 5th Revised Edition (Preliminary Version).

H0 = 67.4 km/(Mpc·s), Ωm = 0.315, Ωv = 0.685. Planck collaboration Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters (2018).

constellation figures

stars

cosmology

Error in predictor variables

It is the mark of an educated mind to rest satisfied with the degree of precision that the nature of the subject admits and not to seek exactness where only an approximation is possible. —Aristotle

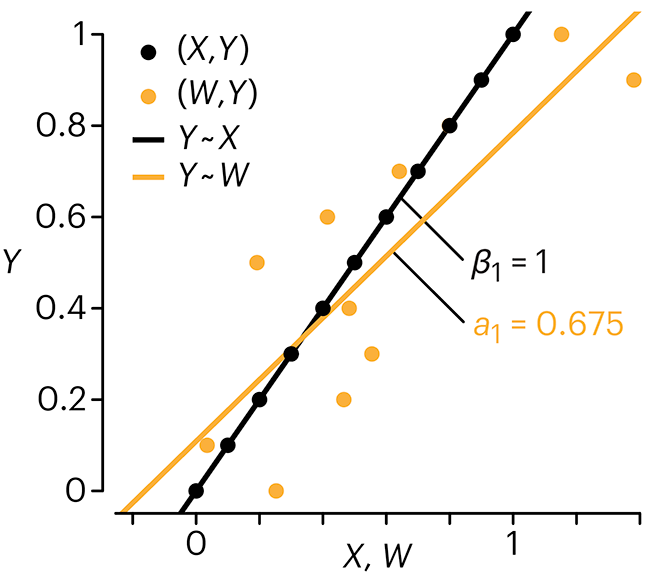

In regression, the predictors are (typically) assumed to have known values that are measured without error.

Practically, however, predictors are often measured with error. This has a profound (but predictable) effect on the estimates of relationships among variables – the so-called “error in variables” problem.

Error in measuring the predictors is often ignored. In this column, we discuss when ignoring this error is harmless and when it can lead to large bias that can leads us to miss important effects.

Altman, N. & Krzywinski, M. (2024) Points of significance: Error in predictor variables. Nat. Methods 20.

Background reading

Altman, N. & Krzywinski, M. (2015) Points of significance: Simple linear regression. Nat. Methods 12:999–1000.

Lever, J., Krzywinski, M. & Altman, N. (2016) Points of significance: Logistic regression. Nat. Methods 13:541–542 (2016).

Das, K., Krzywinski, M. & Altman, N. (2019) Points of significance: Quantile regression. Nat. Methods 16:451–452.